The dread of breast cancer far exceeds its actual incidence, especially in young women, as radiologists know. Yet certain women are at risk for developing breast cancer in their thirties or even younger.

Mammography has several disadvantages for screening such women, primarily due to the high density of tissue in the young breast. Therefore, radiologists need to be flexible regarding the imaging modality chosen, and must collaborate well with referring physicians to make sure that a proper history has been obtained on such patients.

In several interviews, experts on breast imaging and breast cancer discussed with AuntMinnie.com the incidence of and risk factors for early breast cancer, appropriate screening schedules for at-risk women, and the appropriate imaging modalities when screening young women.

Primary relative with premenopausal diagnosis

In women who are 30 and younger, the lifetime risk of getting breast cancer is at most one in 5,000, according to breast imaging expert Dr. Michael Linver. In contrast, women who are 50 years old have a one-in-50 lifetime risk, Linver said.

Linver is a clinical associate professor of radiology at the University of New Mexico and the director of mammography at X-Ray Associates of New Mexico, both in Albuquerque. Linver also organizes the "Mammography in the next Millennium: Screening and Beyond" conference, a four-day event devoted to evaluating 100 screening mammograms on the viewbox.

For women in their twenties, the general risk is infinitesimal, according to Dr. Daniel Kopans, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School and the director of breast imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston.

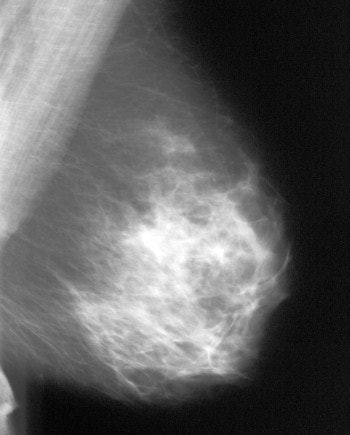

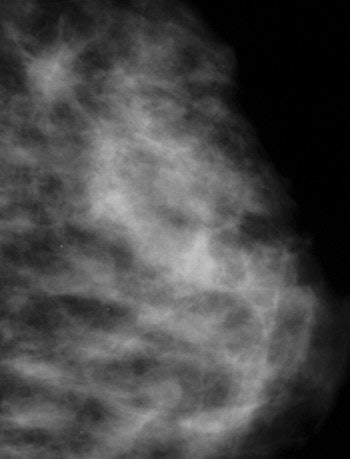

|

| An example of a less-dense glandular pattern more often seen as women reach middle age. Breast cancer is easier to detect against a background of more fatty tissue. Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Linver. |

"Breast cancer is, fortunately, extremely rare among women 35 years old and younger," he said. "For women age 20 there are approximately one to two cases of breast cancer each year for every 100,000. For women age 25, there are approximately eight cases per 100,000."

"By the age of 85, the lifetime risk is one out of 8," Linver added. He encouraged radiologists to discuss these statistical nuances to counter the simplistic message in mainstream media that one of every eight women gets breast cancer.

"Among women who get early breast cancer, such women are more likely to have mothers or primary relatives who had breast cancer before menopause," Linver explained. "They tend to get breast cancer 10 years earlier than their mothers were diagnosed. In addition, women who have BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations tend to develop the disease before menopause. Therefore, there is more of a genetic and familial component to early breast cancer."

Although Linver’s practice may be seeing an increasing number of early cases, it is not known whether the incidence of early breast cancer has increased over the last several years, he said.

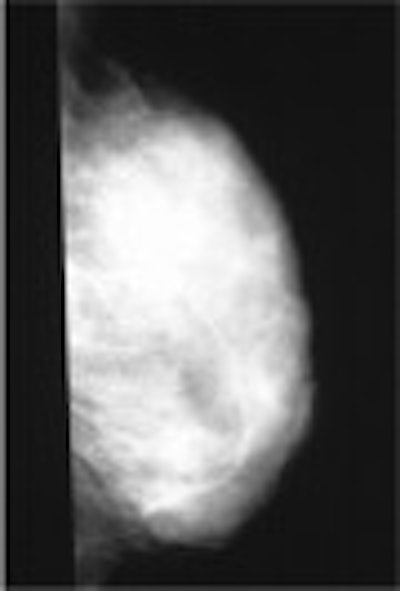

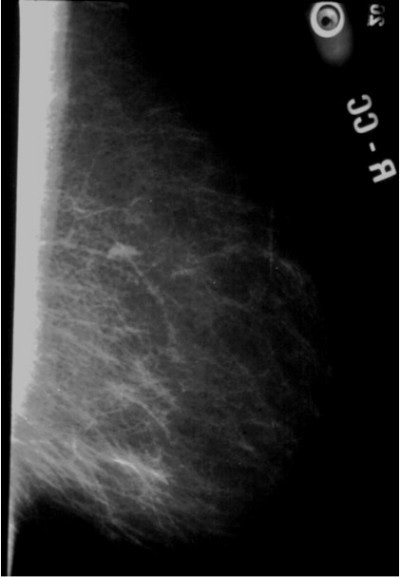

|

| Very dense, glandular pattern seen on mammography in most young women. Breast cancer is extremely hard to find when the breast pattern is this dense, with almost no fatty tissue present. Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Linver. |

Self-breast exams and clinical exams are usually the way suspicious lumps in young women are found, Linver said. "When I ask, ‘Who found this, you or your doctor?’ half of the time the woman found it herself, and half of the time it was the doctor."

Screening younger patients

Breast cancer screening for women with a family history of premenopausal breast cancer should begin when the patient is 10 years younger than the relative was when her cancer was diagnosed, according to Linver.

Kopans suggested that women who have or are at risk of having BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations might want to start screening at approximately 25 years of age. "These recommendations are all ‘best guesses’ since we have no direct evidence that screening these women will save lives," he said.

The challenge in such patients is to use the appropriate imaging modality, according to the experts. Dr. Thomas Kolb, a radiologist in private practice in New York City, was the lead author of a study published last year in Radiology that showed an inverse relationship between breast density and mammography sensitivity, and that dense breast tissue is more common in younger women (October 2002, Vol. 225:1, pp. 165-175).

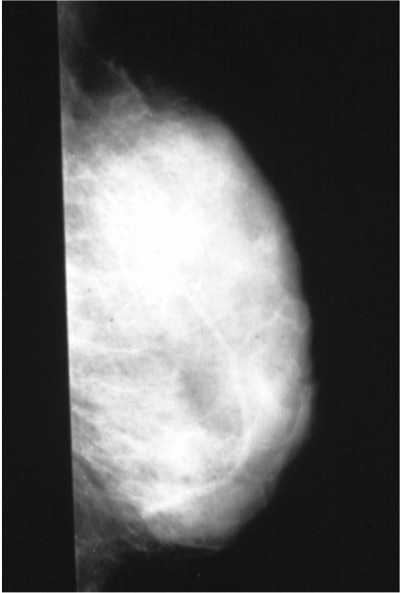

|

| Fatty breast (dark) with 5-mm invasive cancer (white) in upper portion that is easily detectable on mammogram. Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Kolb. |

He said that ultrasound can be a useful screening modality in at-risk young women. "In my practice, I do one or two screening ultrasounds per year in addition to an annual mammogram in high-risk young women," he said. He noted that screening MRI is also being investigated, although he cautioned that neither MRI nor ultrasound are widely accepted breast screening modalities.

"For women younger than 30, there is also some concern that the breast tissues may still be susceptible to radiation carcinogenesis, while the breast tissue of older women is probably fairly ‘radio-resistant,’" Kopans said. "Therefore, it is probably a good idea to limit breast radiation exposures to those cases where it is really medically indicated. Most health planners would argue that the benefit, when weighed against the risks and costs, does not support breast cancer screening before the age of 40."

Linver agreed with this assessment. "Thirty is the cutoff because the breast is more sensitive to radiation before that age," he said. "There is a minimal risk that can’t be ignored in those women, with some very special exceptions." Among women younger than 30 who want to be screened, a strong history must be present in order to justify mammography, he said.

|

| Mammogram of a dense breast, which illustrates the difficulty of detecting a non-deforming, non-calcified small cancer (white) in a background of dense (white) glandular tissue. Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Kolb. |

However, all suspicious lesions should be screened, Kopans cautioned. "If a woman has a lump or suspicious area on her clinical examination, and she is 30 years old or over, a mammogram may be helpful," he said. "Ultrasound is useful to determine if a lump is a benign cyst. Some believe they can differentiate benign lesions from malignant lesions with ultrasound, but I believe this is somewhat risky."

In women younger than 30, a palpable lump is almost always a benign fibroadenoma, and cysts constitute only 3% of such lesions. Therefore, a case could be made that no imaging is needed for lesions in women younger than 30, and that the clinician could make a decision based on the clinical assessment alone, Kopans said.

He urged a cautious approach in the use of MRI and ultrasound as screening modalities. "Detecting breast cancer earlier with x-ray mammography is the only test that has been shown to save lives," Kopans said. "MRI and ultrasound screening may someday help in finding the cancers that mammography misses, but, at this point in time we have no proof that screening with any test other than mammography will save any lives. MRI and ultrasound screening should only be used in properly designed scientific trials and not in general clinical practice."

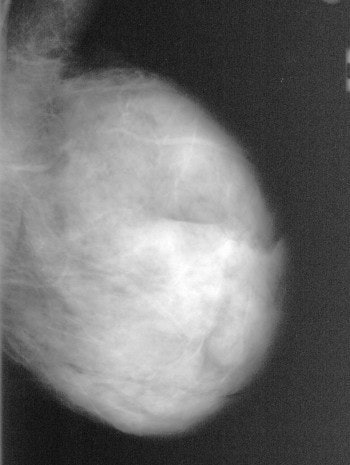

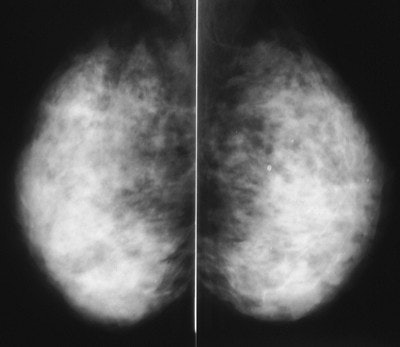

|

| A large cancer is present in the image on the left, but the cancer cannot be seen because it is completely obscured by the dense glandular tissue around it. Note that the breast with the cancer looks exactly like the one without a cancer. The cancer was found here because it was palpable, and was visible on an ultrasound done at the same time as the mammogram. Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Linver. |

Ultrasound should not be ruled out in the young breast, though, said Linver. "If the patient is under 30, ultrasound would be the place to start," he said. "We can find breast cancers sometimes on ultrasound that we can’t find on mammography."

Although ultrasound is more sensitive than mammography, the down side is a risk of false positives, he said. "The big question regarding the cancers caught by ultrasound but missed by mammography is: at what price financially? The answer is, a lot. It costs a lot to do a screening ultrasound and an unnecessary biopsy. There are all kinds of reasons to avoid a screening ultrasound every year. Also, there are no controls over who can do a breast ultrasound, and, as radiologists, we know how important it is to have high-quality imaging."

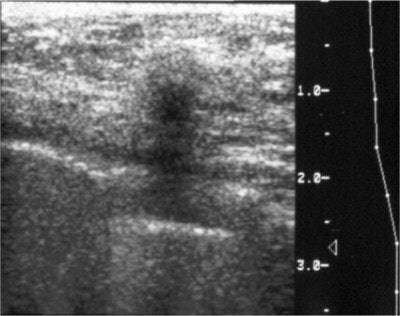

|

| Cancers on ultrasound are usually dark and more easily seen on a background of dense tissue (white). Image courtesy of Dr. Thomas Kolb. |

Linver sees three primary uses for MRI in the breast imaging setting. The most common use is to diagnose a ruptured implant. Second, if breast cancer has been diagnosed, the surgeon will often order an MRI to determine the extent of disease in order to decide whether to perform a lumpectomy or mastectomy. Finally, if a breast cancer patient has a painful lymph node that is found to be malignant, a breast MRI is highly effective for finding the location of the lesion. These indications apply across age groups, he said.

"MRI would almost never be used for screening, but it may be useful in at-risk young women in whom radiation is to be avoided," Linver said. "It finds almost all cancers as well as everything that could be cancer. Like ultrasound, it is highly sensitive, but not as specific as mammography. Also, lesions that are only seen on MRI are hard to biopsy."

With adolescents and young women, less is more

All of the experts interviewed argued against a quick use of imaging with adolescents and women in their twenties, even if they have suspicious family histories. The appropriate imaging modality for adolescents is "none, unless there is an extremely strong family history," said Kolb.

Kopans said, "There is virtually no reason to image the adolescent breast. If any imaging is needed, ultrasound is safe, but since all of the masses in this population are either normal breast tissue, or fibroadenomas, clinical management is usually all that is needed."

|

| This mammogram shows a small cancer in the upper part of the breast, which is visible because the breast tissue is not very dense. Image courtesy of Dr. Michael Linver. |

Linver agreed that if any imaging is appropriate, ultrasound is a good starting point. "If it’s a cyst, you get the answer immediately, and you don’t need follow-up imaging," he said. "If a highly suspicious lesion is found, a focused, coned, tangential mammogram may be appropriate for women in their twenties, but almost never in teenagers. Start with a good physical exam, to be conducted by the woman’s physician. If imaging is appropriate, perform an ultrasound. Then you can decide if anything else is needed. If necessary, a fine-needle aspiration biopsy can be conducted."

Counseling useful for addressing fear

Every time a celebrity’s early diagnosis of breast cancer is publicized, some women become disproportionately fearful that they, too, will get breast cancer. They may show up on self-referral at a breast imaging center and request a mammogram. In such cases, the issue is not the right imaging modality, but a compassionate and knowledgeable physician, said Linver.

"For women who are absolutely paranoid of breast cancer, counseling may be appropriate," he said. In those cases, the patient should be sent back to her gynecologist or primary care provider, he said. Sometimes such women can be reassured by showing them the Gale model, a statistical formula that can calculate an individual woman’s risk relative to the general population. According to this model, Linver said, 75% of women have no breast cancer risk factors.

By Paula MoyerAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

May 2, 2003

References

"Sydney Breast Imaging Accuracy Study: Comparative sensitivity and specificity of mammography and sonography in young women with symptoms," American Journal of Roentgenology, April 2003, Vol. 180:4, pp. 935-940.

"Familial risks, early-onset breast cancer, and BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations," Journal of the National Cancer Institute, March 19, 2003, Vol. 195:6, pp. 448-457.

"Mammography screening matters for young women with breast carcinoma: evidence of downstaging among 42-49-year-old women with a history of previous mammography screening," Cancer, January 15, 2003, Vol. 97:2, pp. 352-358.

"A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer," New England Journal of Medicine, December 19, 2002, Vol. 347:25, pp. 1999-2009.

"High-risk screening: multi-modality surveillance of women at high risk for breast cancer (proven or suspected carriers of a breast cancer susceptibility gene)," Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research, September 2002, Vol. 21:3 supplement, pp.103-106.

"Gray-scale sonography of breast masses in adolescent girls," Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, May 2001, Vol. 20:5, pp. 491-496.

"Spectrum of US findings in pediatric and adolescent patients with palpable breast masses," Radiographics, November-December 2000, Vol. 20:6, pp. 1613-1621.

Related Reading

Non-BRCA mutations may play role in breast cancer risk, March 21, 2003

Gene expression profile predicts breast cancer outcome, December 19, 2002

MRI successfully tracks women with hereditary breast cancer risk, April 8, 2002

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com