SAN FRANCISCO - In case you had any doubts, technology and urgent care practice are increasingly headed toward a single conclusion: CT is all you need to image neurological injuries, including the head, the spine, and even ligamentous trauma.

In application after application, the imaging alternatives simply haven't kept up. And CT has also been aided -- for better or worse -- by the fast pace, high volume, and litigious nature of medical practice in the U.S.

This week at the Society of Critical Care Medicine meeting Dr. Heidi Frankel, associate professor of surgery and chief of critical care at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, discussed what trauma docs and the literature say about who needs or doesn't need a head or spine CT, and who needs another type of imaging exam (hint: very few).

Bumps and boo-boos

So who needs their head examined? In today's medicolegal climate, just about anyone with a bump on the head. Sometimes the indication for head CT is quite obvious.

"Clearly patients who are in coma, or even those with what was called in the past 'moderate' head injury (GCS [Glasgow Coma Scale] score of 9-12) merit having a CT head scan to make sure there's nothing you're going to do something about," Frankel said.

With head injury patients, CT reliably excludes space-occupying lesions and guides monitoring decisions. Patients with hemodynamic instability due to torso injury and severe or moderate closed head injury (CHI) should go to the OR first -- and the medical team should consider intraoperative intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring, she said.

Of course, some with very minor head injuries might not require CT, but the imaging bar has been steadily lowered over the years. In the early 1980s, a minor head injury was defined as a GCS score of 13-15, with loss of consciousness for less than 20 minutes.

"But I think we've all come to realize that not all of these are minor head injuries," Frankel said. In 2001, Stein and colleagues examined 1,047 patients with a GCS score of 13 and found that 13% had a positive head CT, 10% of which required treatment (Journal of Trauma, April 2001, Vol. 50:4, pp. 759-760).

Even for lower-risk patients with a GCS score of 15, a meta-analysis of approximately 3,000 patients found numerous risk factors, including severe headache, nausea, or vomiting, that suggest the need for CT. These factors increased the incidence of positive head CT two- to sixfold, Frankel said (Emergency Medicine Journal, November 2002, Vol. 19:6, pp. 515-519).

In practice, however, head CT is pretty much driven by a few sets of guidelines -- which tend to encourage scanning in most cases.

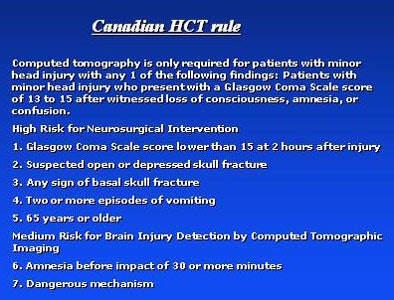

First, the well-known Canadian CT head rule addresses those with injuries with GCS scores of 13-15. Following it would result in 100% sensitivity for neurosurgical interventions, 97.7% sensitivity for the presence of lesions, and 38% specificity. Adoption would reduce CT use by a third (Lancet, May 5, 2001, Vol. 357:9266, pp. 1391-1396).

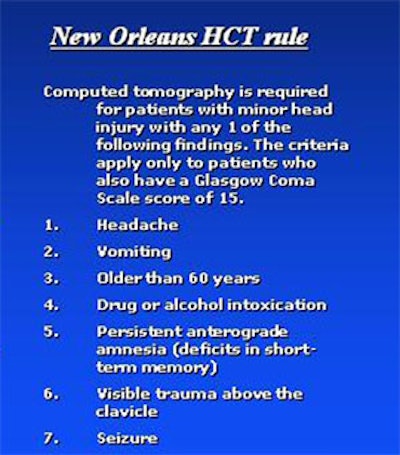

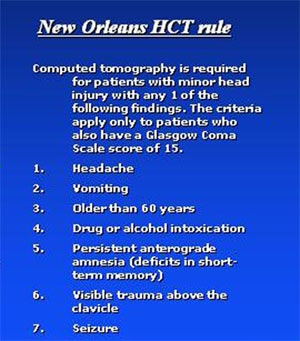

But a meta-analysis that includes the so-called New Orleans rule did a little better, according to Frankel. Following this rule would yield 100% sensitivity for neurosurgical interventions, 99.4% sensitivity for the presence of lesions, and 5% specificity. Its adoption would reduce CT use by just 3% (New England Journal of Medicine, July 13, 2000, Vol. 343:2, pp. 100-105).

The difference between the two? "The Canadians were more interested in saving money, so they had a lot more conservative requirements for CT in their patients," Frankel said. But even though the Canadian rule is effective, 97.7% sensitivity for lesions might simply not be good enough in the daunting medicolegal climate in the U.S. By simply scanning more patients, the New Orleans rule increased the sensitivity to 99%.

"If your patients have concomitant injuries, you're going to be in the scanner anyway, so what the heck, why not fire off the head CT?" Frankel said. "Certainly, the busier your center is and the less chance you're really going to be doing close observations," the more mandatory CT is required for patients with minor head injuries, she said.

|

| Charts courtesy of Dr. Heidi Frankel from data in the Lancet, May 5, 2001, Vol. 357:9266, pp. 1391-1396, and the New England Journal of Medicine, July 13, 2000, Vol. 343:2, pp. 100-105. |

|

On the other hand, follow-up head CT for minor head injuries can usually be skipped -- that is, if you can convince your neurosurgeons to hold off.

"The chance of finding a new lesion on your second head scan that you're going to do anything with is so small as to be next to nil," Frankel said. "And therefore, if you have a patient that comes in to ED and you scan them for indications previously listed, and the head CT is negative and you feel comfortable discharging them otherwise, you can discharge them without another CT."

A study by Kaups et al of 462 slightly more severe head trauma patients (GCS score of 9) found that 18% had a change on the repeat CT scan. Most patients showing a change had either a neurological change or coagulopathy. Of these, 50% needed only another head CT, 40% were monitored, and 10% underwent operative intervention (Journal of Trauma, March 2004, Vol. 56:3, pp. 475-481).

"So if you limited follow-up to either coagulopathic or a neuro change, we could certainly cut down a lot of day-two scans for tiny bumps and contusions," Frankel said. "We don't do it but we could.... It's clear that we overscan patients who have little boo-boos on their head."

Cervical spine

For C-spine trauma, proceed straight to CT, Frankel said. These die were cast in the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) of 34,069 patients. It concluded that CT offers 99.6% sensitivity for the identification of C-spine fractures, with a 12.6% reduction in imaging studies ordered (New England Journal of Medicine, July 13, 2000, Vol. 343:2, pp. 94-99).

NEXUS criteria call for imaging patients with posterior midline tenderness, evidence of intoxication, distracting painful injury, altered level of alertness, or altered neurologic function, she noted.

"It wasn't that long ago when the debate was over one-view, three-view, or five-view C-spine (films) reported at about an 85%, 92%, and 90% sensitivity," Frankel said. Then, for a time, CT was performed only in patients whose films did not show the C7/T1 level. When multislice CT arrived on the scene, it could capture the entire spine faster than plain films could image a portion of it. By the time studies started demonstrating that radiography was in fact far less sensitive than previously reported, C-spine films were finally headed for the dustbin.

Citing a "typical" comparative study by Griffen and colleagues, Frankel noted that radiography missed 35% of fractures -- in these 41 patients, nine required halo vest immobilization and three required operative fixation (Journal of Trauma, August 2003, Vol. 55:2, pp. 222-227).

And in a 2005 meta-analysis comprising seven studies, CT demonstrated 98% sensitivity compared to 52% for radiography, which missed nearly all of the occipital condyle fractures (Journal of Trauma, May 2005, Vol. 58:5, pp. 902-905).

Finally, it appears the NEXUS C-spine rules are applicable to everyone -- even geriatric patients. Touger and colleagues examined 2,943 NEXUS patients age 65 and older. Even though the older patients had more than double the risk of fracture compared to the larger group (4.6% versus 2.2%), nearly the same percentage (14% versus 12.5% for the larger group) had a low risk for C-spine fractures. In this subpopulation, NEXUS rules missed two fractures -- neither of them significant, Frankel said of the study (Annals of Emergency Medicine, September 2002, Vol. 40:3, pp. 287-293).

Ligamentous injuries, too

CT works for ligamentous injuries, which are quite rare, principally because the alternatives for imaging obtunded trauma patients are far worse, Frankel said.

The first alternative, fluoroscopy, is often suboptimal unless it is performed dynamically by flexing and extending the anatomy, in which case it can be risky, she said. Among four studies covering close to 500 patients, "there is a case report of someone who was pithed during this procedure and became a paraplegic," she said.

Questions over who can or will perform fluoroscopy have often led to the second alternative, MRI, which is unacceptable because it overcalls injuries that don't require therapy, Frankel said. According to a study by D'Alise and colleagues, MRI has a false-positive rate of 25% (Journal of Neurosurgery, July 1999, Vol. 91:1 Supplement, pp. 54-59).

"So we've come full circle back to CT scanning," she said. "We realize as the technology improves that even if we're not able to actually see ligamentous injury or the actual disk damage, we can get enough suggestions of swelling and trauma that would prompt us to do MRI in that patient subset. Most of us are stopping at CT; we clear the neck and take the collar off in our obtunded patients based on the CT scan."

Cerebrovascular trauma and carotid vertebral imaging

Three factors have driven the move to CT for blunt cerebrovascular injuries. First, such injuries are fairly common; second, anticoagulation therapy tends to be effective; and third, "patients don't necessarily tend to present with their neurodeficits, but evolve into them over 12 to 24 hours, which allows us the luxury of time to work them up," Frankel said.

Indications of high risk for cerebrovascular trauma include seatbelt marks, hanging or rotatory flexion-extension mechanism, basilar skull or cervical spine fracture, or diffuse axonal injury (DAI). CTA was 70% sensitive in establishing the diagnosis, Frankel said, citing a review article by Dr. Walter Biffl (Current Opinions in Critical Care, December 9, 2003, Vol. 9:6, pp. 530-534).

A Journal of Trauma study currently in press led by Frankel's University of Texas colleague Dr. Alex Eastman shows CT's prowess in vertebral/carotid imaging, Frankel said. The researchers compared multislice CTA with conventional arteriography in 135 patients. With a 0.7% incidence of blunt carotid vertebral injuries (BCVI) over the study period, MDCT identified 43 injuries in 41 patients, and missed only a single grade I vertebral artery injury, while successfully grading lesions.

Spine imaging can probably be avoided altogether in awake and alert patients who have no distracting injuries, she said. If it is determined that imaging is needed, CT scanning should include obtunded patients. And CTA is sufficient to exclude carotid vertebral artery injury, she said.

"We probably don't need anything more than CT for neurologic injuries alone," Frankel concluded. "In head CT our (GCS) 3-13s, and probably our 14s should go to the scanner immediately; select patients with GCS 15 may not require head CT. I challenge you all to talk your neurosurgeons into doing that -- we certainly haven't been successful there."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

January 12, 2006

Related Reading

MDCT spurs boom in ER CT utilization, January 4, 2006

Massachusetts insurers seek to cut imaging utilization, September 12, 2005

MedPAC, Medicare, and imaging growth, August 16, 2005

When x-ray finds cervical spine injuries, CT picks up more, September 14, 2005

Copyright © 2006 AuntMinnie.com