Even mild cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have serious effects on the heart and blood circulation, according to a study to be published Thursday in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The analysis of less severe COPD -- a study made practical with the use of noninvasive CT and MR rather than invasive angiography -- found that the same problems long associated with severe disease are also present in milder cases.

Dr. R. Graham Barr from Columbia University Medical Center in New York City and colleagues nationwide found that the percentage of lung tissue affected by emphysema, as well as the severity of airflow restriction, were associated with significant reductions in left ventricular (LV) filling and cardiac output but not ejection fraction.

"The magnitude of these associations was greater among participants with a history of smoking, but the association was also present among participants who had never smoked," they wrote (N Engl J Med, January 21, 2010, Vol. 362:3, pp. 220-227).

Severe COPD results in cor pulmonale, a condition characterized by elevated pulmonary vascular resistance, secondary reductions in left ventricular filling, stroke volume, and cardiac output. Whether similar changes occur in milder disease was unknown.

"We hypothesized that emphysema, as detected on computed tomography, and airflow obstruction are inversely related to left ventricular end-diastolic volume, stroke volume, and cardiac output among persons without severe lung disease," Barr and colleagues wrote.

The study was performed on participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), which examined subclinical cardiovascular disease in a broad population of 6,814 men and women.

A subgroup of 2,816 individuals (ages 45-84; mean, 61 ± 10 years) in the present study underwent baseline measurements of endothelial function and consented to genetic analysis; patients were excluded if they had the presence of a restrictive pattern on spirometry. Most ethnicities were reflective of the U.S. population, though Asians were overrepresented at 18% of participants.

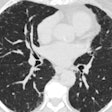

Emphysema severity was defined as the percentage of voxels below 910 HU at CT, assessed using software. The authors based this threshold on quantitative histologic comparisons and the generally mild degree of emphysema in the study. The analysis incorporated about 70% of the lung volume available on the cardiac CT exam performed as part of the MESA study, a study limitation the authors said was unlikely to have affected the results.

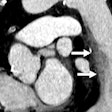

For cardiac efficiency assessment, MR (fast gradient echo cine acquisition) images were used to examine left ventricular structure and function. Scans were performed on a 1.5-tesla scanner with a four-element phased-array surface coil and electrocardiogram gating.

Spirometry was also included as part of the MESA protocol in accordance with American Thoracic Society-European Respiratory Society guidelines. Additive models were used to test threshold effects. The analysis included 13% (n = 370) current smokers, 38% (n = 1,067) former smokers, and 49% (n = 1,379) who never smoked.

The results showed a strong linear relationship between emphysema extent at CT and severity of airflow obstruction, as well as reduced stroke volume and cardiac output.

Specifically, a 10-point increase in emphysema percentage was associated with reductions in left ventricular end-diastolic volume (-4.1 mL; 95% confidence interval [CI]: -3.3 to -4.9; p < 0.001), stroke volume (-4.1 mL; 95% CI: -2.2 to -3.3, p < 0.0001), and cardiac output (-0.19 L/min; 95% CI: -0.14 to -0.23; p < 0.001).

The associations between emphysema severity and cardiac measures were stronger among individuals who were current smokers compared to former smokers and those who had never smoked, Barr and colleagues noted. Thus, smoking modified the associations between emphysema percentage with left ventricular end-diastolic volume (p < 0.001) and stroke volume (p = 0.008). The extent of airflow obstruction was also associated with left ventricular structure and function.

"For example, an increase of 10 percentage points in percent emphysema was associated with a 9.2-mL decrement in current smokers, a 4.2-mL decrement in former smokers, and a 2.6-mL decrement in those who had never smoked," and the reductions were similar for stroke volume and cardiac output, the researchers explained.

More severe emphysema at CT and greater airflow obstruction at spirometry were associated with smaller LV end-diastolic volumes, as well as reductions in stroke volume and cardiac output in the large, population-based cohort, the group wrote.

"Relations were linear across a spectrum from normal lung structure and function to moderately severe airflow obstruction and emphysema," while LV fraction was observed, they stated. The apparent effects of emphysema on LV and end-diastolic volumes were similar to those of traditional cardiac risk factors previously reported in the MESA study.

Only limited clinical data have been available in mild cases of COPD due to the invasiveness of the traditional reference measure -- angiography. "The one study [Marzluf et al] involving patients with mild-to-moderate COPD that used right-heart catheterization as a reference standard showed increase in pulmonary-artery pressure with exercise," Barr and colleagues wrote.

The mechanisms of impaired LV filing in severe COPD "include alveolar hypoxia and related pulmonary vascular changes, pulmonary hyperinflation, and ventricular interdependence," they noted.

Looking for mechanisms to explain the findings, the authors noted that alveolar hypoxia causes pulmonary-artery vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling.

"Its relevance in milder disease, however, is unclear, since alveolar hypoxia does not account for changes in the transit time of pulmonary blood flow observed in patients with mild-to-moderate COPD," Barr and colleagues wrote.

As for hyperinflation, its effects on hemodynamics are subject to debate, and the severity of airflow obstruction and LV filling in those who had never smoked suggests that the emphysema findings were not related to hyperinflation, they wrote.

"A more likely mechanism in early, mild emphysema may be the subclinical loss of lung parenchyma and the pulmonary capillary bed," they wrote. Modest reductions in capillary cross-sectional area can substantially decrease flow with only small increase in pulmonary artery pressure.

Study limitations included the use of only partial CT lung images acquired during a cardiac scan. In addition, lung function was acquired some four years after the other measures. They noted that cross-sectional studies can be subject to reverse causality and selection bias, and that cardiogenic pulmonary edema can occasionally be a cause of bronchial hyperresponsiveness.

In subjects with mild COPD, "percent emphysema and the severity of airflow obstruction were associated with significant decrements in left ventricular filling and cardiac output," the study concluded.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

January 20, 2010

Related Reading

High-resolution CT reveals bronchial wall changes in asthma, December 22, 2009

Childhood smoking exposure linked to early emphysema later in life, May 21, 2009

Pulmonary embolism prevalent in COPD flare-ups, March 10, 2009

CT protocols reduce risk for pulmonary embolism, March 9, 2009

CT recommended to assess bone loss and lung involvement in COPD, December 19, 2008

Copyright © 2010 AuntMinnie.com