Ultrasound can be effective for diagnosing, and then treating, a wide range of athletic injuries. Detail and contrast resolution continue to improve along with image quality and accuracy. Injuries ranging from tendinopathy to post-traumatic synovitis, impingement syndrome, and back pain have been successfully managed with ultrasound. At the same time, intervention requires that great care be taken to avoid exacerbating the problem.

Low back pain

A recent study from the University of Innsbruck in Austria found that adolescent elite skiers have an increased risk of having low back pain develop because of high-performance training. The prospective lumbar radiographs of these 120 skiers indicated incidence of anterior end plate lesions, Schmorl's nodes, posterior end plate lesions, spondylolysis, scoliosis, and spina bifida occulta (Clinical Orthopaedics, September 2001, Vol.130, pp. 151-162).

Low back pain also is common among competitive cross-country skiers, according to orthopedic surgeons from Karolinska Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden. For their study, 53 top male and 34 female skiers ages 16-25 were interviewed with a questionnaire regarding anthropometric parameters, training variables, back pain, and other injuries. The frequency of back pain was 64% in the whole group, men affected slightly more often than women, they reported (Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports, February 1996, Vol.6:1, pp. 31-35).

Image-guided intervention

Dr. Wayne Gibbon outlined the indications and interventional techniques applicable to exercise-related injuries at the 2001 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiology meeting in Melbourne, Australia. He also discussed image-guided interventions in athletic injuries. Gibbon is the chairman of medical imaging at the Royal Brisbane Hospital and professor of diagnostic imaging at the University of Queensland, both in Brisbane, Australia.

"The most common indication for sticking needles around diseased tendons relates to the parartenon," he explained. "The major large tendons in the body don’t have a tendon sheath, but they produce a large amount of fibrinous deposits that are creating an inflammatory response around it."

Injecting local anesthetic around the paratenon causes hydrostatic distension, which facilitates breakdown of the fibrinous deposits, Gibbon said. The anesthetic enables physiotherapists to start manipulative treatment that also aims to disrupt fibrinous material.

Is it the paratenon?

"In terms of putting steroid in at the same time, that really is a question of whether there is intratendonous disease present or not. You’ve got to be fairly confident that the primary problem is in the paratenon -- rather than that there is active disease within the tendon itself," he said.

The paratenon is infinitely small, only a few microns thick. Sonographically the parallel mildly echogenic lines that you see at the margins of the tendons aren’t really the paratenon, according Gibbon.

"What you’re actually seeing is almost a sonographic artifact because of the difference in the acoustic impedances between the tendon and adjacent soft tissue, but if you do see contrast enhancement that becomes a slightly different question," he said.

The paratenon is not a closed compartment, and should not be mistakenly thought of as a type of tendon sheath. Gibbon suggested that an MR scan be performed to see whether there is truly intratendon damage, which will determine whether it is safe to inject steroid.

"If there is tendon damage you run the risk of a rotten tendon becoming even more rotten by the steroid reducing the healing response," he said. "There is a balance between reducing inflammatory response, which in itself is producing damage to the tendon, and putting steroids in and stopping that healing response within the tendon, which will then weaken the tendon sufficiently that the tendon will fail."

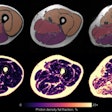

The improved sensitivity of color Doppler has enabled this modality to demonstrate gross dilation of the paratenon vessels. When these paratenon vessels are visualized extending into the tendon, then it is an indication of tendon damage.

Hold the steroids

"If you have that degree of hyperemia within the tendon, I would suggest it is probably not a good idea to put steroid in," he said. Common sites of paratendinitis include the Achilles tendon and the patellar tendon.

Cases of tenosynovitis, when disease is restricted to within the tendon sheath, are a more straightforward situation, according to Gibbon.

"You have to be careful as to what you define as disease within the tendon sheath. Fluid in itself does not indicate that there is a tenosynovitis. If you’ve got a tendon passing a joint and there is fluid inside the joint, then there is in most instances communication within the adjacent tendon sheath as well," he explained.

Just as you get Baker’s cysts forming secondary to a knee joint effusion, you get filling up of the tendon sheath secondary to effusions, particularly inside adjacent joints.

"So you’ve really got to be sure that you’ve seen tendon sheath disease primarily. The only way to do that is looking at whether there is synovial hypertrophy on ultrasound," Gibbon said. Because the phenomena of synovial hypertrophy takes time to develop, he recommended using MR, which will show enhancement of the tendon sheath if disease is present. This represents hyperemia associated with early-stage tenosynovitis.

The juxta-articular tendons at the ankle, the biceps femoris tendon, wrist tendons, and snapping ilio-psoas tendons are common sites for tenosynovitis. The type of sporting activity or overuse phenomena will determine the site of injury.

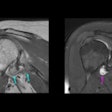

With respect to the biceps tendon in the shoulder, fluid in the tendon sheath is usually a result of joint disease rather than injury to the biceps tendon, he said. Gibbons suggested that when ultrasound demonstrates thickening of the biceps tendon within the sheath, and the patient’s symptoms relate to the bicipital groove, therapeutic treatment is worthwhile.

Remove the bubbles first

The high-resolution linear-array transducers that have been developed for musculosketal ultrasound afford excellent resolution of the needle as it inserted. Because the areas being treated are most often superficial, the angle of the needle is almost perpendicular to the ultrasound beam. This enables good visualization of the needle, because ultrasound is strongly reflected at this angle of incidence. Injecting air obscures the deeper structures, so it is important to remove all of the bubbles from the local anaesthetic before injecting, Gibbon explained.

Injecting steroids is even more difficult. Steroids tend to have a series of microbubbles within the solution, and also have a lot of crystalline deposits within, and they tend to have quite a high degree of reflectivity," he said.

An important limitation of ultrasound is its inability to differentiate between infection and inflammation. According to Gibbon, "injecting steroid into an infected joint and tissue is a disaster." He recommended aspirating an amount of fluid for inspection and analysis. If there is any clinical doubt regarding infection, check the turbidity of the fluid before injecting, he advocated.

A similar treatment philosophy can be applied to bursitis, such as reto-calcaneal, deep pre-tibial, and pes anserinus bursitis. Bursas tend to distend when diseased, so they are particularly good targets for ultrasound-guided therapeutic injections.

Don't aspire to treat muscle hematomas

Gibbon also discussed the problems associated with intramuscular haematoma aspiration, with or without sclerosant injection. Because blood is an excellent culture medium for infective organisms, he suggested that aspirations and injections of muscle hematomas should be avoided. He warned that pyomyositis can be life-threatening, even in the fit young athlete, and to "keep well away."

Gibbon reported that he had an extremely good degree of success using shock-wave therapy in cases of enthesopathy. "Any overuse phenomena is a balance between repetitive minor injury and the body’s ability to repair it. Anything that increases the local blood supply increases the ability of the body to repair that tissue," he said.

By Leanne McKnoultyAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

February 17, 2002

Leanne McKnoulty is an accredited medical sonographer currently lecturing in ultrasound at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She also is an editor at Ultrasound Review.

Copyright © 2002 AuntMinnie.com