In July 2001, the American Society of Radiologic Technologists (ASRT) launched a campaign to recruit minorities into the profession by creating the Royce Osborn Minority Student Scholarship. The scholarship is intended for entry-level students and pays tribute to Royce Osborn Sr., a generous, smiling man and World War II veteran who prevailed over racial prejudice to become a leader in his profession.

In an industry where high-tech equipment captures attention and dollars, Osborn, who died in 1997 at age 71, most valued the technologists he learned from and mentored.

"After all, radiology is more than just machines," Osborn said in a 1988 Inside Radiology article. By assisting quality students, the scholarship highlights Osborn’s emphasis on the field’s human potential. It also acknowledges the struggle of African-American radiology technicians during the civil rights era.

"In order to provide the best-quality healthcare, we feel really strongly that the workforce should reflect the patient population," said Ceela McElveny, ASRT director of public relations. Citing American Medical Association statistics, she said only 15% of the students enrolled in radiology programs in the U.S. are minorities, while the 2000 Census reveals that minorities (including Hispanic whites) comprise 29% of the U.S. population.

Osborn’s leadership qualities and experience at segregated hospitals during the civil rights era in the Deep South made him the obvious namesake for this new scholarship. In 1969, he became the first African-American president of the ASRT.

Colleagues and family describe Osborn as a pioneer and mentor throughout his 45-year career. Although he encountered racial prejudice and segregation, Osborn’s wife Paula says he was a fun-loving man who literally danced six months after a car accident took his right leg.

|

Osborn's son, Alton Osborn, 37, recalled residents boycotting the family’s ice cream parlor in North Carolina when they learned the owners were black. Mrs. Osborn recalled difficulty enrolling her children in a preferred, yet still segregated, Catholic school in New Orleans in the late 1950s. In addition to these family tribulations, Osborn’s career suffered from the effects of racial prejudice.

Passionate about his profession

Born in Algiers, LA, Osborn received a bachelor’s degree in biology from Xavier University in New Orleans, and medical technology training at Massachusetts Memorial Hospital in Boston. He started his career in 1952 as staff technologist for the U.S. Army Hospital in Ft. Polk, LA.

Despite the 1954 Supreme Court ruling shattering the "separate but equal" system in the South, southern hospitals remained segregated. In 1955, Osborn became chief RT at the Flint-Goodridge Hospital in New Orleans, widely acknowledged as the premier southern black hospital.

The hospital provided important healthcare to the city’s African-American population. Radiologic services at the time included routine x-rays, upper GI series, and barium enemas. It was the only private, noncharitable hospital in the city that allowed black physicians to practice medicine. The hospital closed in 1985, and in 1990, after years of neglect and vandalism, the building re-opened as a low-income apartment complex for the elderly.

|

James Eaglin, a retired radiology supervisor, started his career at Flint-Goodridge when Osborn was chief RT.

"He was a very good person to work with. He was very knowledgeable, and he transferred that knowledge to me," Eaglin said. Osborn was an innovative technologist who understood the science behind the equipment well enough to improvise machines when necessary and to improve on old designs. Eaglin credited Osborn with the development of a reciprocating bucky when stationary grids were the norm.

In the 1950s, Osborn and Eaglin joined the national ASRT after being denied membership in the segregated local organization. They nearly became the last members as well: Osborn halted an ASRT proposal that would have required membership in local chapters. If it had passed, he and other black technologists in the South would have been ineligible for national membership. They also were the first black technologists to register with the American Registry of Radiologic Technologists.

"We were not just coworkers. We were friends, good friends," said Eaglin, who as a young single man joined the Osborns for dinner most evenings before heading to night school.

When Osborn became ASRT president in 1969, he moved to Illinois, near the society’s home office, and took a job as chief x-ray technologist at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood. At Loyola, Osborn hired a visually impaired couple to work in the hospital’s darkroom. Paula Osborn likes to tell this story because years after Royce’s death, the daughter of that couple tracked down the Osborns to invite Royce to her parent’s 50th wedding anniversary.

As ASRT president, Osborn fought for professional licensing requirements to upgrade the status of RTs, an effort that continues today. Osborn supported higher standards of professional training and safety requirements. He also closely followed professional issues under debate in the U.S. government and within the ASRT itself, including universal position descriptions, federal licensure proposals, and minimum performance standards.

"He instilled pride in what you’re doing. He was fun to be around because he believed in what he was doing and you wanted to be a part of that," said Joan Parsons, ASRT vice president. "I think that’s why I remember him. He was so passionate about this profession."

Fostering change

While he earned professional accolades from the radiology community, Osborn took a hiatus in the 1970s. Paula Osborn said her husband was disillusioned that the few women and minority technologists working at the time were generally paid less than their white male counterparts.

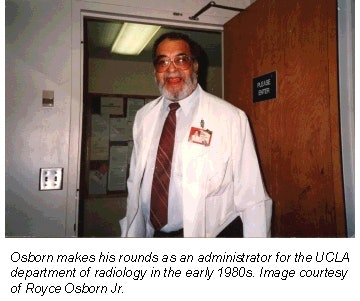

But after three years as a pharmaceutical sales representative for the Northern Ohio territory, Osborn returned to radiology. In 1977, he moved to California to become the radiology administrator at Brotman Memorial Hospital in Culver City, CA. His last stop before retirement was UCLA’s Center for the Health Sciences where he served as assistant to the diagnostic division chief for the department of radiological sciences.

|

Another competitive scholarship named for Royce and Paula Osborn provides funding for members of the American Healthcare Radiology Administrators to attend the organization’s annual meeting. In 1984, Osborn was the second recipient of the AHRA’s highest honor, the Gold Award. He authored A Professional Approach to Radiology Administration, called "the book on radiology administration" in a 1997 AHRA newsletter.

Paula Osborn said his administrative success came from the respectful way he treated the staff. "Royce believed that you get people to do things by praising the work that they do."

Asked what her husband might have thought of being the namesake to what is likely the industry’s first minority student scholarship, she said, "He didn’t think about being the first African-American anything. He was just proud of his accomplishments."

By Johnelle C. LamarqueAuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 8, 2001

Related Reading

ASRT accepting applications for minority scholarships, June 15, 2001

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com