If the current crop of TV shows is any indication, medical imaging is primed to replace forensics as the cool crime-fighting science. On the Fox drama "Bones," FBI doctors used whiz-bang 3D virtual reconstruction to identify homicide victims.

Imaging has also popped up on all the incarnations of "CSI," most often in the context of forensic autopsy, although one episode of "CSI: Miami" did raise hackles when iodine-131 was used as a murder weapon.

Of course, in these cases, imaging was used on the deceased victim. But in real-life crime dramas, imaging is being deployed in a new context -- as a defense tool for those looking to back up a plea of legal insanity.

Consider the recent trial of Dena Schlosser, who was accused of fatally dismembering her 10-month-old daughter with a kitchen knife in the family's apartment in Plano, TX. During her first trial, which ended in a hung jury, Schlosser's team failed to convince the jury that voices in her head drove her to commit murder.

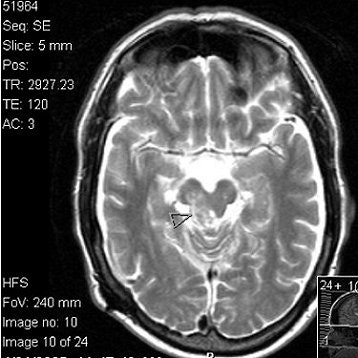

During Schlosser's retrial, defense attorney David Haynes introduced new evidence that Schlosser had a midbrain tumor, which was spotted after she underwent a functional MRI (fMRI) test. The new defense tactic was that the voices Schlosser had heard were caused by this inoperable brain tumor. Schlosser was subsequently found not guilty by reason of insanity earlier this year.

|

| Dena Schlosser claimed that a brain tumor induced hallucinations, which drove her to fatally mutilate her daughter. Image courtesy of Collin County Office of Public Information. |

Schlosser beat serious odds when her brain tumor was confirmed with the MR scan. Others are attempting to do the same. It would seem that defense attorneys order up MRI, PET, and SPECT scans so often that the topic inspired a lively debate in the AuntMinnie.com General Radiology Forum.

"We had an attorney in the state's public defender office (who) would get a PET or MRI (on the taxpayer's dime) on every capital murder defendant," stated one Forum member.

Such complaints inspired AuntMinnie.com to investigate the use of scanning as a psycholegal defense tool (and before "Law & Order" beat us to it). Can a scan actually convince a jury that a person is not at fault for committing a heinous act of violence against another human being? Under what circumstances are scans most likely to be ordered? And how much liability do radiologists carry when they are asked to perform such exams?

Different states, different standards

Certainly defense teams can request an imaging exam, find a doctor to perform and interpret it, and submit the results as evidence in their client's favor. But how likely are the courts to admit the evidence, especially as a bolster for the tricky insanity plea? The answer varies from state to state.

"The Texas formulation of the insanity defense is one of the tightest in the 50 states," said David Haynes, Schlosser's attorney, in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "In Texas, a person is insane if, as a result of a severe mental disease or defect, he did not know that his conduct was wrong. Unless a defendant can show a long history of documented bizarre behavior that has been observed by lay persons, he has no chance to use the insanity defense successfully."

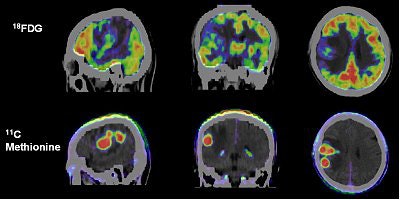

|

| Primary glioma imaged on FDG-PET and 11C-methionine PET, revealing tumor glucose utilization and protein synthesis respectively. Image courtesy of Siemens Medical Solutions and Huashan Hospital, Shanghai. |

Before the MR scan and the brain tumor, Schlosser had been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, for which hallucinations are a classic symptom. But that diagnosis alone was considered inadequate proof of incompetency by the Texas court.

|

Above, T1-weighted postcontrast axial image from the MRI series undergone by Dena Schlosser. Below, an axial diffusion-weighted image. Schlosser's neurologist examined Schlosser after her first trial and, based on the MRI exam, testified that midbrain injuries could cause visual hallucinations. Schlosser had previously told psychiatrists that she believed God wanted her to cut off her child's arms, as well as her own arms, legs, and head (Dallas Morning News, April 3, 2006). Images courtesy of David K. Haynes, Attorney at Law.

|

In 1998, a Florida death row inmate Michael Robinson -- who had pleaded guilty to first-degree murder -- decided he wanted to serve a life sentence instead. In an effort to show mental incompetence, his defense counsel put in a bid for a state-sponsored PET scan, which was deemed too expensive by the state, and then a SPECT scan -- dubbed "a poor man's PET scan" by the defense. Robinson claimed his constitutional right to due process was violated when Florida denied him both scans.

Other states are more lenient. In Massachusetts, a judge felt a homicide defendant with attention deficient/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), traumatic brain injuries, and a language disability actually may have been unable to control his behavior. The court blamed the defense attorney for not mentioning those details during the trial, thereby depriving the accused of an insanity defense, and the defendant was granted a new trial.

In the U.S. territory of Guam, Joseph Hughes Valenzuela, accused of repeatedly stabbing his wife with a kitchen knife in 2003, was actually ordered by the court to undergo a brain scan. His criminal trial is set for June 30.

In New York City, Peter Braunstein underwent PET scans at the request of his attorney, Robert Gottlieb. Braunstein allegedly set a small fire in an apartment building and impersonated a firefighter to gain access to the victim's apartment. He is accused of drugging the woman and raping her repeatedly for 13 hours, before fleeing with a pair of her shoes.

|

| Above, Peter Braunstein. Image courtesy of Gawker.com. Below, Braunstein's PET scan. Image courtesy of the Law Offices of Robert C. Gottlieb. |

|

A neuropsychiatrist who reviewed the images said that Braunstein's scans showed frontal lobe deficiencies consistent with schizophrenia. Additionally, a psychologist hired by the defense interviewed Braunstein at Rikers Island and said that he suffered from "psychotic breaks with reality, a systematized paranoid delusion and compromised ability to control his impulses."

In December 2005, Braunstein pleaded not guilty to charges of sexual abuse, arson, kidnapping, burglary, and robbery. Gottleib is rumored to be planning a psychiatric defense (New York Daily News, June 2, 2006).

A felon in your future?

Many types of psychoses and dementias are identifiable by brain anomalies or pathologies on imaging, so the appeal of imaging to defense attorneys is a given, especially as technologies become more cost-effective.

A 2001 study found that among forensic referrals for competency to stand trial the largest diagnostic category was schizophrenia (44%), followed by psychosis (43%). Overall, 18% of the present sample was found to be incompetent to stand trial, while 12% were found to be not criminally responsible or "insane" (Behavioral Sciences & the Law, September 17, 2001, Vol. 19:4, pp. 565-582).

Another study from the Yale University Child Study Center in New Haven, CT, found that of the 18 males in their patient sample -- all of whom were condemned to death -- all showed signs of prefrontal cortex impairment. In addition, "83% had signs, symptoms, and histories consistent with bipolar spectrum, schizoaffective spectrum, or hypomanic disorders" (Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 2005, Vol. 32:4, pp. 408-429).

What is the role of radiologists when requests for these scans come their way? Does the imaging expert's obligation end once this "patient" is out of the scanner and/or once the films have been read, or is he or she now a reluctant participant in a criminal case?

First, the type of practice can makes a difference. A radiologist in private practice can always refuse a referral to image a violent criminal. On the other hand, those who work for government institutions (federal or state hospitals) may not have that option, although prison-based doctors have successfully bowed out of certain tasks citing ethical concerns (Boston Globe, February 21, 2006).

When defendants are referred for imaging, the order may come from another physician who is acting on the request of a judge or attorney, or if the defendant has been sent to a particular institution for competency evaluation. Occasionally, proper protocol is ignored and attorneys will order imaging exams as will physicians who are acting as an expert witness, but are not licensed to practice within the trial state.

Radiologists can refuse to provide medically unauthorized exams, although they risk being called on the carpet for insubordination, especially if a supervisor has approved the order. But that may be lesser of two evils -- accepting such a referral does carry some legal risk. Conducting an imaging exam without a medical indication is questionable. Imaging experts also may be held liable for performing medical exams on referral from someone who is not a doctor.

The request for the scan should come directly from a medical professional, although the implicit understanding is that the psychiatrist or neurologist is asking on behalf of an attorney, said Dr. Harry Zibners, chairman of the medicolegal commission of the American College of Radiology (ACR).

As for reading the scan itself, Zibners recommended that radiologists approach it as they would in a routine clinical setting, including a working knowledge of the person's relevant medical history.

"I would not view this any differently than any other case that I agreed to read," Zibners told AuntMinnie.com. "I want to have some kind of history. I would read it and interpret it like I would anything else. That's what my job is."

For the written report, Zibners again suggested that radiologists walk the straight and narrow. While it may be obvious to everyone involved in this case that the defense team has an agenda, the radiologist need not play into that by making any connection between results of the scan and the defendant's violent actions.

"I would not (make that connection) because I'm not a psychiatrist, and I don't have that kind of expertise," he said. "The radiologist's job is to demonstrate an abnormality if there is one. But I think the attempt to connect these abnormalities with certain kinds of behavior is overdrawn. I don't think it's appropriate to say in a report 'There's a certain kind of abnormality in the frontal lobe so that might explain why this guy killed someone.'"

If the medical expert working for the defense requests a consultation to go over imaging exam results, Zibners said taking that meeting is up to the individual radiologist. "It's like any other malpractice litigation. The radiologist has to decide whether he will or he won't. I bet most people would say 'No.' I think that's why the radiologists are upset (by these requests) because they feel like they are being set up. They don't need to get pulled into that (case)."

|

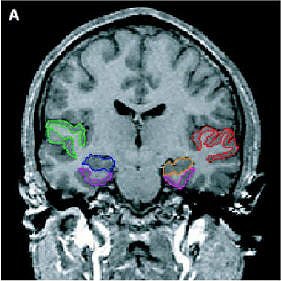

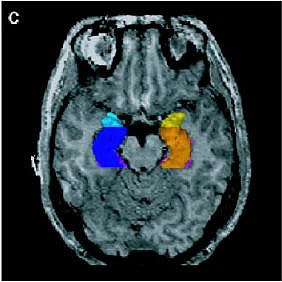

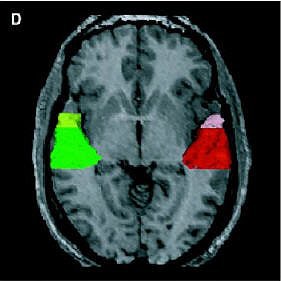

| Above, regions of interest (ROI) examined in MRI study of patients with first-episode schizophrenia or affective psychosis and normal comparison subjects. Top (A) is a 1.5-mm coronal slice of the temporal lobe; the ROI used to evaluate the temporal structures are outlines. The gray matter of the superior temporal gyrus is shown in red (subject left) and green (subject right); more medially, the amygdala-hippocampal complex is shown in orange (left) and blue (right) with the parahippocampal gyrus underneath in pink (left) and purple (right). Below, a left lateral view of a 3D reconstruction of the cortical surface with the anterior superior temporal gyrus (light pink) and posterior superior temporal gyrus (red). |

|

There is a chance that the imaging expert will be called to testify, but it's a slim chance. What attorneys really want is an image that will sway a jury and give weight to a psychiatric evaluation, not testimony from someone who may not stick with the defense team's strategy.

"Lawyers don't want an unfriendly witness," said Dr. Leonard Berlin, chairman of the department of radiology at Rush North Shore Medical Center in Skokie, IL.

|

| Same subject. Above and below, axial MRI is used to present top-down views of the 3D reconstruction of the amygdala-hippocampal complex and parahippocampal gyrus. All images: Figure 1, Hirayasu Y, Shenton ME, Salisbury DF, et al. "Lower Left Temporal Lobe MRI Volumes in Patients with First-Episode Schizophrenia Compared with Psychotic Patients With First-Episode Affective Disorder and Normal Subjects," (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:1384-1391). |

|

If a subpoena is issued, don't even think of ignoring it, Berlin said. "If subpoenaed by a court, you must obey that order. If you don't, you're in contempt of court and can be jailed. But you cannot be forced, except in rare circumstances, to testify as an expert witness."

If subpoenaed to testify, consult an attorney first and the malpractice insurance carrier as they often will cover lawyer fees. The ACR offers practice guidelines on being an expert witness in radiology.

Finally, Zibners suggested that if a radiologist is contacted directly by the defense team for a consultation, the practice or hospital's legal counsel should be notified about the request as a courtesy, even if the radiologist refused the meeting.

Endless possibilities

So what are defense teams looking for with imaging? In most cases, they order neurological scans that will cast their client's violent actions in a slightly more forgiving light. And radiologic forensic studies have indicated that tendencies toward violent behavior are manifested physically.

For instance, an FDG-PET study showed that temporal lobe anomalies can be linked to violent crimes, particularly homicide and sexual assault (American Journal of Neuroradiology, April 1997, Vol. 18:4, pp. 625-63).

|

| Above, a coronal FDG-PET scan in a control subject. Note relatively homogenous temporal lobe metabolism. Below, a coronal FDG-PET scan in a 20-year-old male, with a history of unpredictable behavior and domestic violence, who shot and raped his stepmother and hid her body in a closet. Note low metabolic activity in medial temporal lobes. |

|

| D Seidenwurm, TR Pounds, A Globus, PE Valk, Abnormal Temporal Lobe Metabolism in Violent Subjects: Correlation of Imaging and Neuropsychiatric Findings. American Journal of Neuroradiology, Volume 18, Issue 4, pp. 625-631, April 1997. © by American Society of Neuroradiology. |

In a poster presentation at the 2006 International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) meeting in Seattle, Danish researchers used 3D volumetric MRI to demonstrate that major depression caused measurable structural changes in the thalamus, inferior and middle prefrontal gyrus, and occipital lobe. Severe postpartum depression was the defense mounted by Andrea Yates' attorneys when she was tried in 2002 for drowning three of her five children in the bath tub. Yates is currently undergoing a re-trail and has pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity (CNN.com, February 7, 2005).

Physical illness as the basis for an insanity defense has also relied on imaging to prove a disconnection -- or disprove a connection -- between a violent act and the defendant a la Dena Schlosser.

In 1998, Concord, CA-based physician Gary Parkison claimed AIDS-related dementia made him legally insane -- and that's why he plotted to hire a hit man to kill his former lover in a life insurance scam. Parkison was also convicted of setting fire to his office to dodge his lease.

|

| Coronal MR scans from a chronic schizophrenic (above) and normal comparison subject (below). Note increase in CSF in left amygdala-hippocampal complex. Images courtesy of Schizophrenia Research Project and Psychiatry Neuroimaging Laboratory, Harvard University, Boston. |

|

Parkison was diagnosed with AIDS in 1992 and, after he was jailed, an MRI scan showed brain lesions. In an HIV-positive patient, these lesions can lead to poor impulse control and a lack of judgment, according to the psychiatrist who examined Parkison (SFGate.com, May 1, 1998).

Liar, liar

And what if there are no obvious disease processes or mitigating psychological problems? Then bring on the "No Lie MRI." Recent research has focused on differentiating truth tellers from those who are being less than honest. A study done at the University of California, Los Angeles, used MRI to determine that pathological liars had 22% more prefrontal cortex white matter and 14% less gray matter than normal controls (British Journal of Psychiatry, October 2005, Vol. 187, pp. 320-325).

An earlier controlled fMRI study at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles also showed that schizophrenics showed a distinct lack of functioning in the prefrontal region of the brain (Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2002, Vol. 28:3, pp. 501-513).

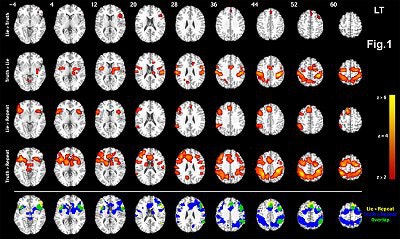

In another study, Dr. Daniel Langleben, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, showed that deception is distinguishable from truth by increased prefrontal and parietal activity, and that fMRI clearly revealed frontal lobe activity associated with lying (Human Brain Mapping, December 2005, Vol. 26:4, pp. 262-272).

|

| Group analysis showing significant differences in brain activation between Lie, Truth, and Repeat Distracter conditions. Row 1: Truth > Repeat Distracter; row 2: Lie > Repeat Distracter; row 3: Lie > Truth (blue scale) Truth > Lie (red scale). Images are displayed over a Talairach-normalized template in radiological convention. Significance thresholds for all contrasts based on spatial extent using a height of z ≥ 2.57 and cluster probability p ≤ 0.05, except Lie > Truth (blue scale) presented at a z ≥ 1.64, uncorrected. Image courtesy of Dr. Daniel Langleben. |

Could defense attorneys start ordering MRI exams as "proof" that their clients are telling the truth when they claim they suffered from diminished mental capacity at the time of the crime and did not understand their actions?

Possibly. According to Langleben, the No Lie MRI system, when used in combination with a carefully controlled query procedure, demonstrated 80% to 92% accuracy versus a polygraph test, which turns in an accuracy of 50% to 90%.

"The problem with polygraph is that it seems to be operator-dependent and thus susceptible to manipulations," Langleben told AuntMinnie.com. With the 3-tesla MR test, "no one 'reads' the scan," he said. "The data is automatically processed with preset thresholds of significance."

The No Lie MRI system has not been used in a U.S. criminal court case to date, although fMRI lie detection and brain mapping were used in 2006 to convict a rapist in Mumbai, India. Abhishek Kasliwal, 27, was accused of kidnapping and raping a 52-year-old woman at the compound of a mill owned by his father. Kasliwal underwent brain mapping at the Central Forensic Science Laboratory in Bangalore as a routine part of the investigation (IBNlive.com, March 28, 2006).

Neuroethics

While courts seem to be more open to using imaging in criminal cases, ethical questions still need to be answered. Neuroethics is the name given to a new field that encompasses the array of issues emerging from different branches of clinical neuroscience (neurology, psychiatry, psychopharmacology) and basic neuroscience (cognitive neuroscience, affective neuroscience), including the use of functional neuroimaging.

"Most of neuroethics theory is highly speculative at the moment," said Professor Margaret Somerville, founding director of McGill University's Centre for Medicine, Ethics and Law in Montreal. Scanning for insanity or deception "leads into a whole lot of other things," according to Somerville. "What if you find someone's got a hyperaggressivity gene? Does that mean they couldn't help it if they did something aggressively?" she said.

There are other ethics issues as well, such as the application of imaging for nonmedical reasons and the potential violation of informed consent if the attorney is keen on the scan but the accused isn't interested in being tested, whether by choice or an inability to make those kinds of decisions. "The patient has to agree. It can't be done against a patient's will," Berlin said.

Haynes agreed with Somerville that the future of brain scans in court appears limited. "The law proceeds on the assumption that people decide to do bad things out of their evil hearts and minds," he said. "This is the basis of the criminal law. If we're now going to say we can scan a person and see why he engages in violent behavior, then why are we going to put him on trial or punish him at all?"

By Sydney Schuster

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

June 29, 2006

With additional reporting by AuntMinnie.com staff writer Shalmali Pal.

Related Reading

MRI reveals patterns of neurological abnormalities in schizophrenia, April 4, 2006

Brain abnormalities linked to pathological lying, October 18, 2005

PET-sonography combination highlights memory differences in schizophrenics, June 2, 2003

The truth is out there: fMRI uncovers human deception, June 11, 2003

MRI findings predict development of symptomatic psychosis, December 11, 2002

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com