Women who undergo routine breast screening wouldn't mind getting the results right away, but not if they have to pay an extra fee for it. Researchers from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston reached that conclusion after surveying 120 women on the cost of immediate mammography reporting.

"Our community has experienced a patient- and market-driven trend to provide immediate interpretation of all screening mammograms and to perform any additional work-up at the same visit. However, the cost of providing immediate screening results and work-up have not been formally assessed," wrote lead author Dr. Sughra Raza in the latest issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology (September 2001, Vol.177:3, pp. 579-583).

With this study, the group sought to answer three main questions: Do patients prefer to receive immediate screening results? Are they willing to pay for it? And what are the potential costs of this service for the hospital and the radiologist?

The anonymous survey was completed by 120 women, ages 35-70. The researchers asked participants to choose between two reporting systems: delayed reporting, where the mammogram was interpreted later and results were sent by mail, and immediate reporting, which included a session with the radiologist and any work-up if necessary.

"Patients were also asked whether they would be willing to wait an additional 30-60 minutes to obtain immediate results, and how much they were willing to pay for this service, with choices [ranging from $0 to $50]," the authors wrote.

According to the results, 67% of the women surveyed said they preferred immediate reporting. Of these 80 women, 78% said they would wait up to an hour for those results. However, only 35% were willing to pay a fee of $25 or less for a quick turnaround.

"We were surprised that only 67% of the women indicated they preferred immediate reporting," Raza said. "We expected this number to be much higher because we are hearing from our patients and our referring physicians that they want to know the results right away. [But] there was still a substantial number of women who are willing to wait for their results."

In terms of cost, Raza and co-authors found that the total additional cost of immediate interpretation at their institution would be $338,640 annually for a volume of 12,000 screening mammograms per year. The cost of each individual screening increased depending on how long the radiologist spent with the patient, from about $29 if the mammographer took 2 minutes to discuss normal results, up to $46 for a 10 minute on-site talk. A hospital may incur additional costs if new staff or equipment is required to produce immediate results.

Finally, "interpreting screening mammograms immediately also incurs indirect costs in two ways: the loss of reimbursement for the initial screening mammogram and subsequent diagnostic mammogram performed another day [reimbursement is now only for a bilateral diagnostic mammogram]," the authors determined. Beyond the financial burden, one serious drawback of immediate reporting is the disruption of workflow, which could result in an increased number of misinterpretations, they added.

In a second mammography study in AJR, researchers focused on the issue of missed cancers during routine screening. For this community-based study, which was lead by Dr. Bonnie Yankaskas from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a series of screening mammograms from routine practice were reassessed by radiologists to pinpoint the percentage of false-negative findings that may have been detectable.

"The general public does not always understand the limitations of screening, particularly that negative findings on a mammogram do not always rule out breast cancer…establishing a community standard for usual experience with missed cancers from community-based screening might be helpful in defense of some screening malpractice cases," the authors stated (AJR, September 2001, Vol.177:3, pp. 535-541).

Using cases from the Carolina Mammography Registry acquired in 1997 and 1998, four radiologists assessed the films of 339 asymptomatic women. A screening mammogram was considered false-negative if the initial diagnosis was negative, but cancer was found within the following year.

Of the four reviewers, two were dedicated mammographers while two were general radiologists whose practices included a significant proportion of breast screening. The reviews were performed in one day with the standard two views.

The four radiologists recommended additional work-up in false-negative breasts an average of 42% of the time. At least three of the four reviewers suggested work-up for 32% of false-negative breasts and 4% of true-negative breasts.

"The difference, 28%, is nearly identical to the estimated detectable missed-cancer rate of 29%," the authors wrote. "The message is that an estimated 71% of missed cancers remain undetectable when interpreted independently by experienced peers."

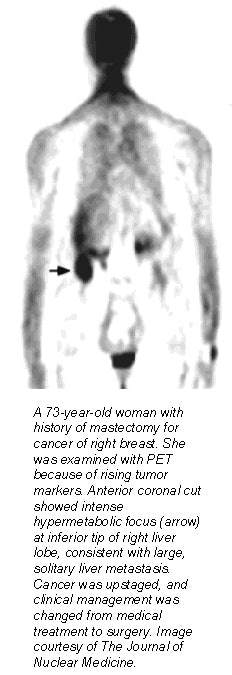

In PET imaging, a study in the latest issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine gauged how referring physicians view the results of whole-body 18F-FDG PET for managing breast cancer patients.

The group from the Ahmanson Biological Imaging Center/Nuclear Medicine Clinic at UCLA in Los Angeles, and the Northern California PET Imaging Center in Sacramento, sent pre- and post-PET questionnaires to the referring physicians of 160 breast cancer patients. All of the patients underwent whole-body 18F-FDG PET scans at either UCLA or the Sacramento facility.

The pre-PET survey asked physicians to specify the clinical stage of each patient and to state the intended management plan before the PET scan. The post-PET portion asked if the exam had brought about any changes in cancer stage and patient management (JNM, September 2001, Vol.42:9, pp. 1334-1337).

|

The authors reported a 31% response rate to their questions, with medical oncologists making up 63% of the respondents. The results of the PET scan changed the clinical stage in 36% of the patients, with 28% upstaged and 4% downstaged.

Information from PET resulted in intermodality management changes for 28% (e.g. from surgery to radiation therapy); intramodality changes for 30% (for example, from one chemotherapeutic agent to another); and no change in 26% of the cases.

In addition, PET uncovered unknown lymph node metastases and unknown distant metastases in 20% of the entire study population, the authors reported. Finally, before the PET exam, 36% of the cancers were classified as stage IV. After the PET exam, 52% were upstaged to stage IV.

By Shalmali PalAuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 6, 2001

Related Reading

Mobile mammographers remember their mission, August 23, 2001

Distance from home influences use of free mammography services, April 4, 2001

FDG-PET gains favor among referring doctors for cancer staging, treatment, June 7, 2000

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com