The Aztecs of Mexico did it. So did the Mayas of Central America, and various Native American tribes of the Northwest. For these ancient peoples, tongue piercing is thought to have been performed as an offering to the gods, a way to create an altered state of consciousness so that a priest or shaman could communicate directly with higher powers (http://www.holejunkie.com/).

But a 22-year-old woman in New Haven, CT, had her consciousness altered in a less-than-positive way when her tongue piercing gave way to a throbbing headache, nausea, vomiting, and vertigo. While she may have gained some spiritual insight, she also found herself with a cerebellar brain abscess, according to a case report by internal medicine specialists at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven.

The case is one of a number of instances that have been reported in recent years as body piercing has gained popularity, either as a badge of rebellion for teenagers, a talisman of fleeting youth for yuppies, or as a way of life espoused by the modern-primitives movement, which uses body modification to combine high technology with "low" tribalism (CyberAnthropology).

Whatever the justification, a piercing gone awry is not a pretty sight. These days, as easy as it is to obtain a piercing, the potential risks are not so lightly dismissed, wrote Dr. William Dunn and Dr. Teresa Reeves in their case report for General Dentistry.

"The most common complications include pain, edema, and prolonged bleeding immediately after piercing...other serious complications (after tongue piercing) are Neisseria endocarditis, Haemophilus aphrophilus, and Ludwig's angina," they said (General Dentistry, May-June 2004, Vol. 52:3, pp. 244-247).

Dunn is the director of research at Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland Air Force Base, Texas. Reeves is a staff dental officer at RAF Lakenheath in the U.K.

Imaging isn't always required to assess these patients, but it can prove pivotal in instances where the problem has spread beyond the lingua, which was the case for the pierced patient at Yale.

"Cerebellar brain abscesses most often develop secondary to the contiguous spread of infection from an ipsilateral otogenic site," wrote Dr. Richard Martinello and Dr. Elizabeth Cooney in Clinical Infectious Diseases online (January 15, 2003).

|

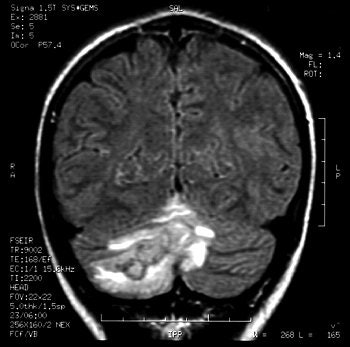

Gadolinium-enhanced MRI scans confirmed the presence of a cerebellar brain abscess in a 22-year-old woman who had undergone tongue piercing four weeks earlier. Images courtesy of Dr Richard Martinello.

|

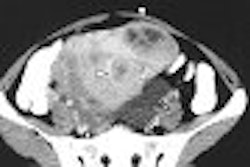

Their patient presented with her symptoms four weeks after her tongue piercing. A neurological exam revealed that the patient was alert, and no abnormalities were found in cranial nerve, motor, or sensory function.

However, a brain CT scan revealed a "right cerebellar enhancing lesion with surrounding edema, and an MRI scan with gadolinium confirmed the presence of a solitary brain abscess," the authors reported. The patient underwent a right suboccipital craniotomy to drain the abscess and was then treated with antibiotics. A follow-up CT showed complete resolution of the abscess.

"A cerebellar abscess occurring secondary to a tongue infection would presumably result from hematogenous spread, because the venous drainage of the tongue flows from the lingual vein into the internal jugular vein," they explained.

|

"As the popularity of body art grows, frequency and spectrum of piercing-site infections may increase. Physicians need to consider piercing sites as a source for potential distant infections," wrote Martinello and Cooney in an abstract for the 2001 Infectious Diseases Society of America conference. Images courtesy of Dr Richard Martinello.

|

In another case, a tongue piercing complication hit closer to home: Periodontologists at the University of North Carolina relied on x-ray to reveal localized loss of attachment thanks to the placement of a tongue stud.

The 22-year-old patient was admitted to the university's department of periodontology in Chapel Hill for the evaluation of the mandibular anterior sextant. Plaque and calculus were visible around the inferior ball of the tongue stud. Dr. Michael Kretchmer and Dr. John Moriarty obtained a periapical radiograph, which indicated horizontal bone loss associated with teeth numbers 24 and 25. The patient removed the stud and was treated with adult prophylaxis and flap curettage. At a six month follow-up, the attachment loss had stabilized.

"The indentations on the lingual surfaces of teeth #24 and #25 directly reflect the shape of the inferior ball of the tongue stud and the configuration of the bone loss present around these teeth," they wrote. "The presence of piercing in the oral cavity should be evaluated with its surrounding structures as a regular parameter when performing an initial exam" (Journal of Periodontology, June 2001, Vol. 72:6, pp. 831-833).

Removing a piercing

In addition, imaging specialists should familiarize themselves with the various types of jewelry used in body piercing, as well as how to safely remove it from a patient, especially if he or she is about to pay a visit to the MR or x-ray suite.

Most tongue-piercing studs are barbell-shaped and made of radiopaque material. As a result, removal will be required, according to Rakesh Khanna and colleagues. They offered a how-to article for removing jewelry in the Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine.

Khanna, who is a specialist registrar in accident and emergency at Staffordshire District Hospital in Staffordshire, U.K., cited the case of a teenage girl who arrived at the hospital in cervical immobilization after a failed suicide attempt by hanging.

"The radiographer requested removal of a lingual bar to visualize the odontoid peg and to facilitate computed tomography," the authors wrote. "(Jewelry) may also require removal to prevent scattering…" (Journal of Accident & Emergency Medicine, November 1999, Vol. 16:6, pp. 418-421).

In the case of an unconscious patient such as this one, Khanna's group recommended that "lingual barbells be removed by exteriorizing the jewelry if possible, and placing a swab beneath the bead as it is unscrewed to prevent possible aspiration."

Because some jewelry is made of ferromagnetic material, it can also be a hazard in the MR magnet. Burns as a result of MRI-related heating are also a risk factor, according to guidelines published by the Institute for Magnetic Resonance Safety, Education, and Research.

Besides barbells, other common jewelry include labret studs (straight bar with a ball threaded on one end and a permanent disc on the other) and a captive bead ring (small, dimpled bead held in place by the tension from an incomplete ring).

In general, Khanna suggested that holding the bar with artery forceps and unscrewing the bead is the best way to remove barbell jewelry. For an embedded labret stud, his group recommended compressing the odematous tissue and pushing the jewelry through to expose the bead and remove it with forceps. Finally, captive rings can be taken out by releasing the tension on the bead.

Should the patient decline to remove the jewelry, there are other options: MRIsafety.com recommends stabilizing it with adhesive tape or a bandage. This should prevent the jewelry from moving or becoming displaced inside the magnet. Another alternative is to direct the patient to purchase a piercing retainer, a plastic barbell that can be used in place of the jewelry before and during imaging.

By Shalmali PalAuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 19, 2004

Related Reading

Nailed in the head: X-ray, CT show patient's good luck, July 13, 2004

CT can reduce unneeded laparotomy for patients with gunshot wounds, May 21, 2004

Radiographs improve treatment of land mine injuries, June 27, 2003

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com