The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has reaffirmed its prior decision to recommend against imaging-based screening for pancreatic cancer in asymptomatic individuals, in a recommendation statement published online August 6 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

By giving pancreatic cancer screening a D grade, the task force has determined with moderate to high certainty that the potential harms associated with pancreatic screening outweigh its benefits. The latest reaffirmation recommendation statement is based on an evidence report and systematic review conducted by Nora Henrikson, PhD, from Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle and colleagues from various U.S. institutions.

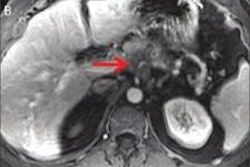

The most widely used imaging modalities for pancreatic cancer screening -- ultrasound, CT, MRI -- and biomarkers from blood tests have not been found to be accurate in the detection of pancreatic cancer at an early enough stage to be beneficial to patients, USPSTF member Dr. Chyke Doubeni from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, said in an interview with JAMA.

"If you had an effective screening test that could detect the cancer early, and we had treatments that were effective for treating early conditions that could prevent death, then you have a good scenario in which screening can be helpful in this devastating condition," he said. "But we have a ways to go until we can get treatments that are really effective and have fewer harms than is the case for current treatment modalities."

Dearth of evidence

Pancreatic cancer is the third most common cause of cancer death in the U.S. and is projected to overtake colorectal cancer as the second leading cause of death by 2030. Identifying populations at the highest risk of pancreatic cancer is critical, yet an adequate screening exam for the disease remains wanting, Henrikson and colleagues noted.

In 2004, the USPSTF considered the possible benefits of pancreatic cancer screening but found sparse evidence demonstrating the viability of any test -- ultimately giving the service a D grade.

Returning to the topic 15 years later, the USPSTF enlisted Henrikson and colleagues to review all relevant abstracts and articles listed in the Medline and PubMed databases, as well as in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, from January 2002 to April 2018. They identified and analyzed the results of 13 prospective screening studies that met their standards for quality research. The studies covered 1,317 individuals who underwent screening for pancreatic adenocarcinoma on ultrasound, MRI, and/or CT (JAMA, August 6, 2019).

The researchers centered their review of pancreatic cancer screening on several key matters: the effect of screening and treatment on health outcomes, the diagnostic accuracy of screening, and the potential harms of screening and treatment.

They found that the collective imaging exams had uncovered 18 cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 1,156 high-risk individuals and zero cases of cancer in 161 average-risk individuals. Diagnostic yield for pancreatic adenocarcinoma ranged from 0% to 7.5% in the studies.

Among all studies, the researchers determined that not a single paper had investigated the effect of screening on the participants' morbidity or mortality, or on the effectiveness of treating pancreatic cancers detected on the screening exams. In contrast, many of the studies reported instances of procedural and surgical harms -- albeit mild and inconsistent -- associated with screening and subsequent treatment.

"Collectively, the included studies suggest that imaging-based screening in populations at increased familial risk can identify pancreatic adenocarcinoma and may result in stage shift toward earlier stage at detection. ... However, in the absence of longer-term follow-up data, it is unclear if the available evidence represents a true clinical benefit," the authors concluded.

Reasons for optimism

The USPSTF thus concluded that the harms of screening for pancreatic cancer exceed any potential benefits and found no new substantial evidence that would change its previous statement recommending against screening in asymptomatic adults.

In light of the statement, Dr. Ralph Hruban from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Dr. Keith Lillemoe from Massachusetts General Hospital discussed several barriers restricting the early diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer in an accompanying editorial:

- Individuals are most likely to present with symptoms at advanced stages of cancer due to the tendency of the cancer to progress rapidly and invade the veins, leaving only a narrow window (a year and a half, on average) for early detection. The pancreas is located in the rear of the abdomen and relatively inaccessible.

- Current imaging technology is limited in its capacity to distinguish between early-stage cancers that require surgical treatment and low-grade precursors that only need surveillance. As such, screening is likely to generate a high rate of false positives that could alarm patients and possibly lead to unnecessary surgical intervention, even for tests with a specificity as excellent as 99%.

- Surgery for pancreatic cancer is complex and often fraught with potential complications.

Despite these hurdles, "one can easily imagine the day in which high-risk individuals will be screened using new molecular-based technologies ... [and] all abdominal imaging will be scanned using deep learning and other approaches to identify subtle changes in the pancreas," Hruban and Lillemoe wrote.

"We are optimistic," they continued. "Although the student may be getting a grade of D, this student deserves an A for effort, and we see a most improved award on the near horizon."

New opportunity for medicine

Along those lines, Dr. Anne Marie Lennon, PhD, and colleagues from Johns Hopkins University offered several strategies to address the many challenges facing pancreatic cancer screening in an additional editorial:

- Continue improving the characterization of the three precursor lesions that lead to pancreatic cancer: pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), and mucinous cystic neoplasms. The latter two, but not the first, are easily identified on CT.

- Pinpoint the ideal period of time for screening. For example, there appears to be a three- to five-year window between the early detection of IPMN and its progression to invasive cancer.

- Consider combining imaging with other modes of screening such as DNA blood tests and cyst fluid tests, which have proved capable of distinguishing between precursors and invasive cancer in early cases.

- Discover ways to use deep learning and radiomics to help radiologists spot incidental pancreatic lesions on abdominal MRI and CT scans.

- Focus on identifying high-risk individuals, including those with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer (at least two family members), certain confirmed genetic mutations, and older individuals with new-onset diabetes.

Future studies should evaluate whether integrating risk factors into recommendations helps identify individuals with a high disease prevalence who would benefit most from screening, Lennon and colleagues wrote.

"Although the challenges of effective screening for pancreatic cancer are also daunting, they offer another opportunity for medicine to overcome adversity and to make another vision a reality," they concluded.