Coronary Artery Aneurysm:

Clinical:

Small coronary artery aneurysms are found in 1% to 5% of patients undergoing coronary angiography [2,3]. The incidence is higher in men than women [6]. Aneurysms are usually located in the proximal portion of the major coronary arteries [3]. Most patients with coronary artery aneurysms are asymptomatic [6], but patients can present with angina, infarction, CHF, or sudden cardiac death [8]. Complications include thrombus formation, distal embolization, shunt formation, and rupture [7]. Treatment is typically conservative and aimed at preventing thromboembolic complications with anticoagulant therapy and antiplatelet drugs [6]. Surgery is indicated in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease or evidence of embolization and in those patients with saccular aneurysms due to an increased risk of rupture [6]. Percutaneous treatment with noncovered or coated stents is another option in patients with a fistula that needs closure [6]. Etiologies include:

1- Atherosclerotic disease (most common etiology accounting for 50% of cases [7]). Atherosclerotic aneurysms are more common in male patients and most patients present in their seventh decade of life [10]. They are usually multiple (in one-half to two-thirds of cases [10]) and involve more than one coronary artery [6]. The RCA is the most commonly involved (40-61%) followed by the LAD (15-32%), and the left circumflex (15-23%) [6]. Left main trunk involvement is rare (0.1-3.5%) and its presence is usually associated with significant underlying 2-or-3 vessels coronary artery disease [6].

2- Vasculitis - Kawasaki's disease [most common childhood cause], Takayasu arteritis, Behcet disease [6,10].

A. Kawasaki disease (KD) or mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome is an acute self-limited multisystemic panarteritis/systemic vasculitis [6] which affects medium and small arteries (the left subclavian artery is the most commonly affected [8]). It occurs predominantly in children under the age of 5 years (80% of cases occur in patients under the age of 5 [10] and the peak age at onset is 2-3 years [9]). KD is the second most common childhood vasculitis after Henoch-Sch?nlein purpora [8,9]. KD is more common in boys (1.5-2:1) [9].

The criteria for diagnosis of KD include fever for 5 days or more without a cause and four of the following: bilateral conjunctival injection; mucous membrane changes (oropharyngeal mucosal erythema, strawberry tongue); extremity abnormalities including erythema of the palms or soles; rash; or cervical lymphadenopathy [8]. A pericardial effusion can be found in 30% of patients [8]. Treatment is with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy combined with aspirin [10,11].

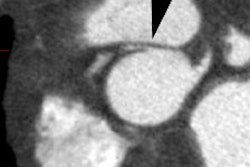

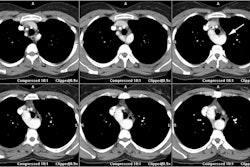

Coronary findings in KD include coronary artery ectasia and aneurysms, and lack of normal tappering [9]. Coronary artery aneurysms are frequently the result of KD- they occur in 15-25% of untreated children with the disease [10]. Even with treatment, 5-10% of patients will still develop a CAA [10]. The aneurysms typically develop during the acute phase of the disease (usually within 10-14 days to 4 weeks of onset) [8,10]. Although other authors indicate coronary artery aneurysms generally occur within 3 to 6 months of the onset of the acute illness. Risk factors for developing CAA include the duration of the fever, a younger patient age (< 1 year), male gender, lack of response to treatment, and delay in diagnosis [[11]. Approximately 50-75% of the aneurysms regress by two years after the onset of the disease- aneurysms that persist after this time are unlikely to regress [5,6,10]. The aneurysms are more likely to involve the proximal portion of the coronary artery [8] and/or near bifurcations [11] - with the proximal LAD and proximal RCA being the most common sites [9], followed by the left main, left corcumflex, and distal RCA [10].

The younger the patient the greater the likelihood for developing aneurysms (up to 79% in infants under the age of 6 months). Coronary artery aneurysms are classified as small (less than 5 mm), medium (5 to 8 mm), and large/giant (greater than 8 mm) [6,9]. Large aneurysms (>8mm) have a higher risk of complications such as thrombosis and infarction [8,9]. Small aneurysms may regress [9], but medium and large aneurysms remain unchanged or may even progress to stenosis. Other factors associated with spontaneous regression include age less than 1 year, saccular morphologic structure, and distal location [6]. Early treatment of Kawaski's with aspirin and high-dose intravenous gamma globulin has been proven to be effective in reducing the prevalence of coronary artery aneurysms [1]. Since the introduction of gamma-globulin therapy, coronary artery aneurysm or ectasia is now seen in only 5% of cases [6].

Other cardiac findings in KD include myocarditis and pericarditis [9].

B. Takayasu arteritis: Coronary involvement by Takayasu arteritis is seen in 12% of cases (10-30% of patients [8]) [6]. Coronary lesions include ostial stenosis (most common), arteritis (focal or diffuse), and aneurysm formation (in up to 8% of patients- most often young or middle aged women [10]) [8].

C. Behcet disease: A chronic relapsing systemic vasculitis that more commonly involves the veins (29%) than arteries (8-18%) [10]. Coronary artery involvement is reported in 1% of patients and can result in aneurysms or thrombosis [10].

3- Mycotic (infectious)- embolic disease

4- Following PTCA/iatrogenic [2,3,6]. Coronary artery aneurysms can be found in up to 4% of cases four months following PTCA and dissection at the time of the procedure is associated with a greater risk [3]. These are typically saccular would more appropriately be defined as pseudoaneursyms [8]. Placement of drug-eluting or bare metal stents has also been implicated in CAA formation (0.8-1.1% of patients) [10].

5- Coronary artery fistula- due to compensatory dilatation of the vessel [6].

6- Coronary artery aneurysms can also very rarely be congenital [2] and can be associated with congenital syndromes such as Loeys-Dietz syndrome [8]. Congenital lesions most commonly involve the right coronary artery, are generally large, and affect young patients [2]. Congenital aneurysms have been reported to rupture into the pericardial space, causing cardiac tamponade (they can also rupture into the right atrium) [2].

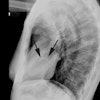

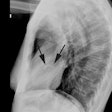

X-ray:

Coronary artery aneurysms are defined as focal abnormal dilatation to more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent normal coronary artery involving less than 50% of the total length of the vessel [4,6]. In children, a coronary artery aneurysm is present when the diameter of the lumen is more than 3 mm in children younger than 5 years, or more than 4 mm in those 5 years or older [6]. A giant aneurysm has been defined when the maximal diameter exceeds 20 mm in adults or 8 mm in children [6] (other authors suggest that an adult giant CAA has a diameter larger than 5 cm [10]). Aneurysms can be saccular or fusiform on the basis of their morphologic appearance [5,6]. Saccular aneurysms are frequently seen distal to an area of proximal related stenosis, are often multisegmental, and are more prone to thrombosis and rupture [6].

If the process diffusely involves the vessel (i.e.: dilated >1.5 times and elogated involving more than 50% of the length of the vessel)- it is referred to as ectasia [4,5,6]. Ectasia is more common than coronary artery aneurysms [6]. Ectasia tends to occur in association with atheroscerotic disease and the vessels develop a tortuous appearance [5]. Ring calcifications can be seen in up to 36% of adults with coronary artery aneurysms. Most atheromatous aneurysms are small and thick walled with a low risk for spontaneous rupture [2].

REFERENCES:

(1) Radiology 1998; Chung CJ, et al. Kawasaki disease: A review. 208: 25-33

(2) AJR 2001; Konen E, et al. Giant right coronary aneurysm: CT angiographic and echocardiographic findings. 177: 689-691

(3) Acta Cardiol 2001; Dubois CL, Vandercoort PM. Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of coronary arteries and saphenous vein coronary artery bypass grafts: a case report and literature review. 56: 263-267

(4) Radiographics 2007; O'Brien JPO, et al. Anatomy of the heart at multidetector CT: what the radiologist needs to know. 27: 1569-1582

(5) AJR 2008; Takaki MTT, et al. Nonatherosclerotic cardiovascular findings on MDCT coronary angiography: a selection of abnormalities. 190: 934-946

(6) Radiographics 2009; Diaz-Zamundio M, et al. Coronary artery aneurysms and ectasia: role of coronary CT angiography. 29: 1939-1954

(7) J Nucl Cardiol 2010; Collins AM, et al. Evaluation of coronary artery aneurysm and stenosis using open-source myocardial perfusion SPECT and coronary computed tomographic angiography image fusion software. 17: 699-705

(8) AJR 2010; Johnson PT, Fishman EK. CT angiography of coronary

artery aneurysms: detection, definition, causes, and treatment.

195: 928-934

(9) Radiographics 2017; Saling LJ, et al. Abnromalities of the

coronary arteries in children: looking beyond the origins. 37:

1665-1678

(10) Radiographics 2018; Jeudy J, et al. Spectrum of coronary

artery aneurysms. 38: 11-36

(11) Radiographics 2018; Broncano J, et al. CT and MR imaging of cardiothoracic vasculitis. 38: 997-1021