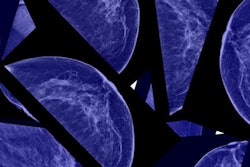

About 15% of cancers detected on breast screening exams represent overdiagnosis and would never represent a health threat to women. The rate is half that of widely cited estimates, according to research published February 28 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

In a study population of 36,000 women ages 50 to 74 who received biennial screening, about one in seven screen-detected cases would be overdiagnosed, according to a team led by Mark Ryser, PhD, from Duke University.

"When it comes to breast cancer screening, it is important for radiologists and their patients to make shared and informed decisions that are based on high-quality evidence," Ryser told AuntMinnie.com. "We hope that our overdiagnosis estimate...will reduce uncertainty around the actual frequency of overdiagnosis, and will enable radiologists and their patients to make more informed shared decisions around breast cancer screening, follow-up testing, and treatment."

Overdiagnosis -- defined as the detection of conditions that would never develop into a health risk to the patient -- is one of the main potential harms of mammography screening for breast cancer. Overdiagnosis can add burden on women through unnecessary treatments for detected tumors that may never have progressed or caused harm in a woman's lifetime.

It's not known just how often overdiagnosis occurs. While widely cited estimates point to a 30% risk of overdiagnosis, previous research has found rates that vary from 0% to 54%. The authors of this new study wrote that accurate knowledge of overdiagnosis rates would help support shared decision-making about screening.

Because of this, Ryser and colleagues wanted to develop a more accurate measure of overdiagnosis rates by analyzing data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The cohort used included data from 35,986 women, as well as 82,677 mammograms and 718 breast cancer diagnoses.

The researchers wrote that these women had annual or biennial screening starting at age 50 and continued until 74 years of age or death from a cause unrelated to breast cancer. The authors modeled the competing mortality risk based on a published age-cohort model for a 1971 birth cohort.

They found that among all preclinical cancer cases, 4.5% were estimated to be nonprogressive. The overall predicted overdiagnosis rate among screen-detected cancer cases was 15.4%. That rate increased from 11.5% at the first screen at age 50 to 23.6% at the last screen at age 74.

The team also found that switching from biennial to annual screening resulted in a predicted overdiagnosis rate of 14.6% annually. Patterns for both screening frequencies were similar, the group wrote.

"We have long known that the most prominent estimates of breast cancer overdiagnosis in the U.S. were inflated," Ryser said. "We were actually not surprised that our number was lower than previous estimates."

Ryser et al concluded that they hope their findings will help experts reach a consensus estimate and help with decision-making about mammography screening.

Ryser told AuntMinnie.com that the team next wants to learn how much healthier breast screening participants at different ages are relative to the general population. He said this will help further measure overdiagnosis rates and personalize a woman’s overdiagnosis risk.

“Ultimately we hope to produce a calculator for women who have been screen-detected so that they can project their risk of overdiagnosis given their age, health status, and other characteristics such as their race and breast density,” he added.

In an invited commentary piece, Dr. Felippe Marcondes and Dr. Katrina Armstrong from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston wrote that healthcare providers should communicate relative and absolute risk estimates of mammography screening.

"Given that approximately seven in 1,000 women will be diagnosed with invasive or noninvasive breast cancer on the basis of a screening mammogram, women should be told that approximately one in 1,000 women who undergo mammography will be found to have a cancer that would never have caused problems," they wrote.

They also added that eliminating overdiagnosis could spare about 25,000 women per year the burden of unnecessary treatment. This is assuming that 60% of the 280,000 breast cancer cases are diagnosed in the U.S. annually through mammography screening.