"Our findings suggest that playing contact sports may lead to subtle subclinical changes in the athletes' brains," said lead author Alexander Rauscher, PhD, an assistant professor at the university's MRI Research Center.

Rauscher and colleagues prospectively investigated brain volume changes, white-matter hyperintensities (which are linked with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease), and microbleeds among 45 male and female university ice hockey players. They compared the results with those of 15 age-matched control subjects.

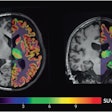

The subjects underwent 3-tesla MRI scans and neuropsychological testing at the start and the end of the hockey season. Athletes who were diagnosed with concussions during that time received additional MR imaging and neuropsychological testing at 72 hours, two weeks, and two months after their injury.

Brain volume had decreased by 0.32% at the end of the hockey season, compared with baseline scans, and by 0.26% in athletes with concussions, the researchers found. Two months after the concussion, brain volume was reduced by 0.23%. Interestingly, there were no significant brain volume changes among concussed athletes 72 hours and two weeks after their injury or in the control group.

MRI is the best modality for this type of investigation because it is "much more sensitive to the subtle changes due to mild traumatic brain injury than other imaging modalities," Rauscher said. "CT is not able to detect these [changes], even at a group level."

The group hopes to continue the research, pending additional funding.

"MRI is expensive and a serial and prospective study that follows athletes over several years requires a lot of MRI scans," Rauscher said. "We think it is worth the cost and effort because the most exciting aspect of such a study is that we can compare the human brain before and after injury, as well as assess the potential of recovery with cessation of activity."