Getting an MRI scan won't help you lose weight, but the modality can be useful in determining the success of bariatric surgery in combination with a very low-calorie diet. A specialized MRI sequence helped track the success of bariatric surgery in a study published online December 18 in Radiology.

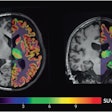

The approach is known as quantitative chemical shift-encoded (CSE) MRI, which is designed to calculate liver fat concentration by measuring proton density fat fraction (PDFF). PDFF provides liver fat as a percentage, which gives clinicians and patients an indication of obesity. Performing CSE MRI scans before and after surgery and dietary changes can provide a barometer of patients' progress toward a leaner, healthier existence.

"In addition to demonstrating the clinical utility and feasibility that CSE MRI provides in the monitoring of hepatic PDFF over time, our analysis provided a number of insights into reductions in liver fat content following bariatric surgery," wrote lead author Dr. Dustin Pooler and colleagues from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Obesity epidemic

It is estimated that as many as two-thirds of adults in the U.S. are overweight or obese. This unhealthy trend has led to an increase in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which can lead to hepatic steatosis and cirrhosis of the liver, as well as an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma.

One effective liver fat reduction method is bariatric surgery, which can result in weight loss and also improve other health issues.

The problem is that the connection between weight loss, bariatric surgery, and reduced liver fat is "not well understood," Pooler and colleagues wrote, and there is a lack of "reproducible, noninvasive methods to quantify liver fat."

Of the available diagnostic options, liver biopsy has been the reference standard for liver fat quantification, but it is invasive. Even noninvasive imaging modalities such as MRI, MR spectroscopy, and ultrasound are "of limited utility due to poor accuracy or technical difficulty," the researchers wrote.

Meanwhile, CSE MRI has been validated in several studies for its ability to assess liver fat in cases of hepatic steatosis and in patients with morbid obesity. Hence, the researchers sought to explore the use of CSE MRI to quantify proton density fat fraction as a biomarker of liver fat concentration before and after bariatric surgery and to compare changes in PDFF against other anthropometrics, namely body mass index (BMI), weight, and waist circumference.

On the scale

From June 2010 through May 2015, Pooler and colleagues prospectively enrolled 43 women (mean age, 50.8 years; range, 27-70 years) and seven men (mean age, 51.7 years; range, 36-62 years) with severe obesity who were scheduled to undergo surgical evaluation for bariatric surgery. They also were about to participate in a preoperative low-calorie diet of 600 to 900 calories per day.

The subjects underwent a baseline MRI scan two to three weeks before surgery to determine an initial proton density fat fraction for liver fat concentration. At that time, the researchers also recorded the subjects' BMI, weight, and waist circumference. A second preoperative MRI scan was performed one to three days before bariatric surgery, with a repeat of BMI, weight, and waist circumference measurements.

After bariatric surgery, the patients again underwent MRI scans with CSE at one month, three months, and six to 10 months to quantify changes in PDFF. Once again BMI, weight, and waist circumference were measured at each time point. All MRI scans were performed on 1.5-tesla or 3-tesla systems (Signa HDxt 1.5T and 3.0T, Discovery MR750 3.0T, and Optima MR450w 1.5T, GE Healthcare).

Less is more

By the end of the study, the researchers recorded statistically significant differences in proton density fat fraction, BMI, weight, and waist lines collectively among the 50 patients. Most importantly, CSE MRI showed an average liver PDFF of 4.9% at the final scan six to 10 months after surgery, which is within normal limits (normal PDFF is less than 5%). In addition, the mean time to reach that standard PDFF level was approximately five months.

| Correlation of PDFF on MRI scans with measures of patient obesity | |||

| Baseline MRI | Final MRI | p-value | |

| Liver PDFF | 18.1% | 4.9% | < 0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 44.9 | 34.5 | < 0.0001 |

| Weight (kg) | 121.5 | 91.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 132.2 | 110.9 | < 0.0001 |

The study results showed a rapid early phase of improvement in liver fat, followed by a phase of continued reductions at a slower pace with each succeeding CSE MRI scan and measurement of PDFF and other anthropometrics, Pooler and colleagues noted. Those changes began with the initiation of the low-calorie diet and occurred in advance of the overall improvements in BMI among the patients.

In other findings, the only strong predictor of change in proton density fat fraction was the level at baseline. In other words, a greater level of PDFF at baseline was an indicator of a "more rapid decrease" in PDFF by the time of the final CSE measurement, according to the researchers.

The results "have possible patient care implications, as bariatric patients with marked hepatic steatosis may see substantial improvement in liver PDFF regardless of starting anthropometrics or degree of weight loss following surgery," they concluded. "Consequently, it may be reasonable to consider the severity of hepatic steatosis -- independent of weight or BMI -- when deciding to enroll a patient for bariatric surgery."