Mucormycosis:

Clinical:

Mucormycosis is the name given to infections produced by fungi in the Mucorales order of the Zygomycetes class. The three agents which are responsible for the majority of infections are Rhizopus and Mucor [8].Six separate forms of infection have been identified: rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, CNS, and disseminated disease. Rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement (30% of cases) are the two most common forms (although other authors cutaneous disease is the second most common site of infection [8]). Paranasal sinus involvement can extend into the orbit or skull base.

The opportunistic infection occurs almost exclusively in certain groups of immune compromised patients including those with hematologic malignancy, stem cell/bone marrow and solid organ transplant patients, immunosuppression diabetics with significant ketoacidosis (growth of the fungi is stimulated by high blood glucose concentration, and infection is rare in patients with well controlled blood glucose levels [8]), renal failure patients, graft versus host disease, and deferoxamine therapy (the majority of risk factors act by impairing neutrophil function) [5,7,8]. Worldwide, diabetes is the most common risk factor (40% overall, but less commonl in Western countries), followed by hematologic malignancy, then organ transplant patients [8]. Some risk factors are more cloasely associated with specific sites of involvement [8]. For instance, solid organ transplant is more uniquely associated with lung infection, whereas diabetes is more closely associated with the rhinocerebral form [8]. In 18% of patients with all types of mucormycosis, no predisposing condition was identified [8].

Patients with pulmonary infection present with symptoms

indistinguishable from a bacterial pneumonia. The clinical course

is rapidly progressive and there is high mortality in immune

compromised patients. Diabetic patients may have a more indolent

course. Pulmonary involvement is characterized by focal

consolidation, arterial thrombosis, and infarction which nodules,

and cavitation (air crescent sign). Additionally, mucor may invade

the walls of larger vessels resulting in pseudoaneurysm formation,

infarction, or hemoptysis. Mucor is among the few pulmonary

infections that may cross pleural surfaces.

Overall mortality is 45-80%, but approaches 100% for those with

disseminated disease. Mucormycosis infection of the

tracheobronchial tree (central airways) has also been described

and is usually rapidly fatal [4]. Effective therapy entails

control of the underlying disease, early surgical removal of

devitalized tissue, and the prompt IV administration of

amphotericin B and, more recently, posaconazole (although most

other azole antifungals such as fluconazole and voriconazole have

no significant activity against mucormycosis [8]) [5]. A delay in

the initiation of amphotericin B-based therapy was associated with

a twofold increase in mortality [8].

Both bronchoscopic and percutaneous lung biopsy are effective in

confirming the diagnosis of mucormycosis [8]. Demonstrating

circulating Mucorales DNA by using quantitative polymerase chain

reaction (qPCR) has been shown to be an effective method for

revealing mycormycosis [8].

X-ray:

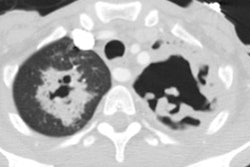

Homogeneous lobar, multilobar, or segmental consolidations are the most common finding on presentation radiographs (up to 47% of cases). A solitary poorly (more commonly) or well defined mass may be the presenting finding in up to 21% of cases. Pulmonary cavitation can occur in up to 40% of cases, but the "air-cresant sign" is less common (12%). Pleural effusions (uni or bilateral) can be found in up to 28% of patients.In early infection, CT may simply show a perivascular ground-glass lesion that will progress to consolidation, nodules, or masses [8]. The "reverse halo sign" (consisting of an area of peripheral consolidation with central ground-glass opacity) can be seen on CT in up to 60% of patients and it is felt to be a specific sign of mucormycosis [6,7,8]. The reverse halo sign is more common in patients with neutropenia compared to those without neutropenia (79% vs 31%) [8]. However, a reverse halo can also be seen in aspergillus infection, as well as bacterial pneumonia, BOOP/COP, paracoccidiomycosis, Wegeners, and sarcoid [6]. Because the fungus tends to invade vasculature, necrosis is a common feature [8]. Cavitation can be seen in about 10% of patients on initial imaging, but ultimately develops in an additional 27% of cases [7]. In imaging series, nodules, masses, or consoliadtion appearing with a CT halo sign progress to a reverse halo sign, followed by central necrosis, and finally, an air crescent sign and this progression was associated with a tendency toward a gradual increased in neutrophil count [8].

REFERENCES:

(1) Semin Roentgenol 1996; Jan 31(1):83-87

(3) J Thorac Imaging 1999; Connolly JE, et al. Opportunistic fungal pneumonia. 14: 51-62

(4) J Thorac Imaging 1999; Kim KH, et al. Mucormycosis of the central airways: CT findings in three patients. 14: 210-214

(5) Radiology 2010; Chung JH, et al. Case 160: Pulmonary

mucormycosis. 256: 667-670

(6) AJR 2014; Walker CN, et al. Imaging pulmonary infection:

classic signs and patterns. 202: 479-492

(7) AJR 2018; Hammer MM, et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis:

radiologic features at presentation and over time. 210: 742-747

(8) Radiographics 2020; Agawal R, et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis:

risk factors, radiologic findings, and pathologic correlation. 40:

656-666