Former basketball all-star Bill Walton calls himself "the most injured athlete in history." He was certainly among the most talented. In the 1970s, Walton made the leap from three straight College Player of the Year awards with the powerhouse University of California, Los Angeles' Bruins to star center for the Portland Trail Blazers.

By 1978, Walton was the league's MVP and the Blazers were the reigning world champions; together they were leading the National Basketball Association (NBA) 50-10 when Walton's metatarsal split in half. The reason: an undiagnosed stress fracture. It was the first in a series of foot and ankle injuries that would cause him to miss nine and a half seasons, and would eventually sink his career.

Unfortunately, many other hoop stars suffered a similar fate. In the 1980s, multiple stress fractures resulting from an undiagnosed bilateral tarsal coalition ended the career of Philadelphia 76er guard Andrew Toney, whom veteran coach Pat Riley called "the greatest clutch player I've ever seen." Fast-forward to 2002, when foot stress fractures benched Sacramento Kings' starting point guard Mike Bibby, and Utah Jazz center Curtis Borchardt missed his entire rookie season thanks to the uncooperative pin holding his foot together.

Obscure anatomy

According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, a stress fracture "is an overuse injury that occurs when muscles become fatigued and are unable to absorb added shock. Eventually, the fatigued muscle transfers the overload of stress to the bone, causing a tiny crack."

An estimated 16% of all athletic injuries are stress fractures, and metatarsal stress fractures comprise 25% of those. Among basketball players, they occur most often in the fifth metatarsal, behind the little toe.

Little formal data exists concerning the frequency of metatarsal stress fractures. Most studies come from the military, where such injuries are called march fractures.

"Plain film radiographs are frequently unrevealing. Confirmation ... is best made using triple-phase nuclear medicine bone scan or MRI," wrote Dr. Brent Sanderlin and Dr. Robert Raspa from the Naval Branch Medical Clinic in Fort Worth, TX, and the Naval Hospital Jacksonville in Florida, respectively (American Family Physician, October 15, 2003, Vol. 68:8, pp. 1527-1532).

In fact, the limitations of imaging during Walton's era may have been part of his problem. He partially blames the duration and severity of his injuries on doctors who didn't believe he was hurt -- as doctors might well have thought back then.

As of the mid-1970s, SPECT and MRI were still in their infancies and not widely available, and CT scans were blotchy by modern standards. Little wonder, then, that Walton's doctors missed the big picture.

Though imaging technologies improved by 1991, an article published that year in the Journal of Foot Surgery (the year after Walton's first ankle fusion) compared x-ray, CT, bone scintigraphy, and MRI exams of stress fractures. The authors from the University of California, San Diego concluded that ultimately, the most effective tool for detection is "a keen sense of suspicion" (January-February 1991, Vol. 30:1, pp. 85-97).

Luckily for today's athletes, medical imaging advanced enormously in the following decade. Dr. Andrew Cosgarea, director of Johns Hopkins University's sports medicine division in Baltimore and the school's head team physician, is also the orthopedic surgeon for the Baltimore Orioles.

"We use MRI, bone scan, x-ray and, most importantly, we use clinical history and physical examination," he said. "We use MRI for stress fractures in a lot of different areas. It's becoming more and more accepted as a good way of assessing them."

Missing an injury "could make the situation worse," Cosgarea warned. "An impending stress fracture in the foot could require surgery. A hip stress fracture, in a worst-case scenario, could lead to hip replacement."

NBA action

After losing Walton and too many other stars to stress fractures, the NBA finally decided to do something. The upshot was a 1994 study, funded by the NBA and the Dr. Scholl's company, on the connection between stress fractures and high-impact landings.

"That project focused on a wide variety of kinematic and force variables during simulated basketball movements," said Philip Martin, Ph.D., professor and head of the department of kinesiology at Pennsylvania State University in University Park, who participated in the study. "It was motivated by a concern about the high incidence of stress fractures in NBA players. Data were collected on 24 players from five different NBA teams."

The study showed that the most severe stresses occurred from layup landings, which produce peak vertical forces averaging 8.9 times body weight, and as much as 14.58 times body weight. Translated in terms of a 6' 11", 235-lb player like Walton, that's an average force of 2,090 lb -- and possibly more than 3,400 lb -- on the player's feet (Journal of Applied Biomechanics, 1994, Vol. 10, pp. 222-236).

A pair of newer studies went even further, identifying not only the specific types of basketball movements most likely to cause foot stress fractures, but also mechanisms that could prevent injury, such as arch supports and orthotics. Both studies were conducted in 2004 at Duke University's Sports Medicine Center K-Lab in Durham, NC.

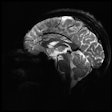

|

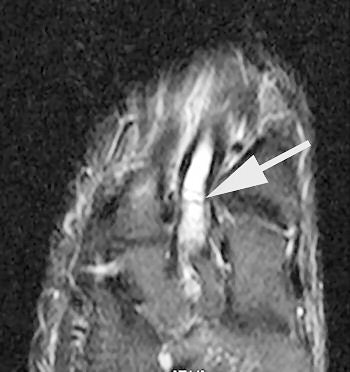

| MRI shows bone marrow edema at the base of the fifth metatarsal. All images courtesy of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. |

The first study was led by Dr. Joseph Guettler, now an orthopedic surgeon at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, MI. It revealed that the greatest load on the fifth metatarsal occurred from pivot moves during a forward sprint, and it challenged the long-held but scientifically unfounded notion that high arches contribute to foot injuries.

|

| Short axis image shows bone marrow edema at the base of the third metatarsal. |

Counter to shoe manufacturers' assumptions, the study showed that arch support seems to shift stresses away from the fifth metatarsal ("Fifth Metatarsal Stress Fractures in Elite Basketball Players: Evaluation of Forces Acting on the Fifth Metatarsal," American Academy of Orthopedic Surgery meeting, March 13, 2004).

The follow-up study was led by Dr. Nancy Major, associate professor of radiology at Duke University Medical Center's musculoskeletal division. Her study determined that MRI can effectively predict metatarsal stress fractures by depicting bone marrow edema (a precursor to fractures), thereby enabling the prevention of potential fractures with the use of orthotics.

In this study, 26 male basketball players from Duke and North Carolina Central University in Durham were imaged before and after their 2003 season. Although 19 of 52 feet showed abnormalities with MRI, only one player had complaints of a symptomatic midfoot. The use of an orthotic provided immediate relief, and the player did not subsequently develop stress fractures.

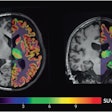

|

| Short axis image shows bone marrow edema at the base of the third metatarsal. |

A player experiencing no symptoms, however, did develop a metatarsal stress fracture before he could be fitted for an orthotic ("The role of imaging in the feet in asymptomatic collegiate basketball players," RSNA meeting, December 2, 2004).

Major's study was funded by Nike, which was looking for help in redesigning its shoes.

"The big benefit for Joe Average and the kids who aren't at the elite level is a better shoe design to prevent this kind of injury," Major said. "It can also apply to the military, where soldiers run long distances."

As for elite athletes, they'd score more than better shoes if MRI scanning for bone marrow edema were adopted as a screening method. At the collegiate level, Major said, "you would want to know what the health of their feet is going to be. You can change what's going to happen for a player, especially if he has aspirations to play professionally. Going into the draft or being scouted, he doesn't want to be benched."

|

| Delayed image shows increased bone marrow edema and fracture line, base of second metatarsal. |

Cosgarea agreed. "The real question every physician's got to ask themselves is not so much what's the consequence of the injury, but what's the consequence of missing the injury?" he said.

The short answer is emergency surgery, parts replacement, and delay of return (or not) to sports. Just ask Bill Walton.

By Sydney Schuster

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

December 9, 2004

Related Reading

Rowers facing more rib stress factures, August 23, 2004

Accidents and patellar overuse plague competitive cyclists, August 16, 2004

Just (over) Do It! Imaging pegs overuse injuries in specialty sports, October 8, 2003

MR categorizes acute hamstring injuries for pre-op assessment, September 29, 2003

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com