Alcoholics who pair their chosen poison with cigarettes have a harder time regaining lost neurobiological function, according to a new MR spectroscopy (MRS) study. In addition, even after an individual has given up drinking, continuing to smoke could hamper his or her rehabilitation effort.

"Because most alcoholics continue to demonstrate a high level of nicotine dependence during abstinence from alcohol, identification of potential neurobiological and/or neuropsychological differences among smoking and nonsmoking recovering alcohol-dependent individuals may have significant implications for behavioral and pharmacological treatments of alcohol use disorders," wrote lead author Timothy Durazzo, Ph.D., from the VA Medical Center and the Northern California Institute of Research, both in San Francisco (Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, March 2006, Vol. 30:3, pp. 539-551).

Durazzo's co-authors, including Dieter Meyerhoff, Ph.D., are from the departments of radiology and psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

For this study, 25 recovering alcohol-dependent individuals (RA) were enrolled: 14 were smokers (sRA) and 11 were nonsmokers (nsRA). All RA patients were studied seven days and 35 days after abstinence. For a cross-sectional analysis, 36 RA (19 smokers, 17 nonsmokers) with about 35 days of sobriety were compared with 29 light drinkers (LD).

Inclusion criteria included the consumption of more than 150 drinks (13.6 grams of pure alcohol) per month over eight years for men and more than 80 drinks over six years for women. All sRA were active smokers before and during the study.

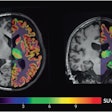

The 90-minute imaging tests were done on a 1.5-tesla scanner (Vision, Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) with structural data collected using a double spin-echo (DSE) sequence. MRI was followed by a multislice 1H MRS sequence that imaged metabolites in three slices. Metabolite concentrations for gray matter and white matter in each region of interest were calculating by overlaying the MRI dataset onto the MRS dataset.

The results showed that sRA had a higher average number of drinks per month and started drinking up to five years earlier than nsRA. After one month of sobriety, all RA showed significantly higher N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels in frontal gray matter and frontal white matter. In the frontal and parietal gray matter, as well as the front, parietal, and occipital white matter, RA had higher average choline (Cho) levels after one month of abstinence.

"Results indicate NAA and Cho concentrates ... were higher at one month of abstinence than at one week of abstinence in the RA group as a whole, and that nsRA showed greater average NAA and Cho levels across assessment points than sRA," the authors wrote.

Also, the nsRA group showed an 8% increase of frontal white matter NAA over an alcohol-free month. This same group also demonstrated Cho increases in the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes of the gray matter. In comparison, NAA concentrations only increased by 5% in the sRA group. In the parietal and occipital white matter, NAA significantly decreased. The authors concluded that "chronic cigarette smoking in RA adversely affected the magnitude of recovery of regional NAA and Cho concentrations."

Finally, they found significant relationships between metabolite changes and measures of neurocognition. Specifically, improvements in visuospatial learning were related to longitudinal increases of frontal and occipital white matter NAA. In sRA, smoking duration was inversely related to longitudinal increases in frontal white matter NAA and Cho, as well as thalamic Cho.

Durazzo's group suggested that their results may "give support to the growing clinical movement to encourage chronic smokers entering treatment for alcohol use disorders to consider concurrent participation in a smoking-cessation program." While they acknowledged that such doubling up may prove to be too much and too fast for addicts, they pointed out that going cold turkey on alcohol and cigarettes could inspire quicker brain recovery.

The study also raises another question that needs to be explored, according to Durazzo: Do smokers respond differently than nonsmokers to current pharmacological treatments for alcoholism?

In their next phase of research, the authors will follow-up with these individuals after six months of sobriety. They also plan to conduct a separate study to look at other health factors, such as diet and exercise, that may affect how the brain bounces back from alcohol abuse.

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

April 21, 2006

Related Reading

Study shows how alcohol damages the bones, December 26, 2005

Alcohol may be more neurotoxic in women, May 19, 2005

Teen binge drinking can do long-term brain damage, February 15, 2005

Heavy social drinkers show brain damage, study finds, April 15, 2004

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com