Using PET imaging, researchers at Washington University have found that welders exposed to manganese fumes in their jobs are at risk of serious brain injury and loss of motor skills, according to a study published online April 6 in Neurology.

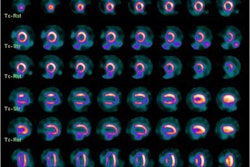

PET scans showed reduced fluorine-18 FDOPA uptake in parts of the basal ganglia, which is associated with cognition, memory, and movement, as well as Parkinson's disease. The decreased FDOPA uptake may be an early sign of manganese neurotoxicity and differs from the pattern of dysfunction found in symptomatic Parkinson's disease patients, the researchers noted.

The lead author of the study is Dr. Susan Criswell, an assistant professor of neurology at Washington University.

The study is part of a larger epidemiology study Washington University researchers have been conducting for the past six years, investigating a potential link between welding and Parkinson's-like symptoms in healthy, active workers -- individuals not expected to have Parkinson's disease.

"The group that we studied [had] a mild motor slowing that was characteristic of the welders we have seen over the years," said study co-author Dr. Brad Racette. "We thought this was an ideal population to study, because the likelihood that they would have Parkinson's disease was actually remote. We were trying to understand if there were changes in the brain that occurred and if they were associated with welding exposure."

The researchers recruited 20 welders with no symptoms of Parkinson's disease from two Midwest shipyards and one metal fabrication company. The study also included 20 nonwelders who had Parkinson's disease, and 20 nonwelders with no evidence of Parkinson's disease.

The 20 welders had mean lifetime exposures of 30,968 hours, ranging from approximately 4,000 hours to 56,000, and average manganese levels twice the upper limits of normal. The researchers excluded welders with fewer than 100 hours of welding exposure or those who had comorbid neurologic disease.

All participants underwent brain PET studies (ECAT Exact HR+, Siemens Healthcare) and MRI scans (Magnetom Symphony, Sonata, Trio; Siemens), as well as motor skills tests. A neurologist who specializes in movement disorders evaluated the images and motor skills results.

Parkinson's symptoms

Typically, patients with Parkinson's disease exhibit a loss of dopamine cells in the basal ganglia region of the brain. Dopamine stimulates cognition, memory, and movement and helps neurons connect and communicate in the basal ganglia. PET imaging with FDOPA can measure dopamine activity in the region.

"Our hypothesis was that if these welders have this chronic exposure [to manganese] and if there is a relationship with Parkinson's disease, we might see some early reductions in FDOPA uptake, suggesting damage to those dopamine neurons," Racette said.

In the PET images of the basal ganglia, the researchers found graded reductions in signal, which corresponds with reduced FDOPA uptake and is characteristic of Parkinson's disease.

Welders exhibited a 12% reduction in FDOPA uptake, compared with those in the normal control group. "Normal subjects have the normal [FDOPA] uptake as we expect, but the welders had evidence of a problem with the dopamine system in a pattern that seemed different than what we see in Parkinson's disease, but clearly abnormal," Racette said.

FDOPA PET patterns

In subjects with Parkinson's disease, FDOPA uptake in the basal ganglia showed a decrease compared to normal control subjects, with the greatest reduction in the posterior putamen.

By comparison, FDOPA uptake in the welders was most affected in the caudate, followed by the anterior putamen and the posterior putamen; this pattern was anatomically reversed from the pattern demonstrated in Parkinson's disease patients.

"There are a lot of things that need to be done to investigate the role of manganese in Parkinson's disease, but the most important finding is that these people who are chronically exposed to manganese in the workplace have evidence of brain injury," Racette said.

Racette and colleagues plan to continue the research by following up imaging exams of the approximately 900 workers in the entire epidemiology study.

"We clearly need to repeat scans in these people," he added. "Following them would be a very good way to address the relationship with Parkinson's disease. More importantly, is there a progression of this, and does this look like a degenerative condition?"

The study was supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the American Parkinson Disease Association (APDA), the Advanced Research Center at Washington University, the Greater St. Louis Chapter of the APDA, the McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function, and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.