By Dr. G. Eric Morgan

If you asked a resident to choose one of the following as the definition of mammography, which one would get the most votes?

A) Radiographic examination of the breasts.

B) X-ray examination of the breasts (as for early detection of breast cancer).

C) A word that evokes maximal fear in unsuspecting radiology residents. Sometimes said with vehemence and egregious hissing to denote disdain.

Research has shown that residents today make a concerted effort to avoid a career in breast imaging. There are many reasons for their abhorrence: lack of interest, fear of lawsuits, inherent stress.

Why does the very idea of breast imaging twist motivated, inspired residents into scowling malcontents? And what would it take to entice radiology residents back to breast imaging? Or is it too late?

Anatomy

The first thing any med student learns is anatomy, and the subject is an ongoing focus throughout radiology residency. Once the imaging appearance of normal structures is mastered, we have a platform on which to grow. Many programs focus initially on being able to distinguish normal from abnormal (which sounds easy enough, until you try it).

By the first year of residency, we know that anterior to the pancreas and posterior to the stomach is the lesser sac. We know to look just inferior to the terminal ileum on a CT scan to find the origin of the appendix and rule out appendicitis.

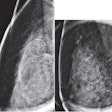

Unfortunately, all that anatomic certainty goes out the window with breasts. Between the nipple and chest wall, there’s a lot of...black. The breast presents a conundrum. For example, the attending points into the starry sky of fatty breast tissue and confidently asks, "Can’t you see the architectural distortion?"

To which we vacuously reply, "No, but there’s Sagittarius." ‘Recycle’ is promptly stamped on our evaluation.

And even the staff seems less than certain sometimes, which only makes it worse for us: When one person unequivocally calls tenting of the posterior parenchyma on the CC view and another blithely dismisses it, we are confused.

Then there are dense breasts -- we get as much information from a dense-breast mammogram as from looking at a bag of cotton balls. There are a lot of extremely dense breasts out there, leading to such reports as: "There are numerous curvilinear, partially border-forming dense opacities. Cannot exclude pathology of any sort."

Reading films

Basically, we’re looking for something to clear up all that confusion -- to make breast imaging better and easier. Many advocate ultrasound for screening because of claims of clearer anatomy and improved detection. Proponents of MRI advocate its use in subsets of high-risk women, citing cross-sectional techniques and contrast enhancement characteristics for easier imaging and improved diagnostic sensitivity.

If definitive studies show that these modalities improve early cancer detection, we are going to need more radiologists to perform the exams as well as interpret them. Perhaps this is the carrot that needs to be dangled before residents -- optimization of breast imaging is the key.

Let’s face it, most of us don’t care about the paperwork and other bureaucracy associated with imaging. We care about the patients and reading the films. While the basics must be mastered early -- techniques, patterns of normal and abnormal breast tissue, ACR classifications, appropriate recommendations -- maybe the focus should be on training residents to go beyond cranking out a read on nebulous mammograms, and doing what generates revenue: diagnostic exams, ancillary imaging (US, MR), and biopsies.

Contending with Big Brother

I can almost feel the draconian hand of the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) push me into the chair each time I saddle up to the lightbox. The government makes quality control in breast imaging cost a fortune, but reimburses a modicum for each screening exam. Financial viability is a joke, unless you operate a massive, well-oiled mammography center.

While the intention of improved patient care is honorable, the bureaucracy makes things difficult. Now lawmakers are toying with the possibility of mandatory testing for radiologists who perform breast imaging, but with no foreseeable change in reimbursement rates.

From a purely financial standpoint, what would it take to stop residents from running away from mammo?

The obvious answer would be to make it profitable; to fully reimburse screening mammograms at their value; and to support and reduce potential malpractice exposure. But since when did logic factor in when there is cost-cutting to consider?

Reading screening mammograms in a rapid, undisturbed, accurate fashion lets us do what we love -- imaging. Magnification views for the calcifications? Ultrasound for masses? Cross-sectional imaging? Bring it on. And for those of us who enjoy procedures and face-time with patients, biopsies are awesome. Guess what? This is where the money is, too. Suddenly, mammo doesn’t sound so bad.

If you want to help residents appreciate mammo, teach them how to make the system work for them. Help them to screen a mammogram in seconds, not minutes. Teach them the subtleties of breast ultrasound and MRI. Give them the experience in stereotactic and ultrasound-guided biopsy. Give them the experience to make it interesting and the tools to make it profitable.

Litigation

I know that I am not the only one who is afraid of getting sued. A recent study suggested that the fear of being slapped with a malpractice suit is one of the reasons that North American mammographers make more false-positive calls.

Most litigation results from communication breakdown -- the patient feels left out, deceived, betrayed. The majority of patients know we are human; they just want us to act like one. That may mean telling them what we are thinking, being honest, and offering encouragement and support. When we make a mistake, ‘fess up and try to make it right.

Granted, there are lawyers out there who will come after us anyway, but at least we did the right thing.

Each time we read a mammogram, we enter the most litigious arena of radiology. Why should we read them at all? What can today’s mammographers and educators do to pique our interest?

- Encourage competency in diagnostic breast imaging. Also, don’t limit resident education just to what it takes to pass the boards: help them understand how to optimize breast imaging with advanced technologies.

- Facilitate patient education and interaction to reduce patient duress and the potential for litigation.

- Impress on residents how doing their part with mammography makes them more marketable to a private-practice group. Offer examples and business models of practices that have made breast imaging profitable -- an organized practice can be profitable.

I once remarked to a friend of mine in private practice how much mammo reading turned my stomach. He told me that we have to be able to do it all, not just for our practice, but also for our patients. The more I think about that, the more I agree.

By Dr. G. Eric MorganAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

October 16, 2003

Dr. Morgan is a radiology resident at the Madigan Army Medical Center in Tacoma, WA.

The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the author and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Defense; nor do those opinions necessarily reflect the views of AuntMinnie.com.

Related Reading

Malpractice fears may initiate more false-positive mammograms in North America, September 16, 2003

Making mammographers better: The last link in the imaging chain, August 29, 2003

Radiology residents not interested in reading mammograms, June 9, 2003

Driving improvement without driving the docs away: rethinking the MQSA, May 27, 2003

Radiologists say training, not tests, will hone mammography skills, April 10, 2003

Copyright © 2003 AuntMinnie.com