Researchers at Stanford University are working on a dedicated breast MRI coil with smaller coil elements, which they believe could result in sharper images and up to three times the sensitivity of standard MRI coils.

The coil design could prove better suited for following the rapid changes in MRI contrast pharmacokinetics that are key to detecting breast cancer, according to the group. It may also enable faster image acquisition.

"The idea is to have these smaller coil elements so each one will be much more sensitive to pick up much more of the MRI signal," said coil co-developer and assistant professor of radiology Brian Hargreaves, PhD, in an interview with AuntMinnie.com.

Smaller coil array

The device consists of an array of nine small coils placed around each breast. The signal from all 18 coils is measured simultaneously. The key to the technology is being able to place the breast MRI coils as close as possible to suspected tumors.

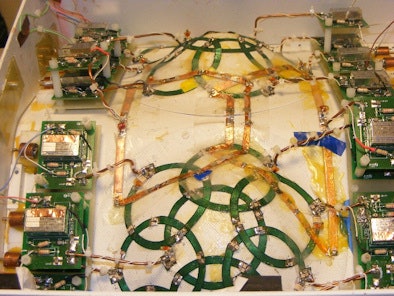

|

| Photo of the coil element placement and electronics. The use of 18 small surface elements allows improved sensitivity and greater use of parallel imaging acceleration. Image courtesy of Anderson Nnewihe, Stanford University. |

While the concept of smaller breast coils is not new to MRI, the design of this specific device is a novel approach, according to Hargreaves, whose background is in electrical engineering. Radiologist Dr. Bruce Daniel, who has been working with breast MRI for some 15 years, is also working with Hargreaves on the technology.

Preliminary indications are that the breast coil is approximately three times more sensitive than other standard coils. In theory, Hargreaves said, MR images could be obtained three to four times faster.

"We are able to image more quickly with multiple coil elements," Hargreaves said. "This helps, because we want to get sharper images, but we also want to get them more quickly so we can see the contrast dynamics changing."

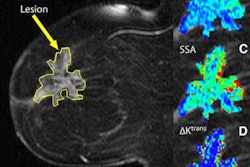

Image timing

Because Stanford researchers are using a dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI protocol, timing the MRI scan is critical. Blood gets to cancerous tumors quickly because these tumors are highly vascularized. With the injection of a gadolinium-based contrast agent, MRI can identify flow in the tumor.

"If we can scan quickly enough, what we see is the contrast agent getting to the tumor much more quickly than it gets to normal tissue," Hargreaves said.

"The key is to image quickly enough so that we can identify the tumor," he said. "If we image too soon, [the contrast agent] hasn't gotten to anything yet, and if we image too late, [the contrast agent] gets to everything. What we want to do is to be able to identify how the image changes over time after we have injected the contrast agent."

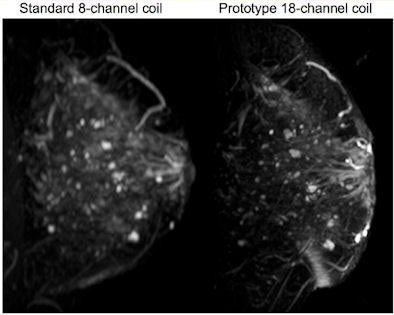

|

| Images utilizing a standard coil and the custom coil, with scan times of four minutes. The vessels and other structures are much more clearly visualized with the 18-channel coil than the standard coil. Image courtesy of Catherine Moran, Stanford University. |

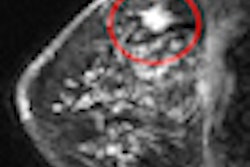

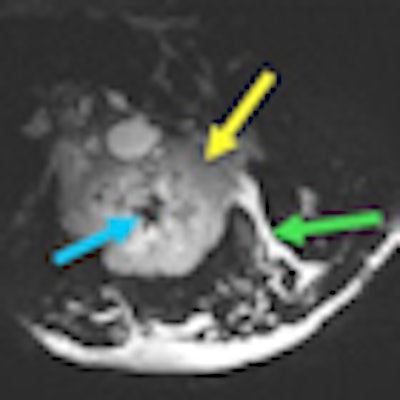

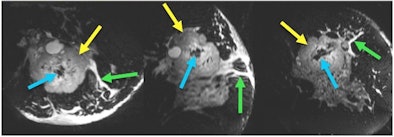

|

| 3D T2-weighted images acquired with the prototype 18-channel breast coil in four minutes from a patient with a locally advanced biopsy-proven invasive ductal carcinoma (yellow arrows). Fine morphological detail, including central low-signal fibrosis (blue arrows) and edema (green arrows), are depicted clearly in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. Image courtesy of Stanford University. |

A better fit

While the smaller coil design is not completely unique compared to coils offered by current manufacturers, the Stanford researchers are taking a different approach by designing the breast coil so it is much closer to the patient.

"That's where this is a bit of a science experiment, because the coils will not fit every patient," Hargreaves said. "Women have different sized breasts; if it works really well, maybe we will have to develop different sizes for different people."

So far, the group has tested only approximately 30 healthy women whose breasts fit the current coil size to evaluate how well the technology will improve diagnosis. "Assuming we are successful there, we will need to figure out a way to make it fit everybody," Hargreaves said.

Hargreaves emphasized that it is too soon to conclude how well the breast coil will work. He and his colleagues plan to test the technology on more patients, hoping to get at least another 50 or so subjects over the next 18 months.

| The majority of the research has been funded through a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Stanford researchers have also been working with and have received a research grant from GE Healthcare, which supplies the MRI equipment. A pending patent has been licensed to both GE and Siemens Healthcare. |