SAN DIEGO - Researchers from Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit have found that magnetoencephalography (MEG) imaging can help doctors locate -- and possibly treat -- the part of the brain repsonsible for the mysterious ringing in the ears known as tinnitus.

"While other imaging modalities such as PET and functional MRI [fMRI] indicate general areas in the brain that tinnitus activates, MEG pinpoints that area much better," said Dr. Michael Seidman, director of the division of otologic-neurotologic surgery in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit.

"I make the analogy that PET and fMRI light up an area the size of the state of Michigan, whereas MEG isolates it to a street corner in Detroit," he said, in explaining his presentation at the International Tinnitus Forum, conducted in conjunction with the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) Foundation annual meeting.

In his study, Seidman suggested that using noninvasive MEG might aid in diagnosing tinnitus and may detect a reduction in symptoms after different treatments, offering hope to the more than 50 million patients with tinnitus. The imaging technique may also allow physicians to target specific brain regions with electrical or chemical therapies to lessen symptoms, he said.

In fact, Seidman has implanted electrodes designed to interfere with the ringing sound into the brains of six patients with debilitating tinnitus, and four of the cases have registered improvement. Cranial surgery failed to help the other two individuals, but the procedure did not worsen their condition, he said. Additional work in electrical pulse mechanics might improve outcomes.

Seidman also suggested that MEG technology could be used to determine if drugs such as intravenous lidocaine could be administered more directly to the source of the tinnitus, along with evaluating the effects of those medications.

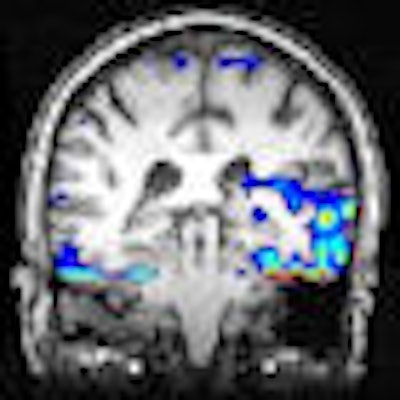

"Since MEG can detect brain activity occurring at each instant in time, we are able to detect brain activity involved in the network or flow of information across the brain over a 10-minute time interval," said co-author Susan Bowyer, Ph.D., bioscientific senior researcher in the department of neurology at Henry Ford Hospital. "Using magnetoencephalography, we can actually see the areas in the brain that are generating the patient's tinnitus, which allows us to target it and treat it."

|

| MEG coherence mapping image overlaid on MRI scan in patient with unilateral tinnitus shows left auditory cortex is significantly more active. |

"Tinnitus is a very perplexing problem. Basically, it is the perception of sound when there is no sound," said Dr. Barry Hirsch, professor of otolaryngology and neurological surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Hirsch said some people are so disturbed by tinnitus that they will undergo surgery to try and control it, often in vain. "What is exciting about Dr. Seidman's work is the possibility that we can identify where tinnitus occurs in individuals," he said. "If we can do that, it may be possible to intervene. The use of MEG is a promising tool, but we need further studies to determine its potential."

MEG measures the very small magnetic fields generated by intracellular electrical currents in the neurons of the brain. Only 20 sites in the U.S., including Henry Ford, are equipped with a magnetoencephalography scanner.

In the study, the researchers analyzed magnetoencephalography scans from 17 patients with tinnitus and 10 patients without tinnitus. In tinnitus patients who have ringing in one ear, MEG detected the greatest amount of activity in the auditory cortex on the opposite site of the brain from their perceived tinnitus.

For patients with ringing in the head or both ears, MEG revealed activity in both hemispheres of the brain, with greater activity appearing in the opposite side of the brain of the strongest perception of tinnitus.

Patients without tinnitus had multiple small active areas in the brain, but no particular areas were found to be highly coherent during the 10-minute MEG scan.

By Edward Susman

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

October 6, 2009

MEG reveals sound processing delays in autistic children, December 2, 2008

Study sheds light on parental instinct, February 28, 2008

Copyright © 2009 AuntMinnie.com