MRI studies of amnesic patients are teasing out the pathways of memory, researchers said at the 2003 Rotman Research Institute conference in Toronto. An investigator from Rotman compared the brain activity of an amnesic patient, known as KC, with that of a healthy control subject, called PC. Meanwhile, another researcher from Germany sought the brain correlates of functional retrograde amnesia.

KC, a 50-year-old, right-handed man, became an amnesiac after suffering a closed-head injury in 1981; he has severe damage to both sides of his hippocampus. To date, KC is unable to form new memories, and has lost all of his recall of specific events, but he retains extensive semantic memory -- and skills such as the ability to play chess.

More important, KC has good spatial memory of the neighborhood in which he has lived all his life, even though he can remember no specific incident from the area, doctoral student Shayna Rosenbaum told AuntMinnie.com. This conflicts with previous neuroimaging evidence, specifically British research that studied London taxi drivers. Their work showed that the hippocampus is involved in recalling complex routes, Rosenbaum said (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, April 11, 2000, Vol.97:8, pp.4398-4403).

To try to understand the conflict, Rosenbaum and colleagues, recruited PC as the control subject. PC is the same age as KC, also right-handed, and equally familiar with the neighborhood. Both men were presented with a series of six spatial memory tasks while being scanned with 1.5-tesla MR scanner (Signa, GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI).

Rosenbaum said the key finding was that the portion of KC’s hippocampus that remains -- about a quarter of the structure -- was active, but only during tasks in which he was asked to estimate the distance between two landmarks. The same was true for the control subject, she said.

The key differences between the two men were in their use of the retrosplenial cortex (RSPL) and the inferotemporal cortex (IT), she said.

KC’s RSPL was active for all the tasks, while the control subject’s was active only when he was asked to estimate whether a given vector represented the correct direction between two landmarks. The extensive use of the RSPL in the patient KC may be a compensation for structural damage in other areas, Rosenbaum said.

On the other hand, KC’s IT was only active for one of the tasks, while PC’s structure was involved in four -- possibly a sign of reduced function in this area, she said.

The data appears to support the idea that the hippocampus is associated with successful retrieval of spatial knowledge, even in a patient whose hippocampus is severely damaged.

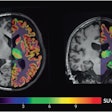

In another study, doctoral student Esther Fujiwara of Germany’s University of Bielefeld used a 1.5-tesla whole-body MR scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) to determine brain correlates of functional retrograde amnesia.

The three patients were a 17-year-old girl, a 33-year-old locksmith, and a 30-year-old engineer. All were right-handed and none had lesions that might account for their memory loss; all of the patients had episodic amnesia for part or all of their previous lives, and two also showed minor semantic deficits, Fujiwara told AuntMinnie.com.

In essence, Fujiwara said, all three patients "have lost their previous lives" for no apparent reason. The lost memories "must be there because there is no structural damage. But for some reason, retrieval is impossible."

In the case of the locksmith, some childhood and early adulthood memories returned within three days of the onset of the amnesia, although he still could not remember anything that had happened in the past 14 years.

To probe the situation, Fujiwara and colleagues scanned the three patients while they were asked to retrieve -- or try to retrieve-- episodes from the amnesic and post-amnesic period. The catch was that some of the episodes in both periods were fictional.

The researchers saw significant increases in neural activity for all true memory conditions, bilaterally in the lateral temporal cortex, the dorsal-occipital cortex extending to the fusiform gyrus, the superior parietal cortex, the cerebellum, and the prefrontal cortex.

All four possibilities were compared with each other in a pair-wise fashion, Fujiwara wrote, but perhaps the most significant result came from seeing what happened when patients tried to recall either true or false events from the amnesiac period.

"Maybe the most interesting result is the absence of differential activity when trying to recall either a true or fictitious episode in the amnesic period," she said.

The patient’s brain did not distinguish between true and false episodes in the blanked-out period, implying that this lack of activity may be what Fujiwara called a "neuronal correlate" of functional retrograde amnesia.

"In the non-amnesic period, they were able to tell the difference (between true and false memories) and we had differential activation patterns," Fujiwara said.

Patients with retrograde amnesia are very rare, and each case is different, Fujiwara said. This is the first fMRI study of more than one patient.

Interestingly, the amnesia may have actually improved life for one of the patients, she said. The 17-year-old girl had been severely depressive for more than a year, but "after the onset of amnesia, she forgot her depression," Fujiwara said.

By Michael SmithAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

April 4, 2003

Related Reading

fMRI reveals secrets of better memory, January 13, 2003

FDG-PET spies early decline in forgetful folks, October 22, 2002

Women, men use different parts of brain to remember, July 24, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com