Using MRI, researchers have found that chronic inflammation measured by a biomarker in the blood of middle- to late-age adults could be linked to visible white-matter damage in the brain and related poor cognition and dementia, according to a study in the August issue of Neurobiology of Aging.

The results suggest "to us that inflammation may have to be chronic, rather than temporary, to have an adverse effect on important aspects of the brain's structure necessary for cognitive function," said lead author Keenan Walker, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of neurology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in a statement from the university.

Based on the findings, drugs or lifestyle changes implemented at midlife or earlier to control inflammation could be important for delaying or preventing cognitive decline in old age, according to the group.

Walker and colleagues analyzed brain structure and integrity for more than 1,500 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. They also examined a marker of inflammation over a 21-year period, extending from middle age to late life. Each adult made five visits with study coordinators at an average of one every three years (Neurobiol Aging, August 2018, Vol. 68, pp. 26-33).

MRI scans were performed on the final visit to look for evidence of white-matter damage. The researchers also took blood samples at three visits to measure for high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, a standard indicator of inflammation. Subjects with at least 3 mg/L of C-reactive protein were considered to have elevated inflammation.

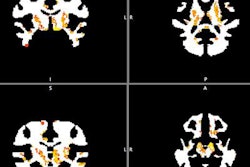

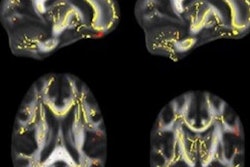

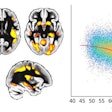

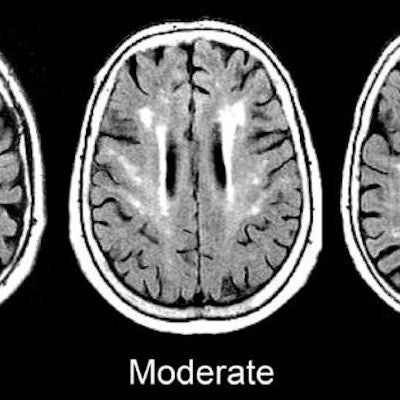

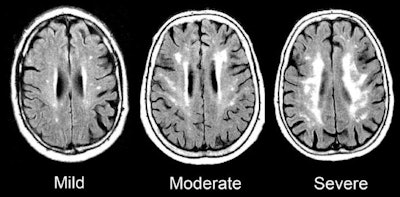

MRI scans show damage to the brain's white matter. Images courtesy of the Gottesman Lab.

MRI scans show damage to the brain's white matter. Images courtesy of the Gottesman Lab.Overall, increasing and chronic inflammation were associated with the most damage to white matter; therefore, there is reason to infer a cause and effect relationship between growing and persistent inflammation and evidence of dementia, according to Walker. The researchers stopped short of saying their results were conclusive, however.

"Our work is important because currently there aren't treatments for neurodegenerative diseases, and inflammation may be a reversible factor to prolong or prevent disease onset," added senior author Dr. Rebecca Gottesman, PhD, a professor of neurology and epidemiology. "Now, researchers have to look at how we might reduce inflammation to reduce cognitive decline and neurodegeneration."