Doctors rarely tell parents about the radiation risks associated with CT imaging of pediatric patients, and understandably so. Time is in short supply. The subject is complex, potentially troubling for parents, and could lead to overconcern -- even to the detriment of necessary imaging exams.

But a pilot study in Colorado found that parents can be easily educated about radiation risks with the aid of a short brochure -- and that they react quite well to what they learn. Knowing CT scans aren't risk-free might even reduce some of the demand for CT in situations where it might not be needed, according to the researchers.

At the 2006 RSNA meeting in Chicago, Dr. David Larson from the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver talked about the ongoing initiative, which appears to have been successful in educating parents whose children are referred for non-emergent CT scans. Emergency departments are expected to be included as the study expands.

The growing use of CT in children has led to increasing radiation doses delivered to pediatric patients; several studies have shown that patients and parents are generally unaware of the risks and radiation associated with CT exams, Larson said.

"Also, there is anecdotal evidence that suggests that patients and parents may contribute to the demand for CT, and this is especially concerning given the lack of awareness of the risks," he said. "Our hypothesis is that by informing parents of risks associated with CT, we might help to reduce this demand, especially if alternatives are available. But there's also a legitimate concern that this may overly concern some parents, and may actually talk some parents out of doing CT when it is appropriately indicated."

The study sought to determine how a brief handout about CT would affect parents' understanding of the radiation and the cancer risk associated with CT, Larson said. The researchers also wanted to know how the brochure would affect parents' willingness to let their children be scanned when necessary, and how it would affect their willingness to consider an alternative to CT "in a hypothetical situation where observation would be available as an alternative," Larson said.

The study participants were the parents of pediatric outpatients who were referred to a children's hospital. Emergency department patients were excluded for this stage of the study.

"We did the study by giving an initial survey, we gave them the informational handout, then we administered a final survey," Larson said. The administrative staff ran the study, but parents could speak with a radiologist if they had any questions, he added.

The two-page brochure briefly describing radiation and risk took less than five minutes to read at an eighth-grade level. The handout compared radiation doses in common scans to typical exposure factors, such as air travel.

The group then provided quantitative risk estimates to patients using a 2001 study on head scan risk estimates, and extrapolated it based on typical doses given to the facility's pediatric population, Larson said.

For example, a 1/3,000 lifetime attributable risk of cancer from an abdominal CT scan was added to the baseline cancer risk of 700/3,000 for a typical pediatric patient who does not undergo CT. The brochure explains that a single abdominal scan increased the lifetime risk of developing cancer from 700/3,000 to 701/3,000, Larson said.

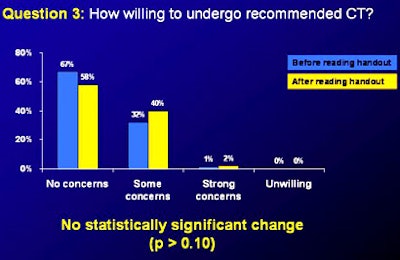

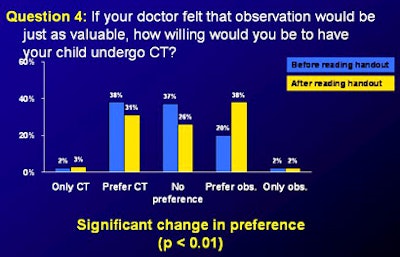

Of the 52 parents surveyed, before reading the brochure 66% believed CT uses radiation, versus 99% afterwards (p < 0.01), Larson reported. Before reading the brochure 13% believed CT increases the lifetime risk of cancer, versus 86% afterwards (p < 0.01). After reading the brochure, parents became slightly less willing to have their child undergo CT if their doctor felt that either CT or observation would be equally effective (p = 0.02), but their willingness to have their child undergo a CT scan recommended by their doctor did not significantly change.

"No parent was unwilling to allow child to undergo CT after reading this handout," Larson noted.

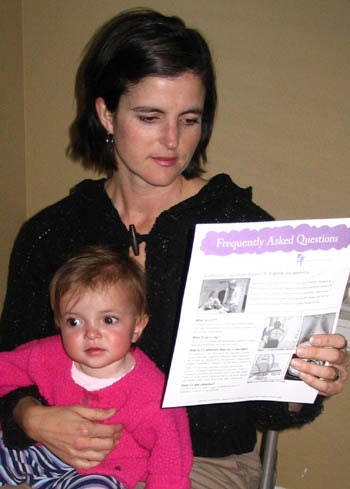

|

| A parent reads the brochure about radiation risks in children. Image courtesy of Dr. David Larson. |

The last question asked about parents' willingness to skip CT if the child's doctor thought observation would be just as valuable. Before reading the brochure, most parents either preferred CT or had no preference; after the handout most preferred observation.

Just one parent asked to speak to the radiologists to clarify some information, Larson said.

"In conclusion we found that a brief informational handout takes little time of parents," Larson said. "We found that it is effective in helping parents understand at least the basics, that CT does use radiation and increases the risk of cancer. And we found that it does not dissuade parents from allowing a child to undergo CT when appropriate, nor does it frighten them or make them overly concerned."

The idea for the brochure came up when emergency department doctors called radiology looking for ways they might dissuade parents who came in insisting on CT scans for their children that the doctors felt were weren't clinically indicated, or only marginally indicated, Larson said.

|

| Learning about the radiation risks of CT in the brochure did not make parents less likely to allow their children to be scanned when necessary (top). After reading the material, however, parents were more likely to consider observation when the physician felt it would be just as valuable as CT (bottom). The results suggest that education may help wean parents away from demanding CT scans of dubious clinical utility. Charts courtesy of Dr. David Larson. |

|

Larson's RSNA audience was enthusiastic about the handout, with a couple of attendees suggesting that the group make it available to everyone -- and especially in referring physicians' offices where most scanning decisions are made. Larson said the brochure will be made available to referring physicians, but for the initial feasability study the researchers wanted optimal control of the study conditions.

As for determining which CT scans might be skipped, "we are going to try to define what is marginally indicated without causing too much controversy," Larson said.

A PDF version of the brochure will be published soon and will be available for download, Larson told AuntMinnie.com.

By Eric BarnesAuntMinnie.com staff writer

December 28, 2006

Related Reading

Work-hour limits for pediatric residents tied to fewer errors, December 5, 2006

Major changes in the radiology residency program requirements are coming, December 5, 2006

Childhood leukemia, brain tumor survivors at risk for stroke, December 1, 2006

Radiologists can misinterpret children's lung nodules at CT, May 16, 2006

Pediatric CT won't stop growing, but dose can be minimized, May 8, 2003

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com