Radiologists can assess skeletal age on hand radiographs faster and more accurately with assistance from an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm, according to a prospective analysis published online September 28 in Radiology.

A group of researchers led by David Eng of Stanford University trained a deep-learning algorithm and then conducted a prospective and randomized multicenter controlled trial to evaluate its performance across six different sites. Although results varied among the centers, AI yielded an overall improvement in speed and accuracy.

"Taken together, these findings support careful consideration of AI for use as a diagnostic aid for radiologists and reinforce the importance of interactive effects between human radiologists and AI algorithms in determining potential benefits and harms of assistive technologies in clinical medicine," the authors concluded.

Although prior studies in the literature have suggested that AI could enhance the quality of skeletal age assessment, the researchers sought in their study to determine -- using a superiority trial design -- if AI could improve diagnostic accuracy and lower reading times for radiologists.

"Evaluation of the algorithm in representative clinical conditions would advance understanding of its true benefits and harms (i.e., deferral to an inaccurate AI interpretation or overriding an accurate AI interpretation)," the authors wrote.

After training a deep-learning algorithm using open-source training data from the RSNA Pediatric Bone Age Machine Learning Challenge, the researchers then recruited 93 radiologists at six centers to assess bone age on hand radiographs without AI in 739 cases and with AI in 792 cases.

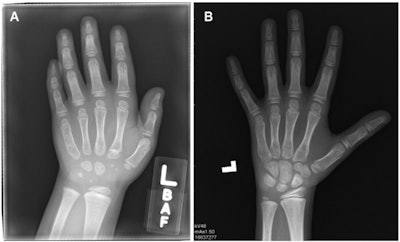

Sample examinations in the study. (A) Computed radiograph in a girl randomly assigned to the control group at center 2 with low AI error and high radiologist error (AI = 46 months, chronologic age = 76 months, radiologist = 69 months, panel = 41 months). (B) Computed radiograph in a boy randomly assigned to the control group at center 4 with high AI error and low radiologist error (AI = 126 months, chronologic age = 140 months, radiologist = 105 months, panel = 100.5 months). Images and caption courtesy of the RSNA.

Sample examinations in the study. (A) Computed radiograph in a girl randomly assigned to the control group at center 2 with low AI error and high radiologist error (AI = 46 months, chronologic age = 76 months, radiologist = 69 months, panel = 41 months). (B) Computed radiograph in a boy randomly assigned to the control group at center 4 with high AI error and low radiologist error (AI = 126 months, chronologic age = 140 months, radiologist = 105 months, panel = 100.5 months). Images and caption courtesy of the RSNA.The study sites included the following: Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, New York University School of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, and Yale University School of Medicine.

The radiologists' results were compared with a reference panel of four experts. Overall, use of AI led to a smaller difference in skeletal age compared with the reference panel.

| Impact of AI on accuracy of bone age assessment | ||

| Radiologists without AI | Radiologists with AI | |

| Overall mean absolute difference | 5.95 months | 5.36 months |

| Proportions of cases in which absolute difference exceeded 12 months | 13% | 9.3% |

| Proportions of cases in which absolute difference exceeded 24 months | 1.8% | 0.5% |

| Median interpretation time | 142 seconds | 102 seconds |

Although overall diagnostic error was significantly reduced from the use of AI, the researchers noted that accuracy actually decreased at one of the centers. At that location, the researchers observed that radiologists at that location worsened the accurate AI predictions more often than other centers. Radiologists at the outlier site also outperformed radiologists at the other centers.

The study shows that radiology practices embracing AI software must understand that individual behavior can potentially negate the technology's benefits, according to Dr. David Rubin of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

"Remember: Your results may vary," he wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In addition, the actual magnitude of improvement achieved from the AI software was small and unlikely to be clinically relevant, Rubin said. As a result, many practices may not be able to justify adopting this type of AI tool.

"This is especially true in practices with low volumes of requested bone age examinations, where a 40-second savings a few times a day may not be meaningful," he wrote.

He also said that it may be time to move away from using radiologist interpretations as ground truth for training AI algorithms. Large digital databases provide an opportunity to develop AI that can go beyond essentially predicting how radiologists would read an image, according to Rubin.

"Only by shedding the limitations imposed by training using a human-based ground truth can researchers develop applications that will enable clinically relevant forecasts that are currently beyond the abilities of non-AI-aided radiologists," Rubin wrote.