A 1987 study that stratified trauma patients by risk of intracranial injury apparently works as well for CT as it did for x-ray. In fact, new research concludes that the old Masters guidelines choose patients for head CT far more reliably than the emergency room physicians treating them.

Dr. Jamie Mangin from the Hamilton General Hospital trauma center in Ontario, Canada, reviewed the 1987 work, and offered an enlightening new study at 2001 American Roentgen Ray Society meeting in Seattle.

"In 1987 Masters [SJ, McClean PM, Arcarese JS et al] published a paper that used clinical selection criteria they developed to stratify patients into risk among low, moderate, and high risk of intracranial injury," Mangin said (New England Journal of Medicine, January 8, 1987, Vol.316:2, pp. 84-91).

"We decided in our study to apply those criteria to the use of CT in minor head trauma, and see if we could reduce the number of CT exams we performed. The other question we wanted to answer is [whether] the emergency doctor's initial impression correlates with the CT results," he said.

The 1987 study assembled a multidisciplinary panel of experts to review skull x-rays of 7,035 patients from 31 hospitals. Follow-up data obtained in 4,931 patients found no intracranial injuries among 3,531 patients deemed to be at low risk. Statistical analysis estimated a worst-case scenario of only 8.5 intracranial injuries out of 10,000 patients deemed low-risk, confirming the validity of the results, Mangin said.

The Hamilton study prospectively evaluated 178 consecutive patients with sustained head trauma who also underwent CT of the head, as ordered by the attending emergency room physician [ERP]. The ERPs were asked to complete a questionnaire on each patient prior to imaging.

The questionnaire gathered data on patient demographics and the mechanism of injury, and asked whether there was a loss of consciousness, amnesia, previous head injury, substance use, medical status changes, focal neurologic deficits, and signs of external or other injuries. Based on their answers to the questionnaire, patients were deemed to be at low, medium, or high risk of intracranial injury based on the following Masters' clinical criteria:

Twenty-two patients were found to be at low risk:

- Asymptomatic

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Scalp hematoma

- Scalp laceration

- Scalp contusion or abrasion

- Absence of moderate or high-risk criteria

One hundred thirteen patients were deemed to be at moderate risk:

- Change of consciousness

- Progressive headache

- Alcohol or drug intoxication

- Unreliable or inadequate history of injury

- Age less than 2 years (unless injury was very trivial)

- Post-traumatic seizure

- Vomiting

- Post-traumatic amnesia

- Multiple traumas

- Serious facial injury or signs of basilar fracture

- Possible skull penetration or depressed fracture

- Suspected physical child abuse

And 42 patients had one or more symptoms that put them at high risk:

- Depressed level of consciousness not clearly due to alcohol, drugs, metabolic causes

- Focal neurologic signs

- Decreasing level of consciousness

- Penetrating skull injury or palpable depressed fracture

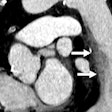

"We had 22 patients who ended up in the low-risk category, 11 females and 11 males," Mangin said. "We had 21 normal CTs in low risk, and one abnormal. The abnormal CT showed a small occipital contusion; it had no mass effect and no neurosurgical management." The patient was sent home.

Telephone follow-up of all 22 low-risk patients at 2-4 months revealed no clinical sequelae, except for 7 patients with transient headaches that did not affect functioning, and which disappeared within a few days.

The other question the study posed was the extent to which the ERPs' impressions correlated with post-CT results. "There was no correlation at all," Mangin said. While 21 of the 22 low-risk patients had normal CT scans, the cautious ERPs had suspected 8 contusions, 9 subdural hematomas, and 7 normal patients in the same group.

"In conclusion, we feel that the Masters clinical criteria accurately selects patients with low risk of intracranial injury, resulting in no clinically significant sequelae, and therefore this group of patients did not require CT of the head," he said. "In the second question, we found no correlation between the preliminary impressions and CT results."

An audience member wanted to know how they managed to get the ERPs to complete the questionnaire for every patient.

"Yeah, well, we forced them," Mangin said. "They couldn't have the CT until they filled out the form. They were quite happy when the study ended."

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

May 29, 2001

Click here to post your comments about this story. Please include the headline of the article in your message.

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com