CT and MR techniques depict pathology beyond the range of endoscopy

Enterography is the story of progress made possible from better chemistry applied to contrast media development and the recent leaps in engineering that have revolutionized CT.

This unique imaging technology is directed at the small bowel, an overlapping, undulating, 22-ft-long section of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract remotely located between the stomach and large intestine.

Compared with other organs, the small bowel is subject to a relatively low incidence of disease, according to Dr. Dean Maglinte, a distinguished professor of radiology and imaging sciences at Indiana University School of Medicine. But the symptoms of disorders that do affect it are often nonspecific. For these reasons, the primary role of small-bowel imaging is to rule out the presence of fairly uncommon pathology. These are inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and small bowel tumors.

About 80% of the demand for small-bowel imaging stems from Crohn's disease, which affects up to 600,000 Americans. Disease prevalence has increased 31% since 1991, with pediatric patients accounting for 25% to 30% of the affected population (Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, March 2007, Vol. 13:3, pp. 254-261).

Roles for diagnostic imaging

','dvPres', 'clsTopBtn', 'true' );" >

Click to enlarge.

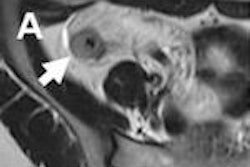

Patient with active ileocolonic Crohn's disease.

Small-bowel imaging guides therapeutic management of Crohn's disease by informing the clinician about the location, extent, and activity of pathology, according to Dr. Sam Stuart, a radiologist with Royal Free Hospital in London. Imaging aids diagnosis, monitors progression, assists treatment, and identifies small-bowel strictures that may need surgical resection.

CT enterography (CTE) has largely replaced small-bowel follow-through as the imaging modality of choice for Crohn's disease. Its popularity stems from its ability to noninvasively investigate extraintestinal effects of inflammatory small-bowel disease located outside the reach of x-ray barium imaging.

The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, adopted CT enterography for routine clinical use after the publication of a pivotal study by its own Dr. Craig Solem and colleagues in 2008 (Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, August 2008, Vol. 68:2, pp. 255-266).

Solem's team prospective efficacy study compared the relative abilities of CT enterography, capsule endoscopy, ileocolonoscopy, and small-bowel follow-through to diagnose Crohn's disease and determine whether it was active or inactive.

Based on experience with 42 patients, the researchers found that ileocolonoscopy is only slightly more accurate than CT enterography (86% versus 85%) for diagnosis. It was far more sensitive than small-bowel follow-through (82% versus 65%) and significantly more specific than either capsule endoscopy or small-bowel follow-through (89% versus 53%).

"Solem's study showed us that small-bowel follow-through was inferior," said Dr. David Bruining, an assistant professor of gastroenterology at the Mayo Clinic. "One of the reasons we have been pushing forward with CTE is because it is a better test."

Members of Mayo Clinic's small-bowel imaging group also were drawn to CT -- and later MR -- enterography because of endoscopy's limitations. Endoscopes are sometimes unable to extend to areas of disease involvement, and endoscopy findings do not necessarily correlate with disease activity.

"It is not enough to see the patient's symptoms and to tell patients that they are failing therapy. We need objective evidence," Bruining said. "That is where CT or MR enterography has made a big impact in practice."

CT enterography utilization increased steadily at the Mayo Clinic after 2006. It reached a plateau in 2009, with the initial adoption of MR enterography (MRE). Most of the growth in the past two years has shifted to MRE, Bruining said.

Keys to CTE's diagnostic power

Enterography could not have been developed without high-speed multislice CT. Its development moved in lockstep with the progress of CT from four-slice acquisition in the late 1990s to current 320-detector-row scanners that can complete a whole-body scan in three seconds. Such ultrahigh temporal and spatial resolution can be focused on the small bowel to freeze motion for even a pain-ridden child, while rendering diagnostically superb images of the intestinal lumen, mucosa, and extraintestinal region.

The full extent of the benefits from multislice CT were not revealed, however, until radiologists shifted away from positive contrast material that was so bright that it washed out indications of inflammation in the bowel wall, according to Dr. Peter Higgins, PhD, an assistant professor of gastroenterology at the University of Michigan.

','dvPres', 'clsTopBtn', 'true' );" >

Click to enlarge.

Increased mesenteric vascularity.

The problem was solved when researchers inadvertently tried a negative oral contrast medium.

"It became apparent that just filling the small bowel with negative contrast, food, or fluid was actually better than very bright contrast," Higgins said.

Decades of experience with barium imaging taught radiologists the value of complete bowel dissention for ensuring thorough examination. The use of neutral enteric contrast agents has proved to be especially well-suited for this role. Such agents allow water in the gut to remain there without bowel wall absorption, Higgins said.

Complete small-bowel distention requires lots of oral contrast. The protocol for routine CT enterography at the Mayo Clinic calls for patients to drink 1.35 L of it in the two hours before imaging. The radiologist also administers intravenous iodinated contrast to enhance extraluminal structures.