A new study further confirms that youth football players who experience repeated exposure to head impacts -- both in games and practices -- have a higher number of abnormal voxels in brain MRI scans. The research was published June 15 in the Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics.

The results highlight the need for more study on the long-term impact of contact sports on young people, wrote a team led by Mireille Kelley, PhD, of Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, NC.

"[Future] investigations into the long-term relationship between head impact exposure and neuroimaging findings are warranted to better understand how reduction in subconcussive head impact exposure may affect the brain over many years of participation in football," the group noted.

Previous studies have examined the effect of head impacts on youth athletes, noting a general trend toward increasing exposure among youth through college age, the team wrote. Some estimates say that high school football players can sustain up to 1,200 impacts in a season, with exposure influenced by season length and player position. And these impacts can have long-term effects.

"A growing body of evidence has demonstrated that accumulation of repetitive concussive and subconcussive head impacts throughout many years of participation in contact sports may contribute to later-life neurodegenerative diseases," Kelley and colleagues wrote.

But how repetitive head impacts actually affect a young person's brain over the long term has been somewhat unclear. So Kelley's group used MRI to investigate changes in head impact exposure among youth football players over a number of seasons to assess whether any changes in this exposure matched changes in imaging metrics.

The study included 47 young people who participated in youth football for two or more consecutive years between 2012 and 2017. All of the players wore helmets with the Riddell Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) -- which measures linear and rotational head accelerations that occur during a head impact -- during both practices and games; study data covered 109 football seasons and 41,148 head impacts. None of the 47 participants were diagnosed with a concussion during the research time frame.

On the impact side, investigators tracked the following:

- Number of head impacts

- 50th percentile of impacts per football session (games and practices)

- 95th percentile peak linear and rotational accelerations measured by the Head Impact Telemetry System

- Risk-weighted cumulative exposure (i.e., the frequency and magnitude of head impacts experienced by an athlete over a season)

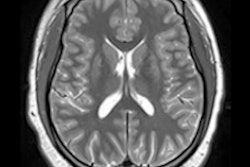

On the imaging side, the researchers compared abnormal white-matter areas between two groups: 19 of the 47 youth athletes who had pre- and postseason diffusion-tensor MRI (DTI-MRI) brain images for two consecutive football seasons available, and a control group of 16 youth athletes who participated in noncontact sports and who also underwent DTI-MRI twice, once at baseline and another four months later.

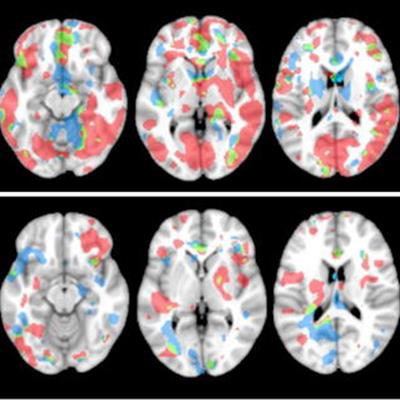

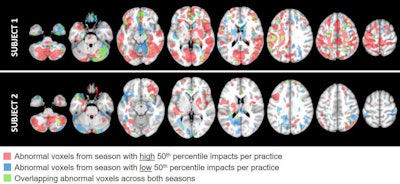

Brain MRI scans of two football players who experienced a different number of head impacts during their seasons. Subject 1 experienced more head impacts during the season, as indicated by more abnormal voxels on diffusion-tensor MRI scans of white matter compared with subject 2. Image and caption courtesy of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS).

Brain MRI scans of two football players who experienced a different number of head impacts during their seasons. Subject 1 experienced more head impacts during the season, as indicated by more abnormal voxels on diffusion-tensor MRI scans of white matter compared with subject 2. Image and caption courtesy of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS).Kelley's group found that head impact exposure varied year-to-year and between athletes, as did increases or decreases in the number of abnormal white-matter areas in the players' brains. But there was a definite link between changes in head impact exposure and presence of white-matter abnormalities, particularly in the DTI measure of mean diffusivity, which showed a 63.3% increase of abnormal voxels on brain MRI in second season compared with first season. The researchers also found that incidence of head impacts sustained during gameplay increased by 54% over the course of three seasons, from 86 to 133.

"There were several significant positive correlations between changes in the total number of impacts and impacts per session, especially during practices, and changes in neuroimaging metrics," the team wrote. "These results suggest that, among individual athletes, increases in head impact exposure from one season to the next were associated with a greater number of abnormal voxels and that decreases in head impact exposure were associated with fewer numbers of abnormal voxels from one season to the next."

Are there obstacles to reducing youth athlete exposure to head impact? Yes -- primarily a lack of consistency across leagues regarding protective protocols, corresponding author Dr. Jillian Urban told AuntMinnie.com via email.

"One challenge in reducing head impact exposure in athletes at the youth level is the large number of leagues in communities with varying levels of regulation," Urban said. "As we improve our understanding of head impact exposure and the context in which head impacts occur in this population, we can work together with members of the youth football community to develop practical and evidence-based strategies to reduce exposure and work to improve the dissemination of these strategies to local youth football leagues."