Hoping to detect Alzheimer’s disease before the onset of irreversible dementia, researchers are using MRI and PET to identify brain changes that precede clinical symptoms of the disease by several years.

And while it’s too early to tell if one or both modalities will win the trust of referring physicians and insurance companies, the competition is good news for the 12 million people worldwide who suffer from Alzheimer’s, a number that's predicted to swell to 22 million by 2025.

There is no cure for Alzheimer's, but there is hope in the form of several drugs, now in clinical trials, that are designed to slow disease progression. That’s where imaging comes in: It can identify the anatomic and metabolic changes that precede dementia, prompting physicians to administer early drug therapy, and possibly even averting clinical symptoms altogether.

"Catching Alzheimer’s early is more important than ever because of exciting treatments in the offing," said Dr. Clifford Jack, professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.

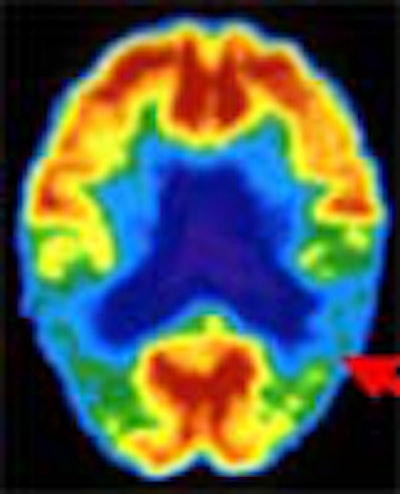

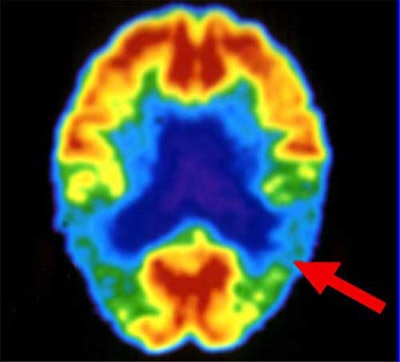

Jack joins a growing number of radiologists who believe they will someday screen for the disease in elderly people with memory loss or a family history of Alzheimer's. But consensus stops at the choice of modality. Some favor FDG-PET, which detects Alzheimer’s based on metabolic anomalies. Others favor MRI, either structural, which targets anatomic changes in the brain; or functional, which homes in on telltale brain activation patterns.

Both modalities show promise, but both have disadvantages. PET is expensive and not widely available. Structural MRI requires time-consuming post-processing work. And functional MR requires a high-field magnet. Despite their shortcomings, however, PET and MRI are giving researchers a 10-year jump on the detection of pathology.

Using MR spectroscopy, Jack and colleagues pinpointed one of the first chemical changes in the brain that indicates Alzheimer’s, according to a study published in the July 2000 issue of Neurology. The team imaged people with normal cognitive function, as well as patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s.

Because a large percentage of MCI patients develop Alzheimer’s in 5-10 years, the researchers reasoned that if they identified a marker that differentiates MCI patients from healthy people, the same marker would likely signal the early onset of Alzheimer’s.

The Mayo study measured a brain metabolite known as myoinositol (mI) that is elevated in patients with MCI and Alzheimer’s. Prior to this study, researchers believed that depressed N-acetylaspartate (NAA) levels were the first biochemical indicator of Alzheimer’s, but Jack found that NAA levels were not depressed in MCI patients.

This means that the first significant chemical alteration of Alzheimer's is raised mI levels -- a byproduct of neural inflammation caused by plaque buildup -- with lowered NAA levels occurring next, he wrote.

This test can augment another MRI exam that measures atrophy-induced shrinkage of the hippocampus, another Alzheimer’s indication.

"With one $400 scan, we could obtain two independent measurements that assess the likelihood someone will develop Alzheimer’s," Jack wrote. "We could screen elderly people in whom there is a question of cognitive decline."

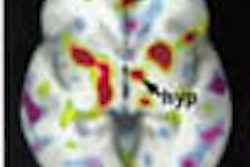

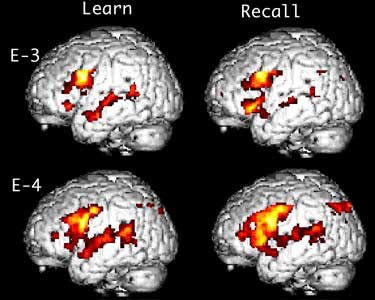

Other MRI-based research focuses on how the brain adapts to neural degeneration. Using functional MRI, UCLA researchers imaged 30 cognitively normal subjects -- half of whom were carriers of the APOE-epsilon-4 allele that places them at genetic risk of Alzheimer’s -- while they underwent a memory recall test. Subjects with the at-risk allele had increased blood flow to the hippocampus, according to a study published in the August 17, 2000 New England Journal of Medicine.

"The brain is compensating for the early stages of Alzheimer’s by firing its neurons more, which increases blood flow to that area," wrote Dr. Susan Bookheimer, associate professor of psychiatry and biobehaviorial sciences at UCLA.

In a two-year follow-up, the subjects went through the same MRI scan and memory test. Patients who had the highest degree of brain activation two years prior exhibited the greatest degree of memory loss.

"This means the brain changes before there’s memory loss," she said. "Functional MRI could screen people with a strong family history."

Comparison of two cognitively normal patients undergoing fMRI exams. The patient with the APOE-epsilon-4 allele (E-4), which places him at increased risk of Alzheimer's, shows increased brain activation during memory recall.

But despite MRI’s promise, critics charge that the data just isn’t there yet.

"Functional MRI of dementia is only a few years old, while we’ve been doing FDG-PET on Alzheimer’s since 1980," said Dr. Daniel Silverman, head of UCLA’s neuronuclear imaging research group.

Growing support for PET

With 20 years of research to draw from, PET researchers are beginning to publish some convincing numbers. In a study presented at last year’s Society of Nuclear Medicine meeting, UCLA's Silverman and colleagues compared the results of 70 PET scans with autopsy-confirmed diagnoses. PET’s sensitivity in confirming Alzheimer’s was 96%.

In another study published in the November Journal of Nuclear Medicine, researchers from the National Cancer Institute found that PET is highly accurate in determining whether a patient’s dementia is caused by Alzheimer’s, or another illness. And in an intriguing study, Silverman’s group found that the metabolic decline associated with Alzheimer’s might begin as early as 20 years of age.

Because PET can also monitor the effectiveness of enzyme-inhibiting drugs, it may also help expedite several ongoing clinical trials.

"PET reveals how well treatment works," said Dr. David Kuhl, chief of nuclear medicine at the University of Michigan and a PET pioneer. "A popular anticholinesterase agent, donepezil, is reported to decrease enzymes by almost 100%, but we’ve shown an inhibition rate of only 25%."

PET critics, however, contend that MRI provides more detailed pictures in less time, and without radiation exposure. Another drawback, according to Bookheimer of UCLA, is that PET scans are conducted only when the patient is at rest, so it can’t image the brain while it is adapting to Alzheimer’s but before memory loss occurs, unlike functional MRI. By the time PET images reveal neural decline, it may be too late, she wrote.

Then there’s availability and cost. There are only about 200 PET systems in clinical use in the U.S., and the typical scan costs more than $1,000.

Silverman defended the high price of PET, noting that in some cases it’s comparable to an MRI study. He also cited the technology's long-term cost savings: The quicker Alzheimer’s is diagnosed with PET, the sooner the patient receives drug therapy, and the less time the patient spends in expensive nursing homes.

In addition, a doctor may suspect a patient has Alzheimer’s and, to be safe, prescribes one year of donepezil at $1,800, a treatment regimen that is more expensive than an FDG-PET exam that could rule out Alzheimer’s.

As for availability, Silverman said that the number of PET scans and scanners has increased significantly in recent years.

"Within five years all hospitals with nuclear imaging departments will have some kind of coincidence imaging technique suitable for FDG imaging," he predicted.

Finally, Silverman said that the success of a PET-based Alzheimer’s imaging exam hinges on higher Medicare reimbursement as well as further research. And higher payments aren't far-fetched, given HCFA’s December 15 decision to provide coverage of PET imaging for six types of cancer.

"HCFA may decide this year to reimburse PET imaging for dementia, which will be a huge boost," Silverman said.

Regardless of which modality pans out as the better way to detect early Alzheimer’s, the Mayo Clinic's Jack cautioned that the role of imaging will be to predict rather than diagnose the disease.

"Imaging could be a useful component, but it will never replace a good neurological exam," he said.

By Dan KrotzAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

January 22, 2001

Related Reading

HCFA broadens Medicare coverage for PET, December 18, 2000

FDG-PET clears up metabolic murkiness between dementia and Alzheimer's, November 7, 2000

Adding SPECT, MRI to Alzheimer's work-up costs more than it's worth, analysts say, October 11, 2000

MRI measures can predict Alzheimer's disease, March 31, 2000

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com