CANCÚN, MEXICO - For better or worse, the critical fallout from two New York Times stories last week has drawn enormous attention to mammography. Over the past few days, controversy has clouded the procedure like a bad diagnosis, while the public has been treated to widely divergent views of what mammography can and cannot do.

In short, it is a perfect time for a tour of mammographically discovered lesions. At the 2002 International Congress of Radiology, the guide was Dr. Edward Sickles, mammography section chief of the University of California, San Francisco.

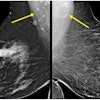

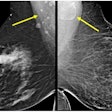

For palpable lesions, tiny lesions, and those in between, the diagnosis of breast cancer nearly always begins with the discovery of a mass in mammography, Sickles said in a presentation Tuesday. Perhaps more to the point for mammography, a mass is a 3-D volumetric lesion visible on two different mammographic projections, he added. The structures may be rounded or oval, with generally convex outward contours, and are denser at the center than the periphery, but the mass is where it all begins.

"It is extremely important for the radiologist who is interpreting mammograms to know what the mammographic features of breast cancer are when they present as masses," Sickles said. The million-dollar question, of course, is whether the mass is benign or malignant.

"In the best of all possible worlds, we would be able to separate all malignant from benign masses, and we could simply make a radiologic diagnosis and go to treatment," he said. "Unfortunately, mammography is not that accurate. It's quite sensitive in identifying lesions that are suspicious for malignancy, but it is not very accurate in identifying which lesions are absolutely benign."

Thus, the goal of the talk was to point out the few instances in which a mass was almost certainly benign, the few instances in which it was almost certainly malignant, and the more common "suspicious" zone, where additional imaging or diagnostic modalities are required for diagnosis.

Size doesn't matter

The size of a mass gets a lot of discussion, but has no value whatsoever in predicting whether a mass is benign or malignant, Sickles said. Size does affect the clinical management of the mass, because the larger that masses become, the more they tend to be found during examination, and as a result are often biopsied. But the decision to biopsy has nothing to do with the mammographic features, but rather how the mass is found, Sickles said.

Location isn't everything

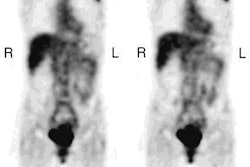

As for the location of the mass, 15% of breast cancers are found in the upper inner quadrant, 45% in the upper outer quadrant, 10% in the lower outer quadrant and 5% in the lower inner quadrant, with the remaining 25% of cancers found in a circular area right in the center of the four quadrants, he said.

But the funny thing is, the distribution of benign lesions is precisely the same in all five areas. Thus, location is "no help in determining whether the mass is benign or malignant," Sickles said. That is, except for the exception.

"If you can prove at imaging that what looks like a mass in mammography is actually located within the skin, and some skin lesions are apparent at mammography, then you know it's not breast cancer," he said.

That's because breast cancer doesn't arise on the surface, but rather from deeper in the organ parenchyma, Sickles said. When the distance to the skin is not entirely clear, acquiring another image from an angle tangential to the mass, with a metal marker such as a BB on the skin, can generally clarify matters.

"Most of these lesions turn out to be sebaceous cysts, but it doesn't really matter what it is. It's benign, and if there are no symptoms, nothing has to be done," he said.

Fat is good…

Masses can contain fat, which is dark on mammograms, or fibroglandular tissue, which is white on mammograms, or a mixture of both, known as fibroadenomas or hamartomas. Since breast cancer arises from fibroglandular tissue, any mass that contains fat, or a mixture of fat and fibroglandular tissue, is benign and doesn't need biopsy.

Fatty masses within fatty breast tissue are uniformly dark, and thus difficult to distinguish. It is only by identifying the very thin fibrous pseudocapsule surrounding the mass that such masses can be distinguished, Sickles said, but again it doesn't matter because the mass is benign. When the mass is palpable, good image quality, or techniques such as spot compression or spot compression magnification views, are sometimes needed to see the thin pseudocapsule, and thus prove the mass is benign.

"In general, if you have a single fat-containing mass it's a lipoma, and if you have more than one, or even just one very small mass, chances are you're dealing with fat necrosis," which generally indicates antecendent trauma, according to Sickles.

A third type of fat-containing mass is a galactocele, which always indicates a recent history of nursing. Thus, fat-containing masses can usually be distinguished by their mammographic appearance, combined with a simple medical history. Lipofibroadenomas or hamartomas contain a mixture of fibrous and fatty and adenomatous tissue.

Another type of fat-containing mass is the intramammary lymph node. They are so common as to be mammographically visible in about 10%-15% of women. They are typically seen in the outer half of the upper-outer quadrant. The closer they are to the axilla the larger they grow, and are likelier to be palpable.

Mammographically, such masses have circumscribed margins, are oval in shape, adjacent to a blood vessel. Ordinarily, fatty replacement of the hilar region of the node should also be visible at the periphery of the mass, Sickles said.

…so is compression

Size for size, breast cancers tend to look whiter on mammography than their benign counterparts. The phenomenon has nothing to do with the relative linear attenuation of the two types of mass, but is rather an artifact resulting from uniform thickness compression. Benign masses tend to flatten out, while breast cancers, which tend to have a desmoplastic reaction to compression, tend to resist compression and remain thicker, and whiter, on mammography. Without overdoing it, vigorous breast compression is required during imaging in order to use opacity as a determining factor in malignancy.

Shape and margin

The very subtlest distinctions in mammography relate to shape and margin, Sickles said. So in an effort to put mammographic reports on an even playing field, linguistically speaking, the BI-RADS definitions of shape and margin were created in the U.S., and are increasingly accepted worldwide.

"Round is like a circle, oval is in the shape of an ellipse, lobular is basically oval with a few gentle undulations to the contour, irregular is anything other than the first three," Sickles said. The first three strongly suggest that the lesion is benign, while the fourth raises a suspicion of malignancy.

"Margins can be circumscribed, which means well defined, they can be microlobulated, which means they have very small undulations throughout the contour," as if x-raying a blackberry, he said. "Obscured" means that some margins of the mass are immediately adjacent to fibroglandular tissue that is as dense as the mass itself, or isodense, creating a silhouette that obscures part of the mass. Different imaging techniques, angles, and compression levels can be used to "unobscure" obscurities, and, for that matter, render indistinct margins distinct.

"'Indistinct' ... implies that you're not seeing the margins of the mass because they're adjacent to fatty tissue, and that the margins are inherently poorly defined," Sickles said. "This implies that there may be some infiltration of the margins of the mass into the surrounding fat, and thus (there is) a suspicion of malignancy."

Spiculated masses are characterized by fine white lines radiating out from the borders, a feature that also implies a suspicion of malignancy. More commonly, however, the white lines indicate a desmoplastic reaction around the mass, and the white lines demonstrate fibrosis.

Among the shapes, circumscribed implies benign, while spiculated, indistinct and microlobulated are all suspicious. "Obscured" suggests that more information is needed to characterize the mass, Sickles said.

Unfortunately, many masses confound simple definition. A mass may have both circumscribed and obscured margins, or both lobular and irregular margins. What to do with mixed signals?

"You act on the most suspicious imaging finding," he said.

But simplicity is elusive. When the margins appear obscured, but are mostly circumscribed, the radiologist assumes a working diagnosis that the lesion is likely benign, Sickles said. In such cases, ultrasound can be used to confirm the circumscribed margins, or detect sharp contours suggestive of malignancy. The latter case should be followed up with biopsy. Circumscribed margins confirmed on ultrasound can simply be followed up and observed for stability.

"How do we identify a mass? We start out by identifying the typically benign ones. If we can show that a mass is in the skin, it's benign. If we can show a mass contains fat, it's benign," Sickles said. "If the mass has features that suggest it's benign, we do ultrasound. And if ultrasound shows that it's a cyst, it's benign. That's as far as we can go with imaging."

The rest of the masses are either suspicious, or so likely benign that they call for the more complicated choice of following up, Sickles said. This decision depends on the characteristics of the mass, both currently, and compared with prior imaging if possible.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 3, 2002

Related Reading

ACR blasts New York Times mammography articles, July 1, 2002

Mammographers question newspaper’s ‘crusade’ against breast imaging, June 28, 2002

New York Times takes mammographers to task, June 27, 2002

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com