In a study with important implications for both public health and the practice of radiology, CT will soon get its chance to go head-to-head with x-ray for lung cancer screening. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) held a teleconference Wednesday to promote the launch of its National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), an eight-year, multicenter randomized trial designed to compare the efficacy of the two modalities for preventing lung cancer deaths.

Outlining the goals of the trial, co-principal researcher John Gohagan, Ph.D., chief of early detection research for NCI, said the study is especially important due to the persistent high prevalence of lung cancer in the U.S., nearly all of which occurs in a population of about 90 million current and former smokers.

"The death rates for lung cancer have remained high, and not declined like some of the other cancers have," Gohagan said. "We estimate that about 169,000 men and women will be diagnosed with lung cancer (this year), and about 150,000 deaths will occur. We don't have any accepted, proven screening tests for lung cancer, which we believe will reduce the mortality rate, except for the ones we're testing. And spiral CT ... has been shown by other investigators to be very important as a possible screening tool for lung cancer."

Co-principal investigator Dr. Denise Aberle, chief of thoracic imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles explained the methodology of the trial. Over three years, 50,000 smokers or former smokers aged 55 to 74 will be screened at 30 centers located throughout the U.S. Participants will be randomly selected to undergo either a standard chest x-ray or chest CT annually for three years, with analysis and follow-up continuing until 2010. The study will cost $200 million over 8 years.

The number of lung cancer cases and deaths in each arm of the study will be carefully monitored year by year, she said, and because the randomized groups will have equivalent risks, any differences between CT and x-ray in lung cancer deaths will have high validity.

The most important goal will be to measure any differences between CT and chest x-ray in preventing lung cancer deaths, but the study will also analyze the data to assess a number of other factors, Aberle said.

"These include, for example, the impact of screening on smoking behaviors for those individuals who will be continuing to smoke during the trial, the emotional impact of the screening process, the emotional impact of a positive screen, particularly in individuals whose screening test proves to be a false alarm, the costs of screening, and the kinds of medical tests that are associated with screening," she said.

Besides monitoring lung cancer deaths, the data will be extrapolated to the extent possible to examine mortality from all causes, she said. The length of the trial, 8 years, was necessary to overcome the lead-time bias that occurs in all screening studies.

Lead-time bias concerns the difference between mortality, or lifespan, and survival, which measures how long a subject lives following diagnosis, Aberle said. Any screening test improves survival because it advances the date of diagnosis, but doesn't necessarily reduce mortality. The prolongation of survival inherent in screening studies is the reason why effective screening trials need to span several years to ensure accuracy. In addition to lead-time biases, there are also length and overdiagnosis biases that can skew a study's results, she added.

To date, three major lung cancer trials have been conducted in the U.S., but none have answered the key question of which modality is more effective in preventing lung cancer deaths, according to Gohagan.

During the 1970s, the Mayo Lung Project compared the efficacy of chest x-ray screening with sputum cytology for the detection of lung cancer. It concluded that neither technique produced a reduction in lung cancer mortality. However, subsequent analysis of the data concluded that the database was simply to small to produce meaningful results, especially since the trial was designed to detect large differences in the effectiveness of the two exams, Gohagan said (Mayo Clinic Proceedings, September 1981, Vol. 56:9, pp. 544-55).

Beginning in the early 1990s, a second trial, known as the PLCO (Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening trial), evaluated 150,000 men and women randomly for four types of cancer. Designed to evaluate improvements in survival as small as 20%, the trial effectively compared the efficacy of the chest x-ray compared to no screening. However, until now, no large trial has assessed x-ray vs. CT for a reduction in lung cancer deaths, Gohagan said.

The current trial is looking for an improvement in CT over the chest x-ray in terms of reduced lung cancer mortality, he said. If it turns out that there is no mortality reduction with CT, then the NLST trial will effectively be comparing spiral CT to usual care.

Chest x-ray will probably turn out to produce no reduction in lung cancer deaths, he said. But if the PLCO trial does show a positive effect from x-ray, "and it turns out that spiral CT is found to be more effective than chest x-ray in the NLST trial, then we know that we have a very effective spiral CT screening procedure," he said.

Still, because the trial is designed to detect even small improvements in survival owing to the use of CT rather than x-ray, even a minor detected improvement is expected to be valid. And if CT does end up reducing lung cancer deaths significantly, the results will be available well before the trial is completed.

"If there's a 50% improvement (with CT), we'll get the answer more quickly -- maybe within 5 years," Gohagan said.

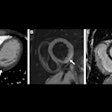

CT participants will undergo a low-dose chest CT screening protocol, using scanners from various manufacturers equipped with four or more detector rows, according to UCLA's Aberle. The radiation dose will be approximately equivalent to a year's normal background exposure.

A particularly important goal that the NCI has recognized for this trial will be a collection of specimens at the time of each screening, Aberle said. Blood, sputum, and urine will be collected from some participants at each annual screening test. The specimens will be placed in a specimen bank for future testing.

"As we learn more about the molecular events and the genetics of lung cancer, these specimens will be used to help identify biomarkers of lung cancer that can help to predict who is at highest risk of lung cancer, or who may have a precancerous condition," she said.

Screening is free of charge. Individuals interested in participating in the trial can sign up by calling 1-800-4CANCER from within the U.S. Recruitment will continue for the next year or two, so applicants who get a busy signal are encouraged to try again.

"An important point to be made is that, regardless of the outcome of the trial, we have the potential to save lives," said John Seffrin, Ph.D., CEO of the American Cancer Society.

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 19, 2002

Related Reading

Half-dose chest CT produces acceptable image quality, August 5, 2002

Spiral CT promising for lung cancer screening, August 2, 2002

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com