MR images can show the growth of white-matter lesions in the brains of older people as early as 10 years before the onset of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), according to a study by Oregon researchers.

The group from Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) found an average annual increase of 6.5% in white-matter lesions among subjects older than 65 years of age. Accumulation of white-matter lesions increased by an additional 3.3% 10.6 years before the onset of MCI, bringing the total acceleration to 9.8% at that time.

"That [increased accumulation] is an early marker in terms of what that might tell us about the disease and what is happening before clinical symptoms of mild cognitive impairment," lead study author Dr. Lisa Silbert, assistant professor in the department of neurology, told AuntMinnie.com. She presented the study at the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) annual meeting.

By monitoring white-matter changes in the brain, healthcare providers may better determine people at risk for cognitive impairment and plan treatment strategies and disease-specific therapies prior to the onset of dementia.

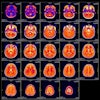

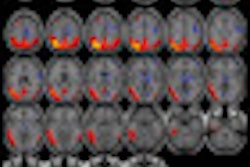

White-matter hyperintensities

Previous studies have shown that the white-matter lesions can have a detrimental effect on cognitive and motor function in the elderly. As the lesions accumulate over time, there is an increased risk of developing MCI, which, in turn, can advance to dementia or Alzheimer's disease.

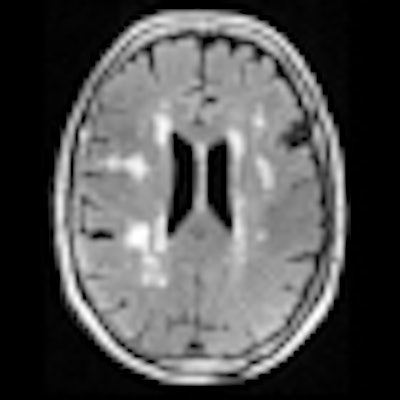

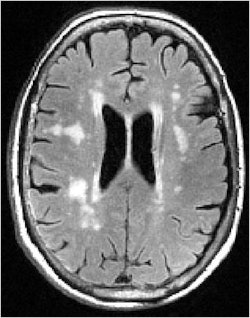

White-matter hyperintensities are commonly seen on MRI of elderly subjects. Image courtesy of Dr. Lisa Silbert.

White-matter hyperintensities are commonly seen on MRI of elderly subjects. Image courtesy of Dr. Lisa Silbert.

"With older individuals, we very commonly see these lesions," Silbert said. "They are often called white-matter hyperintensities because they are bright on certain MR images. These white-matter lesions can affect how we think, walk, and move as we grow older."

Silbert and colleagues analyzed 181 subjects from the Oregon Brain Aging Study (OBAS), which began to recruit people who were at least 65 years of age when the study began in 1989. Individuals in OBAS received yearly evaluations, including brain MRI scans and cognitive and psychological testing.

The researchers used 1.5-tesla MRI, which was considered state-of-the-art in 1989 when OBAS began. To maintain consistency, the study participants continued to receive 1.5-tesla MRI exams during follow-up to measure white-matter hyperintensities and total brain volume.

OBAS patients were followed until they were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, with a follow-up duration of 22.2 years. "Of 181 OBAS subjects followed, 134 [74%] converted to mild cognitive impairment during the follow-up period," Silbert said.

The annual MRI evaluations showed a 6.5% annual rate of increase in white-matter hyperintensities in the early years of the study, according to Silbert and colleagues. White-matter hyperintensity volume increased an additional 3.3% 10.6 years prior to the onset of mild cognitive impairment.

The researchers also found that changes in total brain volume and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurred much closer to MCI symptom onset. An increase in CSF volume occurred 3.7 years before the onset of MCI, while total brain volume decreased five years prior to symptoms of MCI.

Cerebrovascular influence

A total of 90 individuals died during the follow-up period. Of the 63 individuals who converted to mild cognitive impairment and underwent autopsy, 18 (29%) were found to have Alzheimer's as the sole cause of their dementia. Almost the same number of subjects had both Alzheimer's and significant ischemic cerebrovascular disease.

"What this means is still not entirely clear, but the general thought on white-matter changes is that it is due to cerebrovascular disease ... [and] there is significance to the presence of cerebrovascular disease and dementia in the elderly," Silbert said. "Many of them had significant Alzheimer's pathology, but what might be actually driving clinical dementia may be due to the coexistence of vascular disease."

That finding, she added, can have important implications for targeting treatment for these individuals. If a therapy is not successful, it may be due to other pathologies within the patient, she said.

The research was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the Storms Family Fund at the Oregon Community Foundation, and the T&J Meyer Foundation.