CHICAGO - Image-guided percutaneous cryoablation of cancer metastases is safe and effective in reducing pain in patients who have not received relief from other treatments, according to the findings from an ongoing study presented at the 2006 RSNA meeting.

"Our preliminary results suggest that cryoablation provides an alternative treatment for patients with painful metastatic disease," said Dr. Matthew Callstrom, Ph.D., in a presentation on Sunday. "It is important to note that these are patients who have failed conventional therapies."

Callstrom, an assistant professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, MN, and colleagues are conducting an ongoing clinical evaluation using image-guided percutaneous cryotherapy for treatment of painful metastatic tumors involving bone. The researchers will eventually enroll a total of 30 patients with various metastases caused by different cancers, but Callstrom reported on the findings from 28 of those patients who have two to 24 weeks of follow-up.

The group is studying the ability of cryoablation to relieve pain rather than other methods such as radiofrequency ablation, Callstrom said. While radiofrequency ablation is successful, it can take as long as six weeks for pain to be reduced to normal, and in 70% of cases, pain can actually increase immediately after treatment, he noted.

For their study, the researchers treated patients with metastases involving the clavicle, vertebral lamina, chest wall, iliac bone, sacrum, and ribs. Primary lesions included colorectal, renal cell, bronchogenic, squamous cell, adrenal cortical, ovarian, and thyroid carcinomas, as well as paraganglioma, melanoma, and desmoid tumors, according to the researchers' RSNA abstract.

Upon entry into the study, the patients reported moderate to severe pain, scores ranging from 4 to 10 out of 10 using the validated Brief Pain Inventory, in the previous 24-hour period, with an average pain score of 7.5, a severe pain indication. The patients continued to have pain despite previous surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or combinations of the treatment. About 21% of the patients, however, had neither chemotherapy nor radiation upon entry into the study. Patients with spinal cord metastases were excluded.

Within four weeks of treatment, 30% of the patients were pain-free and 68% of patients were able to report a three-point drop in pain scores, Callstrom said. "A reduction of two points is considered clinically meaningful," he noted.

The reduction in pain reached statistical significance as well at the p <0.0001 levels, Callstrom said. The pain reduction was also significant at eight weeks, dropping about another point, and was sustained at least as long as 24 weeks.

The researchers also evaluated quality of life status, looking at how much pain interfered with the person's activities of daily living. The improvement in quality of life reached statistical significance at four weeks (p = 0.0005) and eight weeks (p = 0.0007), Callstrom said. The interference scores were 5 prior to the minimally invasive cryoablation procedure, and they dropped to between 1 and 2 points after the treatment.

In the follow-up period, no major or minor complications have been reported, he said.

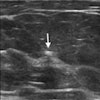

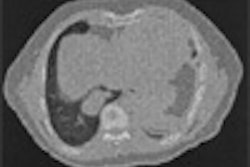

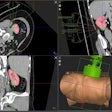

"The ice ball that is generated by the cryosurgery covered the entire metastasis and can be seen very easily with CT monitoring," Callstrom said in his discussion. "The treatment is safe. The pain relief is dramatic and durable."

The trial, supported by Endocare of Irvine, CA, is being expanded into a multicenter study, he said.

"Painful metastases are a serious, difficult problem that is a strain on the patient, the hospital, and the system," said session moderator Dr. Kevin Dickey, an interventional radiologist at New Britain General Hospital in New Britain, CT.

"This cryoablation procedure can be done as an outpatient procedure, and we can actually see how the ice ball engulfs the tumor," he said. "This treatment is a plus in treating patients without having to load them up with narcotics."

By Edward Susman

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

November 27, 2006

Related Reading

Percutaneous cryoablation helpful against renal tumors, March 8, 2006

MR-guided cryoablation promising against renal tumors, August 5, 2005

Cryoablation provides effect palliation for bone metastasis, April 4, 2005

Percutaneous cryoablation reduces pain in patients with advanced cancer, March 8, 2005

Single-fraction radiotherapy effectively treats painful bone metastases, October 10, 2003

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com