Getting women to take advantage of nationwide breast cancer screening programs is a big job, even in smaller countries. However, small size does offer several advantages to implementing a comprehensive program, which the creators of BreastScreen Singapore (BSS) utilized to their nation's benefit.

"Singapore is a Southeast Asian island city-state with 4 million residents and three major racial groups," said Dr. Shih-Chang Wang at the European Congress of Radiology (ECR) in Vienna, Austria, this month. "It's approximately 683 sq km in size."

Wang is from the department of diagnostic radiology in the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine at the National University of Singapore, and he presented the structure of the BSS program, its results, and the challenges facing the program's architects and personnel.

Some of the virtues of developing a screening program for a small place are that the demographics are well known, the population is stable, and implementation is more controllable, Wang said. In addition, Singapore has in place a national ID system and a national cancer registry.

Traditionally, he said, the incidence of breast cancer in Asia has been low; however, it is increasing in the region with a peak incidence in middle-aged women. Singapore, he noted, has the highest breast cancer rate in Asia.

"There are few screening programs and low community awareness," Wang observed.

Singapore launched BSS in January 2002. To date, it is the only government-funded Asian breast screening program, and the only co-payment breast screening program in the world, he said.

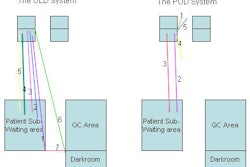

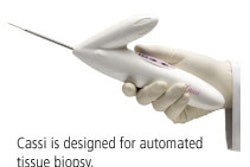

The program utilizes centralized dual readers in consensus (with a third reader in case of arbitration) for all its mammograms and a protocol-based pathway, and provides for stringent case reviews. Multidisciplinary reviews of radiology/pathology are conducted on a weekly basis; difficult and interesting cases, processes and issues, and statistics and updates are conducted every two months; and a national conference is held every 12-18 months.

Women between the ages of 50 and 64 are invited to participate biannually, while women between the ages of 40 and 49 are eligible for yearly screening. All data pertaining to patient encounters are entered into a national Web-based database, which enables better service and data analysis than a paper-based system, Wang said. The interactive forms mimic paper except that they incorporate prompts and notifications as well as error-checking features.

The program arguably has one of the best quality assurance and information technology systems of any national breast cancer screening program. BSS makes every attempt to close the loop on each patient screened. Incomplete data are checked, final diagnoses are entered into the database and shared with the Singapore cancer registry, and audit and performance statistics are generated.

As of March 2005, Wang said that 177,932 screens have been performed with a recall rate of 8% to 10% and a malignancy detection rate between 0.4% and 0.56% during that time. Of those malignancies, 26% to 33% have been ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

"We've learned that screening mammography is very effective in Asians," he said. "The recall, biopsy, and detection rates are equivalent to those of Western nations."

Wang, who also serves on the BSS quality assurance committee, noted that screening dropped off in 2005. In fact, there has been an extremely low response rate to screening invitations issued by BSS; of the women screened by the program, more than 70% have not been invited, he said. The result has been very low compliance and return rates.

According to Wang, studies on Asian women's breast cancer perceptions in California, London, and Singapore have found that they fear pain, radiation, and cancer; do not understand regular screening; are unaware of potential cures; see their personal risk as low; and have a fatalistic attitude toward disease.

BSS has found that community education in multiple languages is needed to overcome what is still a taboo subject in Singapore. General practitioner recommendations for mammographic screening are effective, but most Singaporeans do not have a general practitioner, Wang said. In addition, there is no well-established women's press in the country, and there are, as yet, no celebrity role models that have taken up the cause of breast cancer screening.

The lesson that BSS has learned in its first few years of implementation is that public education is crucial to the success of a national screening program. Various challenges reduce participation and compliance but these can be mitigated, Wang said.

"Build it, but teach them to come," he said.

By Jonathan S. Batchelor

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

March 24, 2006

Related Reading

Scandinavian studies take mammography to task once again, March 3, 2006

Bollywood-style song inspires U.K. women to get mammograms, February 10, 2004

Chinese women respond best to doctors' breast cancer screening advice, February 19, 2003

Breast cancer rates for Asian-American women climb, June 12, 2002

'Western' risk factors for breast cancer do not seem to hold in India, June 12, 2002

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com