Editor's note: As part of the celebration of AuntMinnie.com's upcoming 25th anniversary, we're presenting 25 for 25 -- a series featuring our most popular content for each of the last 25 years. New articles will be published each Monday until our official anniversary at RSNA 2024. As the initial COVID-19 vaccines became available in the second year of the pandemic, reports emerged of imaging findings associated with vaccination. Our most highly read article in 2021 reported on two of these studies.

Researchers are warning that the COVID-19 vaccine can manifest on imaging in ways that appear to be disease, according to two studies published February 24 in the American Journal of Roentgenology and Radiology.

As more people get vaccinated for COVID-19, radiologists must be familiar with how the vaccine may affect imaging results, wrote Shabnam Mortazavi, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles. Mortazavi conducted a study that included data from 23 women who underwent breast imaging after being vaccinated.

"Practice recommendations are needed to prevent excessive follow-up imaging and potential biopsy of COVID-19 associate axillary adenopathy," she noted.

Best practice?

Current recommendations from the Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) for managing unilateral axillary adenopathy on screening exams after COVID-19 vaccination suggest that clinicians categorize these findings as BI-RADS 0 for further follow-up of the ipsilateral breast; after diagnostic workup, conduct a follow-up exam four to 12 weeks after the second vaccine dose; and if adenopathy remains, perform a biopsy. But it isn't clear whether this protocol is really necessary, according to Mortazavi.

Mortazavi and colleagues evaluated data from 23 women who presented with axillary adenopathy on mammography, breast ultrasound, or breast MRI after being vaccinated for COVID-19 between December 2020 and February 2021. Of these, 13% underwent breast imaging because they were symptomatic, while 43% were undergoing screening and 43% were having imaging for other reasons.

The team found that most of the adenopathy on breast imaging occurred with the Pfizer vaccine (52%), among asymptomatic women presenting for either screening or diagnostic purposes (86%), and on ultrasound (52%).

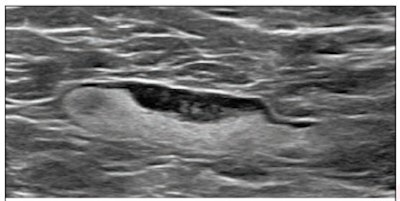

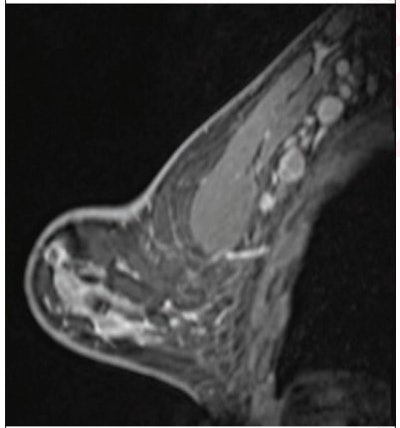

(Above) 55-year-old woman who underwent screening mammogram and ultrasound seven days after first COVID-19 vaccination dose. Screening mammogram and US demonstrated unilateral left axillary lymph node with cortical thickness of 5 mm on ultrasound (not shown). BI-RADS category 0 was assigned. Ultrasound from diagnostic work-up performed seven days later showed no change in lymph node size. BI-RADS 3 was assigned. (Below) 41-year-old woman who underwent high-risk screening breast MRI 15 days after first COVID-19 vaccination dose. Sagittal T1-weighted fat-saturated contrast-enhanced MRI shows extensive unilateral left level I-II axillary adenopathy. BI-RADS 3 was assigned. Images and captions courtesy of the American Roentgen Ray Society.

(Above) 55-year-old woman who underwent screening mammogram and ultrasound seven days after first COVID-19 vaccination dose. Screening mammogram and US demonstrated unilateral left axillary lymph node with cortical thickness of 5 mm on ultrasound (not shown). BI-RADS category 0 was assigned. Ultrasound from diagnostic work-up performed seven days later showed no change in lymph node size. BI-RADS 3 was assigned. (Below) 41-year-old woman who underwent high-risk screening breast MRI 15 days after first COVID-19 vaccination dose. Sagittal T1-weighted fat-saturated contrast-enhanced MRI shows extensive unilateral left level I-II axillary adenopathy. BI-RADS 3 was assigned. Images and captions courtesy of the American Roentgen Ray Society.

"This study highlights axillary adenopathy ipsilateral to the vaccinated arm with Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccine as a potential reactive process with which radiologists must be familiar," Mortazavi concluded. "Incorporating a patient's COVID-19 vaccination history, including vaccination date and laterality, is critical to optimize assessment and management of imaging-detected axillary adenopathy in women with otherwise normal breast imaging."

Vaccine or metastasis?

In a related study in Radiology, a group led by Can Özütemiz, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis presented results from five patients whose imaging showed axillary lymphadenopathy after receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine and which initially prompted concerns of cancer metastasis. The five patients included the following:

- A 32-year-old woman presenting with a neck mass on the left side who underwent ultrasound which showed an indeterminant mass. She had biopsy, staging PET/CT, and started chemotherapy; three-month PET/CT follow-up showed that the mass had resolved. She had received the COVID-19 vaccine six days before the initial PET/CT exam.

- A 57-year-old woman with a family history of breast cancer who underwent annual screening breast MRI. Left axillary lymph nodes were swollen. She had received the COVID-19 vaccine five days before the breast MRI exam; it was recommended that she be followed up with ultrasound in four to six weeks.

- A 41-year-old man with a history of liposarcoma in the left thigh. Follow-up MRI showed new clusters of swollen lymph nodes; he had received his second dose of COVID-19 vaccine four days before the exam and opted for surveillance.

- A 46-year-old woman with history of triple-negative ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) who was treated with double mastectomy. Follow-up chest CT showed swollen lymph nodes; she then underwent PET/CT. She had received the first COVID-19 vaccine dose 15 days before the chest CT and the second dose seven days before the PET/CT. She opted for ultrasound-guided biopsy of the swollen nodes, however.

- A 38-year-old woman with family history of breast cancer evaluated for left breast pain with diagnostic mammography and ultrasound. Ultrasound showed a swollen lymph node; she underwent ultrasound-guided biopsy. She had received the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine eight days before the initial mammogram and the second dose on the day of the biopsy.

"Our findings are important, particularly for cancer patients," Özütemiz and colleagues wrote. "Radiologists, oncologists, and internists should be aware of this secondary effect of vaccination to obviate unnecessary changes in management, unnecessary patient emotional stress, or biopsy."

Clear guidelines

Finally, in a special report -- also published February 24 in Radiology -- Anton Becker, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City and colleagues offered the following guidelines for considering COVID-19 vaccine effects on imaging.

- COVID-19 vaccination shouldn't be delayed because of scheduled imaging for patients with cancer or those being screened for cancer. Perform imaging before vaccination if possible.

- If imaging is done after vaccination, postpone for at least six weeks after final dose. Administer vaccination on the opposite side of the (suspected) cancer and administer both doses on the same side.

- Vaccination information (dates, injection sites, type of vaccine) should be included in a pre-imaging questionnaire.

- In patients with post-vaccination adenopathy, consider observing for six weeks until resolution before proceeding with additional imaging.

"Clear and effective communication between patients, radiologists, referring physician teams and the general public should be considered of the highest priority when managing adenopathy in the setting of COVID-19 vaccination," Becker and colleagues concluded.