Endocarditis

Clinical:

Infective endocarditis is a rare, but potentially

life-threatening disease associated with substantial morbidity and

mortality [1]. The aortic valve is involved in 50% of cases [1,5].

It is most commonly seen in IV drugs users and in patients with

prothetic heart valves (approximately 5% of patients with

prosthetic heart valves develop endocarditis and involvement of

mitral valve prostheses is more frequent [4]) [2]. Causes of early

prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE less than one year following

replacement) include perioperative contamination of the prosthesis

or cardiovascular instrumentation [9]. The most common organisms

are S aureus and S epidermidis which account for

40-50% of cases of early PVE [9].

Other predisposing conditions include calcific aortic stenosis,

congenital heart disease, HIV, and poor dentition [4]. Right sided

infective endocarditis accounts for 5-10% of all cases of and most

often invovles the tricuspid valve (isolated pulmonary valve

endocarditis is rare) [8]. Infectious vegetations form on the

valve cusps, most commonly on the ventricular surfaces of the

cusps [5]. Cutaneous manifestations result from peripheral

embolization and include petechiae, subungual splinter

hemorrhages, Osler nodes (painful transient subcutaneous nodules),

and Janeway lesions (nodular hemorrhages in distal digits [4].

Despite improvements in antibiotic therapy, surgery may be

undertaken in up to 50% of patients with IE [6]. The most frequent

indications for surgery are heart failure, perivalvular extension

with abscess formaiton, persistent sepsis, embolic events, and

large vegetation size, or a combination of factors [6].

Sterile endocarditis (nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis) is

caused by immune complex deposition that precipitates an

inflammatory reaction and secondary thrombosis [2]. NBTE has been

reported in patients with advanced-stage malignancy

(adenocarcinoma of the colon, lung, ovary, orpancreas),

hematologic disrders, connective tissue disease, SLE (Libman-Sacks

endocarditis), AIDS, and hypercoaguable states [7,9]. The

vegetations in NBTE are dense, small (under 1 cm), broad based,

and irregular in shape [7]. Lambl excresences which occur as

filiform thrombi strands arising from the margins of the valve

leaflets are associated with nonbacterial endocarditis associated

with malignancy [9].

Complications:

Vegetation embolism- vegetations larger than 10mm in diameter have a 60% embolic incidence, compared to 23% for those smaller than 10 mm [1].

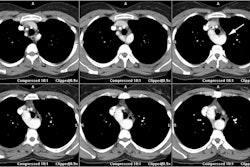

Perivalvular extension/perivalvular abscess/valvular aortic pseudoaneurysms- in 33-58% of patients, infective endocarditis of the aortic valve may extend into the annulus (perivaivular extension [6]) resulting in the formation of an aortic root abscess [1]. Perivalvular extension is common and affects 10-40% of patients with native valve IE and 56-100% of patients with prosthetic valve IE [6]. A perivalvular abscess may result in atrioventricular block or bundle branch block and persistent sepsis despite antibiotic use [1]. The presence of an aortic root abscess also complicates valve replacement and increases the risk for valve dehiscence [1]. An abscess does not communicate with the cardiac chambers [6]. A pseudoaneurysm does communicate with the intracardiac blood pool and will appear as a complex, pulsatile contrast filled perivalvular area on dynamic cine gated imaging [6]. Cardiac-gated CTA may be limited for the detection of small (4mm or less) vegetations and small valve perforations [6].

Valve perforations- small defects in the valve tissue that allow retrograde flow of blood into the preceding cardiac chamber [6].

X-ray:

Transesophageal echo: TEE is the most reliable means of

identifying vegetations because of their small size (2-3mm) [2].

The sensitivity and specificity of TEE in infective endocarditis

is 87-100% and 91-100%, respectively [3].

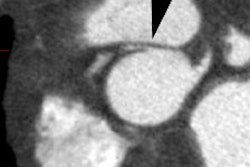

CT: Vegetations larger than 10 mm in diameter are almost always

detected by CT and are typically located on the ventricular side

of the aortic valve (low-pressure side of the valve) or the left

atrial side of the mitral valve [1,6]. The risk of embolization is

highest with large (>10mm) mobile vegetations [6].

PET: PET imaging has a limited role in the imaging of infective

endocarditis, however, valve uptake can be seen and resolve

following treatment [3].

REFERENCES:

(1) AJR 2010; Gahide G, et al. Preoperative evaluation in aortic

endocarditis: findings on cardiac CT. 194: 574-578

(2) AJR 2011; Hoey ETD, et al. Cardiovascular MRI for assessment

of infectious and inflammatory conditions of the heart. 197:

103-112

(3) J Nucl Cardiol 2011; Kenzaka T, et al. Positron emission

tomography scan can be a reassuring tool to treat difficult cases

of infective endocarditis. 18: 741-743

(4) Radiographics 2011; Kanne JP, et al. Beyond skin deep:

thoracic manifestations of systemic disorders affecting the skin.

31: 1651-1668

(5) Radiographics 2012; Bennett CJ, et al. CT and MR imaging of

the aortic valve: radiologic-pathologic correlation. 32: 1399-1420

(6) J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2012; Entrikin DW, et al. Imaging

of infective endocarditis with cardiac CT angiography. 6: 399-405

(7) Radiology 2013; van Werkum MH, et al. Case 190: Papillary

fibroelastoma of the pulmonary valve. 266: 680-684

(8) J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2015;

Passen E, PharmD ZF. Cardiopulmonary manifestations of isolated

pulmonary valve infective endocarditis demonstrated with cardiac

CT. 9: 399-405

(9) Radiographics 2016; Murillo H, et

al. Infectious diseases of the heart: pathophysiology, clinical

and imaging overview. 36: 963-983