Researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine have developed a PET imaging technique using a carbon-11-based radiotracer that confirmed an association between post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS) and widespread inflammation in the brain.

The findings could lead to more effective treatment plans for people who experience long-term fatigue, pain, sleep disruption, and "brain fog" associated with PTLDS.

Johns Hopkins researchers have worked for more than a decade to optimize the combination of PET imaging with the radiotracer carbon-11 (C-11) DPA-713, which binds to a translocator protein (TSPO) in the brain. TSPO is released primarily by two types of brain immune cells -- microglia and astrocytes. When brain inflammation is present, levels of TSPO also increase.

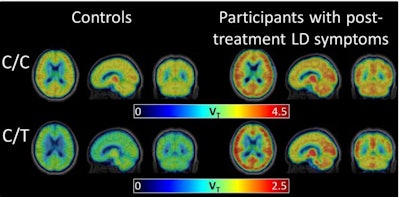

With the combination of PET and C-11 DPA-713, clinicians are hoping to visualize increased levels of TSPO and inflammation and determine where they are occurring in the brain. In the current study, the researchers compared PET scans of 12 patients who were diagnosed with PTLDS with PET images from 19 control subjects without the condition (Journal of Neuroinflammation, December 19, 2018).

Across eight different brain regions, the PET scans revealed significantly higher levels of TSPO in the PTLDS patients than in the controls. When the researchers adjusted for genotype, brain region, age, and body mass index, there was a mean difference of 0.58 in TSPO level between the two groups.

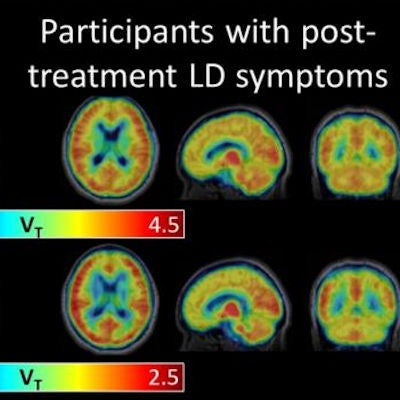

The radiotracer C-11 DPA-713 binds to a marker of inflammation. PET brain scans show elevated levels of the marker in participants with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. Image courtesy of Coughlin et al, Journal of Neuroinflammation.

The radiotracer C-11 DPA-713 binds to a marker of inflammation. PET brain scans show elevated levels of the marker in participants with post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. Image courtesy of Coughlin et al, Journal of Neuroinflammation."There's been literature suggesting that patients with PTLDS have some chronic inflammation somewhere, but until now we weren't able to safely probe the brain itself to verify it," said co-first author Dr. Jennifer Coughlin, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, in a statement.

"We thought there might be certain brain regions that would be more vulnerable to inflammation and would be selectively affected, but it really looks like widespread inflammation all across the brain," she noted.

The results suggest that drugs designed to curb neuroinflammation may be able to treat PTLDS; however, clinical trials are needed to determine the safety and benefit of such therapy, according to the researchers.