MR images have shown that teenage girls who are prone to injuring themselves have reduced brain volume in two regions. The results suggest the root of the self-harming actions is also biological, rather than solely behavioral, according to a study published online November 5 in Development and Psychopathology.

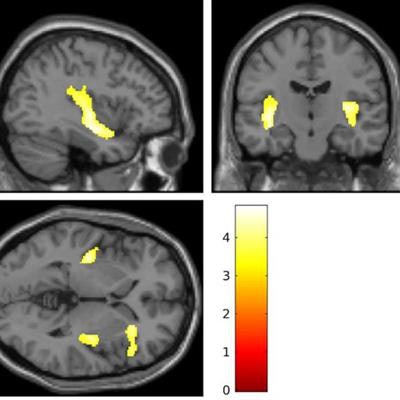

Researchers performed MRI brain scans on 20 teenage girls who had a history of severe self-injury, such as cutting, and 20 girls with no history of self-harm. The scans revealed clear reductions in volume in the insular cortex and inferior frontal gyrus among the 20 self-injuring girls, compared with those in the control group.

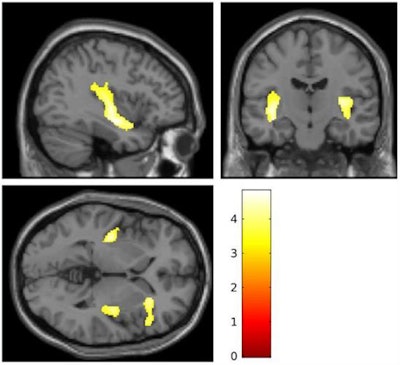

The affected brain regions in the self-injuring girls were similar to abnormalities seen in adults with borderline personality disorder, which is also more common in women.

Images show brain regions where researchers saw reductions in brain volume in girls who self-injure. Courtesy of Ohio State University.

Images show brain regions where researchers saw reductions in brain volume in girls who self-injure. Courtesy of Ohio State University.The findings are especially important given recent increases in self-harm in the U.S., which currently affects as many as 20% of adolescents and is being seen earlier in childhood.

"Girls are initiating self-injury at younger and younger ages, many before age 10," said lead author Dr. Theodore Beauchaine, a professor of psychology at Ohio State University, in a statement from the university.

Cutting and other forms of self-harm often precede suicide, which increased by 300% among 10- to 14-year-old girls from 1999 to 2014, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time, there was a 53% increase in suicide among older teen girls and young women.

Further studies are needed to better understand the relationship between structural differences and self-harm and how the differences might correspond with progression to borderline personality disorder and other mental disorders, Beauchaine said.

"If we can learn more about how adults with psychiatric disorders got there, we are in a much better position to take care of people with these illnesses, or even stop them from happening in the first place," he said.