Rudiger Gamm can calculate 53 to the ninth power. In his head. He can also divide 31 by 61, and calculate the answer to 60 decimal points.

The 26-year-old German prodigy’s talent, which wins him easy cash on TV quiz shows, attracted the curiosity of French and Belgian researchers who imaged his brain with PET while he performed math problems.

They found that Gamm harnesses the brain’s long-term memory network in order to solve complex calculations, according to their study published in the latest issue of Nature Neuroscience (January, 2001, Vol. 4:1, pp.103-107.

Most people perform calculations using short-term working memory, a sort of mental note pad that stores only information associated with the task at hand. It can hold about seven unrelated items at once, which is why most folks can only conduct simple calculations such as determining a tip or multiplying five by 31.

But Gamm performs calculations that require remembering 20 or 30 steps simultaneously, which led the researchers to conclude that he somehow stores task-related math information in his long-term memory.

"It’s similar to your computer using its hard drive to expand the capacity of its virtual memory," said Dr. Brian Butterworth, a professor of cognitive neuropsychology at University College London who has written extensively on how the brain is hard-wired for math.

In addition, Gamm taps into a special kind of long-term memory called episodic memory, noted the study’s lead author, Dr. Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, a radiologist with France's National Center for Scientific Research. This especially powerful form of memory is so-named because it archives the episodes of one’s life, such as the color of a childhood bicycle or a first visit to the ocean.

|

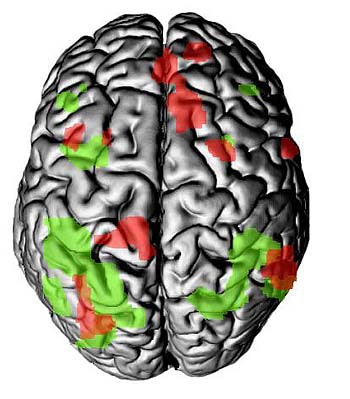

PET image of the brain showing areas that are active in both six non-expert calculators and Gamm (green), and areas that are active only in Gamm (red). Image courtesy of Dr. Tzourio-Mazoyer; originally published in Nature Neuroscience.

Tzourio-Mazoyer’s study isn’t the first time scientists have examined a gifted brain. Researchers analyzed Lenin’s brain a few years after his death and found that he possessed a large number of specialized neurons that enable different regions of the brain to communicate with one another.

Einstein’s brain -- which after his 1955 death spent several decades floating in a mason jar in a Kansas pathology office -- has passed from neurologist to neurologist in recent years. A study published in Experimental Neurology determined that the pioneering physicist boasted an unusually high number of information-transfer cells in areas of the brain that control memory, language, and abstract association (Experimental Neurology, 1985, Vol. 88, pp. 198-204).

And a 1999 Canadian study published in Lancet determined that the portion of Einstein's brain that governs mathematical and spatial reasoning was especially large (Lancet, June 19, 1999, vol. 353, pp. 2149-2153).

The brain at work

But no one had witnessed a gifted brain at work until this study. Using PET, the researchers measured Gamm’s cerebral blood flow while he performed math problems. They also imaged six people who possessed normal math skills while they performed the same calculations. In each study, a single 90-second scan was acquired and reconstructed into a 3-D image.

Both Gamm and the control group showed activation in the left side of the brain, particularly in areas associated with visual and spatial interpretation. This alone is a new finding, said Dr. Mauro Presenti, a co-author of the study and a neuropsychologist with Belgium’s National Fund for Scientific Research.

"We didn’t know whether people used the brain’s verbal or visual areas during calculations," Presenti said. "We now know that expert and non-expert calculators use essentially visual strategies."

But only Gamm exhibited increased blood flow in a network of areas associated with long-term memory, including the right medial frontal cortex and the parahippocamal gyri. This suggests that cognitive expertise is not simply a matter of faster thinking, Presenti said, but rather it involves using new processes and incorporating areas of the brain not used in normal people.

Ironically, Gamm didn’t show an aptitude for math until the age of 20, when he became interested in entering a TV competition in which contestants win bets by solving calculations. He trained fours hours a day, learning various math algorithms and calculation laws. Presenti said he believes this intensive day-after-day training regimen triggered the same area of the brain as other long-term, episodic memory processes.

"Through practice, Gamm developed procedures for efficiently encoding and retrieving specific information in long-term memory," Presenti explained.

While Gamm’s talent is not commonplace, it isn’t rare either. In a commentary that accompanied the study, Butterworth noted that some musicians can play tunes after only hearing them once, and expert waiters can remember the orders of 20 people.

"The study shows that anyone can develop exceptional capacities if they work at it," Butterworth said. "It also shows how developing an expertise enables one to recruit new brain areas to carry out tasks in the domain of expertise."

In Gamm’s case, he circumvented the limited capacity of short-term memory by momentarily saving the intermediate steps of a complex math calculation in his long-term memory -- a tremendously efficient process compared to how most people mentally juggle numbers.

"When somebody gives you a phone number, it’s not difficult to remember it for a few minutes before dialing it," Tzourio-Mazoyer explained. "But if you receive more information, the phone number is pushed out and you forget it. Likewise, try to solve 75 x 49, and you will find that it’s difficult to keep ‘online’ the different intermediary results."

By Dan KrotzAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

February 21, 2001

Click here to post your comments about this story. Please include the headline of the article in your message.

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com