Using functional MRI (fMRI) and measurements of skin conductance, researchers have found that combat veterans with severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have distinct patterns in how their brains and bodies respond to danger and safety. These brain biomarkers could help identify those at risk of severe PTSD.

The study could explain why PTSD symptoms can be severe for some people but not for others, according to a team of researchers led by Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, PhD, of Yale University in New Haven, CT, and Daniela Schiller, PhD, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. They shared their results in an article published online on January 21 in Nature Neuroscience.

"This study clarifies that those who have the most severe symptoms may appear behaviorally similar to those with less severe symptoms but are responding to cues in subtly different, but profound, ways," said Susan Borja, PhD, chief of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Dimensional Traumatic Stress Research Program, in a statement. The NIMH, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), contributed funding for the study.

Harpaz-Rotem, Schiller, and colleagues had sought to examine how the mental adjustments performed during learning -- and how the brain tracks these adjustments -- relate to the severity of PTSD symptoms. They asked combat veterans with varying levels of PTSD symptoms to complete a reversal learning task that paired two mildly angry human faces with a mildly aversive stimulus. In this first phase, the participants learned to associate one face with the mildly aversive stimulus. This association was reversed in the second phase of this learning task; participants then learned to associate the second face with the mildly aversive stimulus.

All participants were able to accomplish this reversal learning task. However, the researchers found that highly symptomatic veterans responded with greater conductions in their physical arousal -- skin conductance responses -- and in several brain regions to cues that did not predict what they had expected.

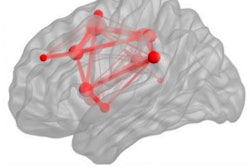

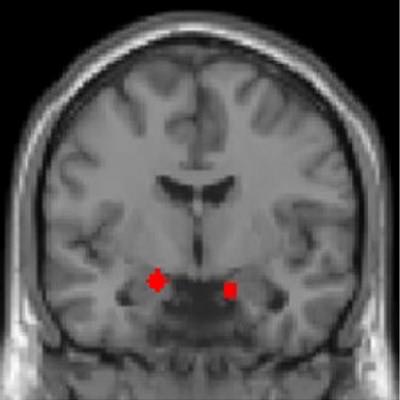

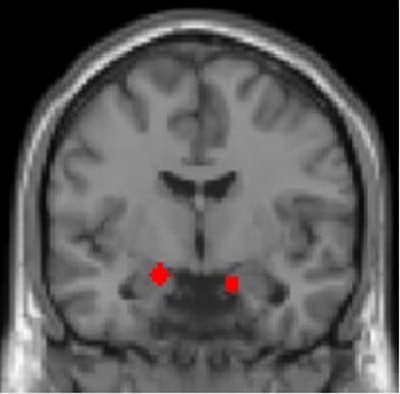

The researchers used fMRI to find that both smaller amygdala volume and responses to face stimuli in the amygdala independently predicted the severity of PTSD symptoms. What's more, the group also discovered differences in other brain regions involved in response to threat learning, such as the striatum, hippocampus, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex.

Functional MRI of combat veterans showed that the amygdala -- defined functionally in red -- is a particularly important area of the brain for predicting severity of PTSD symptoms. Image courtesy of Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, PhD; Daniela Schiller, PhD; and Nature Neuroscience.

Functional MRI of combat veterans showed that the amygdala -- defined functionally in red -- is a particularly important area of the brain for predicting severity of PTSD symptoms. Image courtesy of Ilan Harpaz-Rotem, PhD; Daniela Schiller, PhD; and Nature Neuroscience."What these results tell us is that PTSD symptom severity is reflected in how combat veterans respond to negative surprises in the environment -- when predicted outcomes are not as expected -- and the way in which the brain is attuned to these stimuli is different," said Schiller in a statement from the NIH. "This gives us a more fine-grained understanding of how learning processes may go awry in the aftermath of combat trauma and provides more specific targets for treatment."

The inability to adequately adjust expectations for potentially aversive outcomes has potential clinical relevance as this deficit may lead to avoidance and depressive behavior, Harpaz-Rotem noted.