Low-dose whole-body radiographic systems were initially designed to rapidly image critically injured emergency and trauma patients. But sites with the systems are finding that they can be useful for performing rapid bone survey screenings of cancer patients, saving time and radiation dose for patients.

The screenings are a practical way to increase the utilization of these systems and also dramatically decrease the amount of radiography room and technologist time spent if a conventional radiographic survey were performed instead.

The University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) in Baltimore and Washington Hospital Center in Washington, DC, both level I trauma centers, routinely use low-dose whole-body radiographic systems (Statscan, Lodox Systems, South Lyon, MI) for this application. The results of a UMMC study comparing the system's accuracy in identifying bone metastases of cancer patients with standard radiographs, CT exams, MRI exams, and PET/CT exams were published in a recent issue of Cancer Investigation (November 2008, Vol. 26:9, p. 916-922).

The paper reports the study findings of Dr. Michael Mulligan, an associate professor of radiology and nuclear medicine at UMMC, and colleagues, as well as the experiences of Washington Hospital Center as described by its radiology department chairman, Dr. James Jelinek, to AuntMinnie.com.

Patients with cancer, multiple myeloma, and other malignances often need screening studies of the entire skeleton to determine the presence of metastatic disease or multifocal involvement. Radiography bone surveys are initially performed as the first exam because x-ray equipment is readily available and inexpensive compared to nuclear scintigraphy and PET/CT exams.

If metastases are identified anywhere in the skeleton with the initial bone survey, additional diagnostic imaging procedures may not be needed because treatment decisions are not as dependent upon knowing each specific site of involvement, according to Mulligan. But if metastases are suspected and not identified on the radiograph, exams with higher sensitivity will be ordered.

The researchers identified all cancer patients who had scans performed over a 12-month period and found 99 exams, of which Statscan was used for 35. Five patients were eliminated from the study because they had not had at least one other bone imaging study performed within 18 months of the low-dose whole-body radiographic procedure.

Eighteen of the patients had been diagnosed with monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS)/multiple myeloma, 11 patients were diagnosed with various primary cancers, two patients had lymphoma/leukemia, and one patient had both MGUS and renal cell carcinoma.

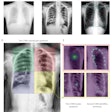

Three radiologists, representing inexperienced, experienced, and highly experienced musculoskeletal specialists, independently reviewed the Statscan-generated images. They recorded the location and number of osteolytic and/or osteoblastic lesions they identified, and rated each image as being of diagnostic, marginal, or nondiagnostic quality. They also recorded the number of images for each patient.

Thirty days later, the radiologists reviewed all the other relevant imaging studies for the 30 patients, also noting the location and number of lesions they saw. For conventional radiography bone surveys, they recorded the number of images generated for each patient.

Images generated from the low-dose whole-body radiographic system proved to be comparable to images produced by other modalities for the purpose of identifying bone lesions in 19 patients. The studies of 11 patients, no matter what modality was used, were interpreted by all three radiologists as normal.

A total of 117 lesions were identified by all three radiologists from Statscan exams on 19 patients; 96 lesions were osteolytic and 21 were osteoblastic. A total of 106, or 90%, of the 117 lesions were confirmed as areas of suspected metastatic disease or multifocal involvement by the other imaging studies. Seven were confirmed by standard radiographic bone survey, 33 by CT, 13 by MRI, eight by PET/CT, and four by bone scan. These exams were performed between one day and 18 months from the time the Statscan exams were performed, averaging 3.5 months.

The radiologists' opinion of the quality of the low-dose whole-body radiographs varied based on their experience, with more experienced readers rating the images as good:

|

Many patients who require bone survey screening are fragile and feel ill and exhausted, Mulligan told AuntMinnie.com in an interview. The low-dose whole-body scans take an average of three images in a five-minute time period. By comparison, performing the procedure with conventional x-ray or computed radiography takes 25 to 45 minutes for the typical patient because eight to 20 different exposures may be needed. There are other benefits as well.

"The additional benefit for the patient is a 25% to 75% lower radiation dose," Mulligan said. "For our hospital, this type of scan makes better use of our technologists' time and also doesn't tie up our x-ray rooms, which can be quite busy. We have never yet had an incident when a trauma patient needs to be imaged at the same time as one of our cancer patients."

The billing cost is the same for either a conventional radiography scan or a low-dose whole-body scan. When technologist time and opportunity cost for the use of the x-ray room are factored in, the low-dose whole-body scan is more cost-effective to use.

This is certainly reflected by UMMC's use of the system, which went into operation for cancer patients in March 2006. Between July and December 2006, 46.9% of the cancer/myeloma bone surveys were performed using the Statscan unit. The following year, usage had increased to 90.4% of surveys for the same six-month period, and usage had increased to 97.3% in 2008.

Washington Hospital Center purchased its Statscan unit in 2002 for use with its trauma patients. Last year, approximately 70 patients were scanned with it each month, with seven typically representing cancer patients, according to Jelinek.

"I think we see metastases and myeloma better with these images than with standard x-ray images," Jelinek said. "The penetration of the Statscan is better than average x-rays. We use the system for patients who have multiple myeloma, especially if they have a fracture."

The time savings for both the patient and the department are huge, according to Jelinek. "It can take a good 45 minutes to do a complete skeletal survey on an inpatient who is elderly or in pain from a pathologic fracture. The technologist can put the patient supine and do a total-body AP view in 13 seconds. Then, without moving the patient, the technologist can get a total-body lateral view in 13 more seconds. It might be necessary to repeat a view like the skull in high resolution, but that also takes only seconds," he said.

Both Mulligan and Jelinek believe that radiologists and referring physicians should be as confident with the whole-body system as with a conventional radiographic exam, and that hospitals who own these systems may find it beneficial to use them for bone survey screenings and for use with trauma patients.

By Cynthia E. Keen

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

March 20, 2009

Related Related

Studies examine digital methods for reducing pediatric x-ray dose, October 9, 2007

New progress in multiple myeloma treatment: MDCT has edge in detection, June 18, 2007

F-18 fluoride PET/CT accurately detects bone metastases in high risk prostate cancer, March 10, 2006

Copyright © 2009 AuntMinnie.com