The Netherlands started screening for breast cancer 30 years ago. During this period, we have learned a lot about the benefits and harms of breast cancer screening, and, therefore, we constantly adjust the Dutch program to optimize it as much as possible. This optimization has resulted in a mortality reduction of 50% for women who do attend all screening rounds between the ages of 50 and 75 in a biannual setting

We have developed a philosophy about the organization and maintenance of a screening program, based upon six pillars:

1. Think of screening like a medical chain

In this chain, equipment, technicians, and radiologists are the key players. It is as weak as the weakest link. Therefore, before starting a screening program, all three links have to be secured. In practice, this means that an adequate educational program and also a system for quality control have to be implemented before starting the actual screening process itself. It is a misperception that starting a screening program is equivalent to buying equipment.

Dr. Ruud Pijnappel, PhD. Image courtesy of EUSOBI.

Dr. Ruud Pijnappel, PhD. Image courtesy of EUSOBI.2. Discriminate between clinical breast radiology and screening for breast cancer

The mindset in a screening environment differs from a clinical setting. In screening, you only have to depict lesions with a high probability for breast cancer. All other lesions are not of interest in a screening setting. This requires additional training in a theoretical setting, but even more it requires specific skills. Therefore, in our opinion, a radiologist is not a screening radiologist unless these specific skills have been trained. In the Netherlands, it is obligatory to pass additional training before you are allowed to work in the Dutch national screening program. The additional training is also obligatory for technicians.

3. In addition to the certification of professionals, all equipment must be certified

This is the third pillar of our system. Certifying new mammography equipment before installation, weekly calibration of every mammography unit, and extensive testing every six months are part of our quality control system.

4. Recognition of the importance of auditing

To maintain the highest quality possible and to take account of the individual performance of technicians and radiologists, audits are essential, and this is another important pillar of our philosophy. During these audits, which take place once every three years, we benchmark the results from screening units all over the country. This gives insight into the regional performance in comparison to the national performance. In the audits, we arrange peer-to-peer discussions between the auditing team and the screening unit, which is also audited.

In this way, we have created a system in which scientific discussion forms the basis of adjusting the program instead of signing out of a list of items. The combination of benchmark and peer-to-peer discussions makes fine-tuning a real option in the Dutch screening program.

5. Full consideration of the recall rate

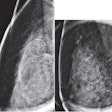

Another important element of our quality system is the recall rate. When we started screening, we thought that a recall rate of 1% would be optimal for the Dutch program.

The advantages of this low recall rate were a high positive predictive value (this means that relatively few women were recalled for a benign lesion) while detecting a lot of breast cancers at an early stage. After evaluating this recall rate by means of "the optimization study," published by the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2005, we changed our policy and went up to a recall rate of 2.4%. This is still very low compared with other countries, especially the U.S., but with the same breast cancer detection as in other countries (6.8 per 1,000).

We pay a lot of attention to recall rate in the Netherlands. Recall rate reflects, in essence, the balance between benefits and harms of a screening program. The more you recall, the more false positives (i.e., a woman recalled from the screening program but no malignancy after assessment) you will have. False-positive recalls should be avoided as much as possible because they constitute a serious drawback of screening without compensatory benefit for the affected subgroup of participants. In studies performed in the Netherlands, we discovered a drop in reattendance after a positive recall as high as up to 30%. Anxiety and discomfort for women, as well as high costs for the community (additional imaging and image-guided interventions), makes false positives a serious item to evaluate, educate, and control. Defining a recall rate and teaching and training radiologists form the backbone to minimize harms in a screening program.

6. Rigorous approach to data management

The last pillar is about data. Data are essential in a screening program -- not only information regarding incidence in relation to age, but also recall rate, detection of breast cancer, interval cancers (symptomatic cancers that appear between screening rounds), and stage of detection, and, in the long run, figures for survival are essential to evaluate and adjust the program. In the Netherlands, we have central storage of all mammography images produced during screening. But we also have a unique custom-made reporting system. Besides that, all pathology reports, not just breast, and data regarding all cancer types from all over the country are stored centrally. Coupling of these databases makes it possible to evaluate the Dutch screening program on a national level. This gives us the opportunity to calculate other items such as overdiagnosis.

Overall, our philosophy that screening differs from clinical breast radiology also accounts for the women involved. Therefore, screening in the Netherlands is arranged completely outside the hospital setting. We have 58 trucks with mammography equipment driving throughout the country to facilitate women having their mammography once every two years (paid for by the government) close to their home, avoiding a clinical setting. Apart from the 58 trucks, we have 20 stationary systems outside hospitals. This concept is accepted very well and is reflected in a constant high attendance rate of around 80%. Only in cases of recall and further assessment are women confronted with a hospital setting.

In conclusion, screening for breast cancer works, but it requires a solid infrastructure, consisting of education, monitoring, auditing, and continuous adjustment. The Dutch model reflects a comprehensive system resulting in a serious reduction of breast cancer mortality. Often the Dutch Expert Centre for Screening (LRCB) is consulted by countries that want to start or set up a screening program. Adjustment for local and cultural backgrounds is essential for making the program successful. But regardless, the country or cultural background, education is the key to success.

Dr. Ruud Pijnappel, PhD, is the secretary general of the European Society of Breast Imaging (EUSOBI) and a breast radiologist at the University Medical Centre Utrecht and the Dutch Expert Centre for Screening (LRCB) in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Editor's note: This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in the second edition of the Arab Health 2019 daily newspaper, published on 29 January. Pijnappel was due to speak about "Digital breast tomosynthesis in population-based screening programs" on 29 January as part of the Total Radiology conference at Arab Health 2019.