Constrictive Pericarditis:

Clinical:

Acute pericarditis is usually idiopathic (80-85% of cases) and

these

care are generallly presumed to be viral in origin- typically

coxsackie,

parvovirus B19, herpes virus 6, echovirus, and HIV [4,5]. Less

common

causes include uremia, certain drugs (hydralazine, procainamide),

hypothyroidism, TB, autoimmune disease, and neoplastic pericardial

infiltration [4,5]. It can

also be seen in about 10% of patients following transmural

myocardial

infarction (this is called Dressler

syndrome when the onset is delayed and it is related to an

autoimmune

origin) [4,5]. Iatrogenic causes include post radiation therapy

for

breast cancer or mediastinal tumors, follwoing cardiac surgery or

percutaneous interventions, pacemaker insertions, or catheter

ablations

[5]. Acute pericarditis is often accompanied by some degree of

myocarditis (myopericarditis) [5].

With acute pericarditis there is

usually only minimal pericardial thickening [4]. Late gadolinium

enhancement may be seen and characteristically localizes along the

pericardium or epicardial layer [4]. A pericardial effusion, if

present, is usually small [4]. Most cases of acute pericarditis

are

benign and most patients respond favorably to treatment with

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [5]. The condition may

progress to

chronic sclerosing pericarditis which is characterized by

fibroblasts

and collagen deposition that leads to a stiff pericardium

(constrictive

pericarditis) [5]. The risk of constrictive pericarditis after

acute

pericarditis is very low in viral or idiopathic pericarditis (less

than

0.5%), but is relatively frequent in purulent and tuberculous

pericarditis [5]. Post radiation and post operative constrictive

pericarditis have become some of the most frequent causes of the

disorder [5].

Constrictive pericarditis results in impaired diastolic filling

of

the heart due to

fibrosis and thickening of the pericardium- pressures between the

atria

and ventricles

equilibrate. Patients present with symptoms similar to those of

CHF-

dyspnea, leg

swelling, pedal edema, hepatomegaly, and jugular venous

distention. An

associated finding

on physical exam is "Kussmaul's sign"- a paradoxical elevation of

jugular venous

pressure that occurs during inspiration.

Prior to antibiotics, TB was the most common

cause of constrictive pericarditis. Tuberculous pericarditis

occurs in

1% of

cases of TB [2]. The pericardial involvement is typically due to

extranodal

extension of lymphadenitis [2]. A constrictive pericarditis occurs

in

about 10%

of patients with tuberculous pericarditis [2]. Presently, an

antecedent

clinically inapparent viral

pericarditis is probably the most common etiology for constrictive

pericarditis. Other causes include prior mediastinal

XRT, cardiac surgery (0.2% of post-sternotomy patients), uremia,

rheumatic fever, and

collagen vascular disease. About 50% of patients demonstrate

pericardial calcification,

especially if the pericarditis was the result of a viral

(Coxsackievirus) or Tuberculosis

infection.

Clinically, it is important to distinguish constrictive

pericarditis from

restrictive cardiomyopathy- each of which have similar clinical

presentations and

hemodynamic alterations at catheterization. Pericardial stripping

(pericardiectomy) may

result in a dramatic

improvement in symptomatology. Long term survival after

pericardiectomy

is related to the underlying cause of the condition and survival

in

post radiaiton constrictive pericarditis, survival is poor [5].

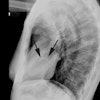

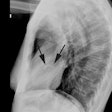

X-ray:

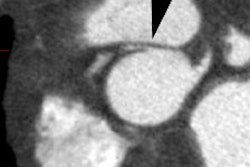

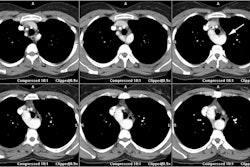

Both CT and MR effectively demonstrate pericardial thickening.

On CT, the normal pericardium measures between 1-2 mm, and a

pericardial thickness of more than 4 mm is generally regarded as

abnormal, and more than 5-6 mm is highly specific for constriction

[5].

However, normal pericardial thickness (2 mm or less) can be seen

in 14-20% of patients with constrictive pericarditis (and this may

indicate later stage disease) [5,6]. Also- up to 25% of patients

without constriction can have a pericardial thickness of 4mm

or more [6]. In patients with pericardial constriction, the IVC

will enlarge [6]. An IVC cross-sectional area ≥ 7.5 cm2 and an

IVC-to-aortic area ratio ≥ 1.6 (sensitivity 95%, specificity 76%)

can aid in the identification/confirmation of pericardial

constriction [6]. The phase of the respiratory cycle affects the

size of the IVC [6]. A dilated IVC with absence of collapse by

more than 50% in inspiration is considered a marker of increased

RA pressures [6]. Because CT imaging is performed at

end-inspiration, IVC measurements are a representation of RA

pressures [6].

Pericardial calcifications are another important sign of constrictive pericarditis (although pericardial calcificaiton is less common than in the past and is now seen in 27-28% of patients) [5]. Diffuse enhancement of the pericardium can also be seen on post contrast imaging [5]. Pericardial calcification is best appreciated on CT, but MR can provide more hemodynamic information. Pericardial calcification can be shaggy (more common and typically within the atrioventricular groove) or egg-shell (less common- spares portions of the left atrium not covered by pericardium).

On MR, the normal pericardium appears as a curvilinear line of

low

signal intensity

situated between the high signal intensity of the pericardial and

epicardial fat. It

normally measures 1 to 2 mm in thickness [5] - a width of up to 4

mm is

not

necessarily

pathologic [3]. Small quantities of pericardial fluid may be seen

normally in the superior

pericardial recess (posterior to the ascending aorta). A

pericardial

thickness of greater

than 4 mm is considered evidence of constrictive pericarditis in

the

appropriate clinical

setting. Caution must be exercised in patients with a history of

cardiac surgery or

post-pericardiotomy syndrome as they may have significant

pericardial

thickening in the

absence of clinical symptoms. Unfortunately, the absence of

pericardial

thickening does

not exclude constrictive pericarditis [4]. Cine MR can be used to

evaluate for constrictive pericarditis in cases of normal

myocardial

wall thickness [5]. Findings include narrow tubular shaped

ventricles,

a

sigmoid shaped septum,

dilatation of the right atrium, SVC, IVC, and hepatic veins, and

abnormal ventricular

movement against the pericardium. Phase contrast MR imaging of the

tricuspid valve inflow will show a restricitve filling pattern of

enhanced early filling and decreased or absent late filling,

depending

on the degree of pericardial constriction and increased filling

pressures [5]. Also- flow in the IVC shows restrictive physiology

with

diminished or absent forward, or even reverse, systolic flow,

increased

early diastolic forward flow, and late reversed flow [5].

Constrictive

pericarditis, in contrast to restrictive cardiomyopathy, is

typically

characterized by a strong respiratory-related variation in cardiac

filling (ie: enhanced RV filling on inspiration and enhanced LV

filling

on expiration [5].

REFERENCES:

(1) Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 1996; May 4(2): 237-251

(2) Radiographics 2001; Kim HY, et al. Thoracic sequelae and complications of tuberculosis. 21: 839-860

(3) AJR 2002; Kovanlikaya A, et al. Characterizing chronic

pericarditis using

steady-state free-precession cine MR imaging. 179: 475-476

(4) AJR 2011; Hoey ETD, et al. Cardiovascular MRI for assessment

of

infectious and inflammatory conditions of the heart. 197: 103-112

(5) Radiology 2013; Bogaert J, Francone M. Pericardial disease:

value of CT and MR imaging. 267: 340-356

(6) J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2014; Hammeman K, et al. Cardiovascular CT in the diagnosis of pericardial constriction: predictive value of inferior vena cava cross-sectional area. 8: 149-157