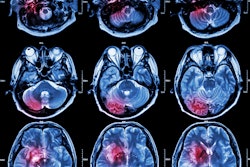

Is playing tackle football linked to changes in brain surface structure and functional alterations in adolescents? It appears so, according to research published February 1 in JAMA Network Open.

The findings underscore the importance of further research on how adolescent athletes are affected by head impacts, wrote a team led by Taylor Zuidema of Indiana University School of Public Health in Bloomington.

"[Our] data support the use of these imaging parameters in a future longitudinal study to gauge the subtle yet cumulative changes in brain structure and neurophysiological effects due to repetitive head impacts," they noted.

The group suggested that football offers a "unifying force," but often carries a cost in the form of repetitive head collisions from tackling. Although the effects of contact sports have been studied in adults, there is less thorough research regarding how adolescents are affected.

"[The] risk of … neurodegenerative disorders … is particularly pertinent to young athletes, as a recent study has reported cases of chronic traumatic encephalopathy among young adults with a history of head impact exposure," the team explained.

Zuidema and colleagues conducted a study that included 205 adolescent football players and 70 control athletes (who participated in swimming, cross-country running, and tennis) from five high school athletic programs. All study participants were male and were matched by age and school; the majority were white.

The students underwent MR neuroimaging between the sports seasons of May to July for the years 2021 and 2022. The investigators then analyzed the MRI exam data from the two groups for cortical thickness, sulcal depth, and gyrification, and cortical surface-based resting state-functional data for breadth of localized neural activity, coherence of neural signals, and resting state connectivity.

The investigators reported key differences in the brains of the football players compared to the non-football-playing controls, noting the following:

- The football group showed significant cortical thinning, especially in fronto-occipital regions (that is, the right precentral gyrus and left superior frontal gyrus.

- Football players showed elevated cortical thickness in the anterior and posterior cingulate cortex (that is, left posterior cingulate cortex and right caudal anterior cingulate cortex).

- The football cohort had greater and deeper sulcal depth than the control groups in the cingulate cortex, precuneus, and precentral gyrus (that is, the right inferior parietal lobule and the right caudal anterior cingulate cortex).

- Football players also demonstrated lower amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation in the frontal lobe and cingulate cortex but elevated amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation in the occipital regions, as well as lower regional homogeneity in the precentral gyrus and medial aspects of the brain but higher values in the occipitotemporal regions.

The study results support previous research that has suggested that the anterior cingulate cortex, the orbitofrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the superior temporal gyrus are associated with mental well-being and are affected by contact sports, according to the team.

"[We found] evidence of discernible structural and physiological differences in the brains of adolescent football players compared with their noncontact controls … [and] many of the affected brain regions were associated with mental health well-being," it concluded.

The complete study can be found here.