Imaging evaluation of the large intestine has undergone remarkable advances over the past decade, particularly with the advent of CT colonography (CTC, also referred to as virtual colonoscopy). Optical colonoscopy (also referred to as conventional or invasive colonoscopy) and CTC allow for complementary diagnostic evaluation of the colonic mucosa. Optical colonoscopy remains the therapeutic gold standard for nonsurgical interventions, whereas the role of CTC in colorectal cancer screening will likely continue to expand.

Cross-sectional imaging modalities such as routine CT also provide for submucosal and extracolonic investigation, including evaluation of the vermiform appendix. Although the role of the barium enema (BE) for colorectal disease continues to wane as alternative modalities evolve, its demonstration of various disease entities remains instructive. The material presented in this chapter covers the broad topics of colorectal polyps, invasive carcinoma, colitis, diverticular disease, and the appendix, in addition to a variety of other colorectal conditions.

1. COLORECTAL POLYPS AND MASSES

A colorectal polyp represents any abnormal protrusion from the bowel wall into the lumen. Broad polyp categories include mucosal-based lesions (neoplastic and non-neoplastic) and submucosal lesions that originate deep to the mucosal surface.

The most important colorectal mass is primary adenocarcinoma. Despite the fact that most colorectal adenocarcinomas are considered to be readily preventable through routine screening and that early detection markedly improves survival, it remains the second-leading cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States, primarily owing to poor screening compliance.

Radiologic and endoscopic studies play a vital role in cancer detection, staging, and monitoring response to therapy. CTC is a rapidly evolving method for colorectal evaluation that complements the established technique of optical colonoscopy. A variety of CTC tools will be presented that are aimed at increasing accuracy and efficiency of interpretation. A number of diagnostic pitfalls at CTC are also discussed.

1.1 Benign Mucosal Neoplasms

CLINICAL FEATURES

• Over 95% of invasive colorectal cancers are believed to develop slowly from benign adenomatous precursors (adenoma-carcinoma sequence).

• Removal of adenomatous polyps, in particular advanced adenomas, interrupts the progression to carcinoma and is the rationale for screening.

• The clinical relevance of neoplastic polyps strongly correlates with lesion size and histology.

• Adenoma histology is as follows: tubular (80%-85%), tubulovillous (10%-15%), and villous (<5%).

• “Advanced adenomas” are defined as ≥10 mm or demonstrating a prominent villous component or high-grade dysplasia; these lesions are the primary target for screening.

• Malignant polyps are rare among the asymptomatic average-risk screening population; subcentimeter adenomas harbor cancer in 0.1% of cases.

• Tubular adenomas account for 30% to 40% of diminutive colonic polyps (≤5 mm); the vast majority do not progress to advanced neoplasia.

• Flat aggressive adenomas appear to be rare in the United States (particularly the “depressed” adenoma).

• Serrated adenomas represent an uncommon but distinct histopathologic subset that demonstrate features of both adenomas and hyperplastic polyps.

• Innumerable neoplastic polyps suggests familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), especially in the setting of a positive family history or suggestive extracolonic findings.

IMAGING FEATURES

• In general, polyps can have a sessile, pedunculated, or flat morphology.

• Adenomas are composed of soft tissue at CTC and may appear erythematous or have a “cerebriform” pit pattern at colonoscopy; however, neither study can reliably distinguish adenomas from hyperplastic or other polyps.

• Tubulovillous and villous adenomas are typically larger than tubular adenomas and are often pedunculated; some villous tumors form “carpet lesions” that cover a relatively large surface area.

• The presence of high-grade dysplasia or malignancy cannot be reliably predicted from the radiologic or endoscopic appearance; thus, large lesions (≤1 cm) generally require histologic evaluation.

• Medium-sized polyps (6-9 mm) represent a relatively low-risk finding; current management of CTC-detected medium-sized lesions consists of CTC surveillance or optical colonoscopy referral for polypectomy.

• Diminutive polyps (≤5 mm) have questionable clinical significance and should not be reported at CTC, despite the fact that up to 30% to 40% may be adenomatous.

FIGURES

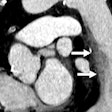

Figure 1.1.1 Sessile tubular adenomas.

Figure 1.1.2 Sessile advanced adenomas.

Figure 1.1.3 Pedunculated advanced adenomas.

Figure 1.1.5 Villous adenomas.

Figure 1.1.6 Serrated adenoma.

Figure 1.1.7 Familial adenomatous polyposis.

Figure 2.1.1 Mild ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.1.2 Moderately active ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.1.3 Severe ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.1.4 Colonic perforation from toxic ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.1.5 Long-standing ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.1.6 Dysplasia and carcinoma in long-standing ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2.1.7 Rectal fistulas complicating ulcerative colitis.

Copyright © 2007 by Saunders, an imprint of Elsevier, Inc.