Eye-tracking technology has the potential to monitor the progress of trainee anesthesiologists as they improve their expertise in interpreting ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia images, according to a study in the February issue of the Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine.

The research suggests there could be a more objective tool for evaluating learning in the area of ultrasound-guided anesthesia, rather than subjective measures such as self-assessment, multiple-choice tests, checklists, or rating scales, wrote the team led by Dr. Lindsay Borg from Stanford University.

"Many of these tools are labor-intensive to implement, rely on subjective ratings, and, importantly, do not explore visual processing, a key aspect of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia," the group wrote. "For procedural and visual-based tasks, eye tracking holds great promise as a tool for monitoring training progress toward the development of expertise."

Gauging gaze

Eye tracking measures visual patterns by recording the direction of a user's gaze and its relationship to an area of interest (AOI). Gaze patterns captured by eye-tracking technology do not necessarily reflect a user's understanding of what he or she is seeing, but comparing patterns between expert and novice readers can help researchers develop appropriate skill training (J Ultrasound Med, February 2018, Vol. 37:2, pp. 329-336).

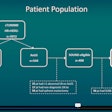

Borg and colleagues sought to apply eye-tracking technology specifically to the field of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia, exploring the feasibility of using it to quantify the expertise of readers and test the hypothesis that eye tracking could distinguish experts from novices. Five novice anesthesiology residents and five anesthesiology experts participated in the study between October and December 2016.

Each reader was given eye-tracking glasses (Tobii, Karlsrovägen, Sweden). The glasses use corneal reflection to determine the focus of a person's gaze. The glasses were calibrated to each study participant by having the person focus on a black-and-white target at arm's distance while wearing the glasses.

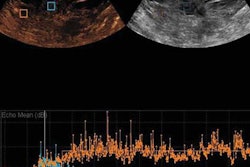

Readers viewed five static sonograms of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia. They then responded to anatomy-based questions related to each of the images while their eye movements were recorded; participants answered the question by pointing a handheld laser to their selected area on the screen. The answer to each question was a specific location on the sonogram (the AOI).

The primary outcome was total gaze time in the AOI; secondary outcomes were total gaze time outside the AOI, total time to answer the question, and time to first fixation on the AOI.

Total gaze time in the AOI did not differ between the two groups (seven seconds for each). But gaze time outside the area of interest was greater for novices than for experts (75 versus 44 seconds, p = 0.005). Time to first fixation on the AOI was shorter for the expert anesthesiologists, at 15 seconds, than the novices, at 25 seconds. Finally, total time to answer the question was 40 seconds for the experts versus 60 seconds for the novices.

"When qualitatively comparing the visual search pattern of experts and novices, the experts' gaze was quickly drawn to more anatomically relevant structures within the image," Borg and colleagues wrote. "Although the time spent in the [area of interest] was not different, novices spent more unfocused gaze time within irrelevant superficial tissues that experts ignored."

Better training?

This study is a first step toward validating eye tracking as an objective measure of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia skill, the researchers wrote. In addition, it demonstrates that expertise in this particular task translates to eliminating unfocused time by ignoring irrelevant ultrasound features and focusing on areas that provide useful clinical information.

"Experts spend less time gazing outside of the AOI compared to novices," the authors wrote.

The study findings suggest that eye tracking could help anesthesiology trainees develop expertise more quickly, Borg and colleagues concluded.

"Objective assessment of the differences in gaze patterns between novices and experts using eye tracking provides crucial feedback that may directly influence the process of training in ultrasound-guided anesthesia," they wrote. "Novices can be trained to gaze like an expert ... by studying an expert's gaze pattern during a task."