Healthcare facilities that use electronic medical records (EMRs) are documenting mammography screening exams of African-American women better than facilities that use paper records, according to an analysis of six primary care sites that provide medical services for underserved populations.

Because electronic medical records have the potential to improve the quality of documentation of a patient's medical history, researchers wanted to evaluate how accurate EMR software was compared to paper records in matching the dates of screening mammography exams with the recollection of the patients themselves. Their findings were published in the August issue of the Journal of Women's Health (2009, Vol. 18:8, pp. 1153-1162).

The study was conducted as part of the Boston Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Breast and Cervical Cancer Coalition Women's Health Demonstration Project. This community-based research project is designed to decrease racial disparities in breast cancer mortality between African-American and Caucasian women by improving screening mammography use and follow-up of abnormal results among black women.

The six primary care sites in the study consisted of an academic hospital clinic, a community health center licensed by an academic hospital, and three freestanding community health centers. African-American women between the ages of 40 and 75 treated at these healthcare facilities between 2002 and 2006 were recruited. All of the 411 study participants had a history of missed primary care or mammography appointments.

The cohort recruited represented a highly diverse group of women, and one-third were born outside the U.S. Of the participants, 200 (48.6%) reported an income of $10,000 or less, and 30% reported an income of $10,000 to $25,000. Approximately 20% at each site had a family history of breast cancer, but the patients themselves did not have known or suspected breast cancer.

Each participant was asked if she had received a mammogram within the past two years. This response was compared with any data about mammograms that had been performed over the past three years, acquired from a thorough review of electronic and paper medical records.

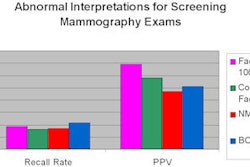

On average, 58% of the women had a mammogram as recorded in medical records within the past 24 months, whereas 75% of the women reported this. There was only a 67% agreement between medical record review and self-reporting among women with a family history of breast cancer, according to principal investigator Dr. Cheryl Clark, director of health equity research of Brigham and Women's Hospital's Center for Community Health and Health Equity in Boston.

The highest rates of agreement between self-reporting and medical record review were at two sites that had continuous availability of an EMR system between 2002 and 2006, with corroboration rates of 88% at one site and 90% at another site. In contrast, a site that had a late transition to EMRs had a corroboration rate of 64%, and a site that still used paper records had a corroboration rate of 72%.

In addition, sites using EMRs reported a higher rate of mammography compliance than those that did not. The center that only used paper records reported that 43% patients had received a mammogram in the past two years. By comparison, the sites that adopted EMR reported mammography compliance rates of 43%, 52%, 69%, and 72%.

Based on this data, the authors suggested that facilities with EMRs have a greater ability to record and capture more data about mammography screening exams. They noted that such improved documentation may facilitate a physician's review of the patient's screening history during a clinical visit. This might stimulate and increase discussion by the primary care physician about the importance of breast cancer screening, which could enhance the patient's recall of the timing of her most recent mammogram.

The study did not investigate whether physicians at any of the sites had access to mammography information systems or the RIS at Brigham and Women's Hospital. When AuntMinnie.com discussed this in an interview with Clark, she said that use of these information systems was not considered for inclusion in the study design.

Clark said that in retrospect, utilization of mammography information systems or RIS through Web access might have added a new dynamic to the study. However, use of these systems was not the focal point of the study, and because not all of the providers may have had access to these systems, the researchers felt that limiting data comparison to EMRs would achieve the objective and stay within budget.

Clark also said that based on the study's findings, it would be interesting to repeat the study with other racial and ethnic groups of women representing a low-income, underserved population. This was beyond the mandate of the commissioned study, but it could help determine if EMR data may also benefit other minority women and low-income Caucasians.

By Cynthia E. Keen

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 16, 2009

Related Reading

Breast cancer screening program identifies overdue mammography patients, March 13, 2009

Medical mistrust a factor in delayed breast cancer screening, February 6, 2009

Black women may overestimate cancer screening rates, April 28, 2008

Perceived racism does not explain low mammography rates, May 22, 2007

Mammography results poorly communicated to blacks, February 23, 2007

Copyright © 2009 AuntMinnie.com