Amid concerns as to which physicians should be reading magnetic resonance images, a new study has found almost 10% of cardiac MR scans include important noncardiac findings.

Dr. Kai-Uwe Waltering, a radiologist in training at the University Hospital in Essen, Germany, presented his group's latest data on Saturday at the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR) meeting in San Francisco.

The Essen researchers collected data on some 2,099 patients who underwent cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) during the 30-month period between April 2002 and September 2004.

Of those patients, 985 were referred to CMR for detection of ischemia, 756 for assessment of myocardial viability, 197 for assessment of masses or thrombi, and 161 for myocarditis or cardiomyopathy.

All of the examinations were read by a cardiologist and a radiologist, who arrived at a consensus interpretation.

Along with many irrelevant findings and some reconfirmations of established conditions, the scans of 206 patients revealed 222 clinically relevant noncardiac findings that were unknown prior to the CMR.

Of the 206 patients, 101 were immediately referred for additional diagnostic CT or MRI, which confirmed the diagnosis in 85% of those patients. Another 67 were referred for follow-up examinations at six months, and 38 patients were lost to follow-up.

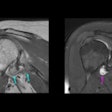

Of the 222 clinically relevant noncardiac findings, 86 were thoracic pathologies, including 30 pulmonary lesions, nine hilar masses, 13 hilar lymph nodes, eight mediastinal masses, and 26 mediastinal lymph nodes.

Seventy-six of the findings were vascular variants or pathologies, including 66 dilations or aneurysms of the thoracic aorta, one right descending aorta, four aberrant subclavian arteries, three pulmonary emboli, one persistent left superior vena cava, and one vena cava thrombus.

Abdominal findings comprised 28 of the findings, including 25 noncystic liver lesions, one renal cell carcinoma, one hydronephrosis, and one spinal metastasis.

The percentage of patients found to have relevant noncardiac findings was slightly higher at 30 months into the study than at an earlier point reflected in the group's SCMR meeting abstract (Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, January 2005, Vol.7:1, pp. 68-69).

As of December 2003, the researchers had documented a total of 1359 cardiac MR referrals. Among those patients, 118 (8.7%) had relevant, previously unknown noncardiac findings.

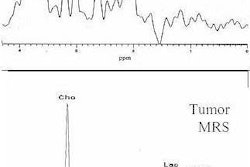

The exams were performed on a 1.5-tesla Sonata system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany), using axial HASTE (TR 2RR, TE 23 ms, FA 160°), as well as cine SSFP and IR-FLASH sequences.

In an interview with AuntMinnie.com, Waltering said his group performed their research to quantify their anecdotal experience with HASTE MR sequences covering the entire chest.

"We found that there are relevant noncardiac findings very often, and we found that many of those findings were unknown prior to our CMR study," Waltering said.

But while their anecdotal experience is undoubtedly familiar to other practitioners, Waltering said the medical literature offers little data on the prevalence of noncardiac findings on cardiac scans. He cited one earlier study led by an Essen colleague that looked at noncardiac findings on electron beam CT scans of the heart.

Earlier this year, radiologists from Johns Hopkins in Baltimore also presented data on noncardiac findings in CT angiography scans at the American College of Cardiology meeting in New Orleans last November.

Unlike the situation at many facilities in the U.S. and Europe, Waltering said relations between the cardiologists and radiologists at the University Hospital in Essen were quite harmonious, allowing collaboration that benefits patient care.

In his opinion, Waltering said, "it's very important that radiologists look at the cardiac MR studies" because they know the MR appearance of the noncardiac findings much better than the cardiologists.

In their abstract, the Essen researchers' official conclusion is that physicians who read CMR studies must focus on all visualized organs, and "should be trained in cross-sectional anatomy and the MR appearance of noncardiac diseases."

That's a view shared by the SCMR, which several years ago established its own guidelines as to the training required for interpreting cardiac MR scans (Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, October 2000, Vol. 2:3, pp. 233-234).

"People who are trained in CMR can also be trained for these (noncardiac) issues as well," said Dr. Warren Manning, the current SCMR president, in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

"At the same time, there are many people who are performing CMR today who are doing it, as at our site, in joint collaboration between cardiology and radiology," said Manning, who is also section chief of noninvasive cardiac imaging at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

"That's another model, but it's not a model that (the SCMR) believes must exist," Manning said. "It's certainly just one of many options."

By Tracie L. Thompson

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

January 28, 2005

Related Reading

Medicare panel endorses national privileging, Stark changes, January 18, 2005

ACR to pitch Congress on 'designated physician imagers' for Medicare, January 6, 2005

Nation's largest insurer to adopt ACR criteria, accreditation, December 9, 2004

High noncardiac yield mandates rad involvement in CTA, November 11, 2004

Radiologists (mostly) cheer as insurers set imaging rules, November 4, 2004

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com