Babies whose mothers took medication to control their depression were found to have significantly more gray matter on MRI scans in several brain regions than infants whose mothers did not receive medication for their condition, according to a study published online April 9 in JAMA Pediatrics.

The differences were noted on structural and diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI-MRI) in the right amygdala, right insula, and right caudate, which are associated with emotional processing, in women who took selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications. There also was an increase in white-matter connection strength between the amygdala and insular cortex.

"Based on our study and those of other researchers, we can say with some confidence that SSRI medications have an influence on fetal brain development," said corresponding author Jiook Cha, PhD, an assistant professor of neurobiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute. "Exactly what that influence means over the longer term with regard to the infant's cognitive and emotional development remains unclear and requires subsequent research to really understand."

SSRIs and maternal depression

Jiook Cha, PhD, from Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Jiook Cha, PhD, from Columbia University Irving Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.The use of SSRIs to control prenatal maternal depression (PMD) has been on the rise over the past 30 years, most likely due to increased awareness of the potential effects on both mothers and their children if the depression is not treated.

Serotonin is an important neurotransmitter, but its effects are more broadly spread in a fetal brain compared to an adult brain, Cha explained in an email to AuntMinnie.com. Animal studies have found that serotonin plays an important role in initial brain development during the fetal period.

As for humans, it is known that when pregnant women use SSRIs, the serotonin levels in their brains increase. Previous studies have shown mixed results in terms of the associations between maternal SSRI use during pregnancy and an infant's brain and cognitive development.

"What is unknown is whether and to what extent serotonin levels within the fetal brains change in response to prenatal exposure to SSRI," Cha said. "If there is no change, it is possible that prenatal exposure to SSRI has no effects on fetal development. If there is a change, it is possible that prenatal exposure to SSRI has an effect on fetal development. Our study supports the latter case; on the other hand, some prior studies support the former."

Scanning protocol

Between January 2011 and October 2016, the researchers collected data from 98 infants. Among the subjects, 16 babies were exposed to their mothers' SSRI medication in utero and 21 were born to mothers who experienced maternal depression but were not treated for the condition. The study also included 61 healthy controls for comparison (JAMA Pediatr, April 9, 2018).

Structural and diffusion-weighted images were acquired on a whole-body 3-tesla scanner (Discovery MR750 3T, GE Healthcare) with an eight-channel head coil. The protocol included one scan with T2-weighted structural MR and two runs with diffusion-weighted imaging. The 98 infants had a mean age of 3.43 (± 1.50) weeks at the time of the scans.

Voxel-based morphometry results showed significant gray-matter volume expansion in the right amygdala (Cohen d = 0.65) and right insula (Cohen d = 0.86) among infants exposed to their mother's SSRI, compared with both the healthy controls and infants exposed to untreated maternal depression (p < 0.05).

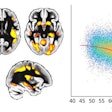

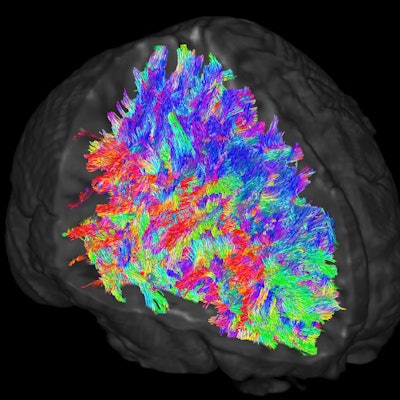

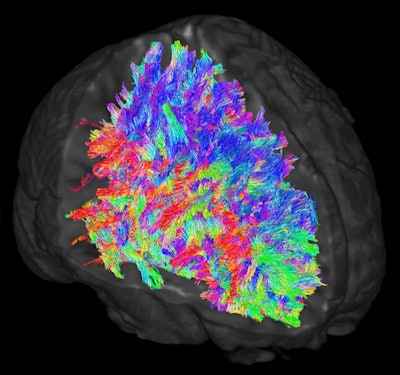

Images illustrate white-matter tracts estimated through DWI-MRI and tractography. Wiring patterns within the brain are thought to vary across individuals. The colors represent the directions of the white-matter tracts.

Images illustrate white-matter tracts estimated through DWI-MRI and tractography. Wiring patterns within the brain are thought to vary across individuals. The colors represent the directions of the white-matter tracts.In addition, the connectome-level analysis of white-matter structural connectivity revealed a significant increase in the SSRI-exposed group between the right amygdala and the right insula (Cohen d = 0.99), compared with the healthy controls and babies whose mothers were not treated for depression (p < 0.05).

MRI showed no brain regions in which there were decreases in gray-matter intensity in the babies exposed to SSRIs. There also were no significant differences in gray-matter volume between the infants whose mothers were not treated for depression and the healthy control babies.

Questions remain

While the findings shed light on the issue of SSRIs and fetal brain development, Cha and colleagues are quick to note that more research is needed to provide definitive conclusions.

"An important take-home message from our study is that there are still a lot of unanswered questions about the effects of maternal SSRI use during pregnancy, and additional research is sorely needed," Cha said. "It is very difficult to imagine that a single study can demonstrate the complex impact of prenatal exposure to SSRI, maternal depression, and an interaction between the two on fetal development, as well as long-term brain and cognitive development."

Thus, there remains no easy answer when balancing treatment for the mother's condition and the potential outcome for the baby.

"Whereas potential SSRI effects on fetal brain development are concerning, maternal depression is also an important factor that influences the fetus and the mother," he said. "Maternal depression increases the risk for negative pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight and prematurity. It can also lead to postpartum depression with effects on mother-infant bonding."

So how should women handle prenatal depression? Cha emphasized that treatment is very important.

"Several options are available, including medications and psychotherapies," he said. "Deciding which treatment option is the best for any individual patient is a decision between that patient and her doctor. The pros and cons of the treatment options need to be considered in the context of the individual patient. More rigorous scientific research is required to aid such decisions."