At this week's Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) meeting in Atlanta, physicians from Louisiana will discuss their use of 3D printing to construct drug-delivery tools to fight infection and even cancer in the interventional radiology suite.

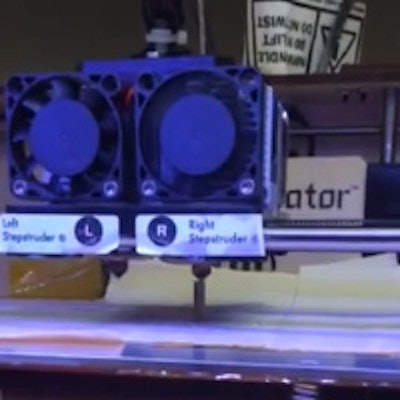

Using a 3D printer and resorbable bioplastics, the group built bioactive interventional radiology devices that deliver medication to targeted areas of the body. In the process, they used antibiotic-containing catheters to inhibit bacterial growth, as well as filaments with therapeutic agents to halt cancer growth in cell cultures.

"Although these successes are early successes, we believe that our findings with this technology highlight the limitless potential of interventional radiology to offer patient-centered care," said Dr. Horatio D'Agostino in a teleconference prior to the SIR meeting.

These systems give doctors the ability to construct devices that meet patient needs based on their own unique anatomy and specific medical requirements, said D'Agostino, who is chair of radiology and director of interventional radiology at Louisiana State University (LSU) Health Sciences Center. He conducted the study with a team of biomechanical engineers and nanosystem engineers at LSU and at Louisiana Tech University.

The researchers aimed to create user-customized devices that could deliver medication to a particular area, D'Agostino said.

"Using 3D printers and bioplastics, our team constructed filaments, leads, catheters, and stents that contained either antibiotics or chemotherapeutic agents," he said. "These fabricated devices would be able to deliver active medication to a targeted area."

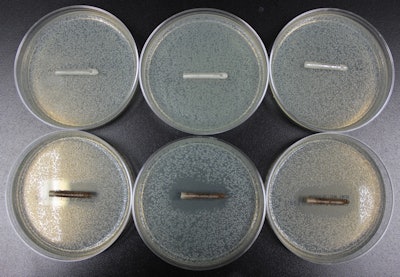

The team tested the devices in cell cultures and found that they did, indeed, inhibit bacterial growth. The study team also saw that filaments with chemotherapeutic agents were able to inhibit the growth of cancer cells.

E. coli bacterial colonies on agar plates. Top row: 3D printing of standard plastic catheters. Bottom row: 3D printing of a bioplastic catheter infused with 1% gentamicin antibiotic. All images courtesy of Dr. Horacio D'Agostino.

E. coli bacterial colonies on agar plates. Top row: 3D printing of standard plastic catheters. Bottom row: 3D printing of a bioplastic catheter infused with 1% gentamicin antibiotic. All images courtesy of Dr. Horacio D'Agostino."We found that the antibiotic-containing catheters were able to inhibit the growth of E. coli in the lab," D'Agostino said. "We also saw that growth of osteosarcoma cells, or bone tumor cells, was inhibited by filaments carrying therapeutic agents in cell cultures."

LSU treats a wide variety of patients, so one-size-fits-all devices are not an option, D'Agostino said in a statement accompanying the presentation. 3D printing "gives us the ability to craft devices that are better suited for certain patient populations that are traditionally tough to treat, such as children and the obese, who have different anatomy," he said.

The findings highlight the nearly limitless potential of interventional radiology to offer patient-centered care, D'Agostino said in his talk.

"Within a few years, interventional radiology will be able to print catheters and stents almost on demand, in sizes and shapes that are customized to each patient," he said. "Our data show that clinicians will also be able to put active medications into these tailored devices to deliver medication in a precise and targeted manner. We also see an opportunity to collaborate with other medical specialties to ensure that all patients benefit from this innovative technology and receive the highest quality of personalized care."