"With smoking the crack cocaine and the cigarettes, her lungs are all gunked up. There are nodules around the chest and dark marks," Mitch Winehouse said (Sunday Mirror, June 22, 2008).

But long before it made headlines with Amy Winehouse, crack lung was making news in clinical journals. AuntMinnie.com reviews the literature and describes the clinical and imaging manifestations of the condition and other common pulmonary complications from crack cocaine use.

Crack 101

Many people may think of cocaine as the powdered, hydrochloride salt form that can be snorted or dissolved in water and injected. Crack cocaine is cocaine that has not been neutralized by an acid to make the powder and instead comes in the form of rock crystal. It's smoked by heating and inhaling the vapors into the lungs, where absorption into the bloodstream is as rapid as by injection, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In 2006, 6 million people in the U.S. ages 12 and older reported using cocaine, with 1.5 million of them using crack cocaine at least once in the year prior to being surveyed, according to results of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Cocaine is the leading illicit substance for emergency department (ED) drug-related visits. In the past decade, cocaine-related ED visits have increased by more than 330%, based on reports by the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN). In 2005, U.S. hospitals had an estimated 108 million ED visits, with 1.4 million of these associated with drug misuse or abuse. Cocaine was involved in nearly one in three (31%) drug-related ED visits, according to the 2005 DAWN report. People age 34 and younger accounted for 41% of cocaine-related ED visits.

This past March, the American Heart Association (AHA) issued a scientific statement advising physicians to check for cocaine use in young patients with chest pain and those with no apparent heart disease risk factors (Circulation, March 2008, Vol. 117:14, pp. 1897-1907).

If a heart attack is suspected, cocaine use is important because the drug could affect treatment, according to Dr. James McCord of the Henry Ford Medical System in Detroit, chair of the AHA statement writing committee. Common heart attack treatments, such as clot-busting drugs and beta-blockers, can be dangerous with cocaine use, the AHA noted.

Crack lung makes headlines

While cocaine's cardiovascular effects and complications, such as heart attacks and strokes, are well-known, the pulmonary complications from smoking crack cocaine may not be as familiar -- particularly crack lung. The condition has been described as an acute pulmonary syndrome and an acute lung injury.

In 1987, physicians from Hutzel Hospital at Wayne State University in Detroit described a complication of cocaine abuse previously unreported, dubbing it "crack lung." A patient developed fever, transient pulmonary infiltrates, and bronchospasm in three separate episodes after inhaling cocaine, they stated. The condition was linked with eosinophilia, pruritus, and an elevated immunoglobulin E level (American Review of Respiratory Disease, November 1987, Vol. 136:5, pp. 1250-1252).

In August 1990, physicians from the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver reported on four patients who presented with crack lung after inhaling cocaine. Two of the patients had "prolonged inflammatory pulmonary injury associated with fever, hypoxemia, hemoptysis, respiratory failure, and diffuse alveolar infiltrates," the authors wrote (Am Rev Respir Dis, August 1990, Vol. 142:2, pp. 462-467).

Lung tissue samples from both patients revealed "diffuse alveolar damage, alveolar hemorrhage, and interstitial and intra-alveolar inflammatory cell infiltration notable for the prominence of eosinophils," the physicians wrote. The patients quickly improved after receiving systemic corticosteroids, they noted.

The other two patients "presented acutely with diffuse pulmonary alveolar infiltrates associated with dyspnea and hypoxemia" without fever, but their infiltrates and symptoms spontaneously resolved within 36 hours of discontinuing cocaine, the group wrote.

Other reported symptoms of crack cocaine use include chest pain, violent coughing, and wheezing, particularly with patients with a history of asthma.

These are your lungs on crack

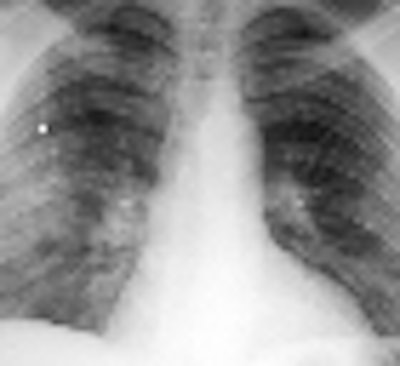

On x-rays, acute lung injury after cocaine use can appear as "bilateral, perihilar areas of increased opacity or attenuation, usually without pleural effusion or cardiomegaly," according to Dr. Michael Gotway and colleagues from San Francisco General Hospital; the University of California, San Francisco; and Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. "High-resolution CT may show multifocal ground-glass attenuation associated with septal thickening," but the condition clears up quickly after discontinuing cocaine use, they reported (RadioGraphics, October 2002, Vol. 22:4, pp. S119-S135).

|

| Acute lung injury (crack lung) in a 37-year-old man who presented with shortness of breath and cough after crack use. Above, frontal chest radiograph reveals ground-glass areas of increased opacity in the right lower lobe (arrow), a finding that is consistent with numerous causes, including edema, infection, hemorrhage, and aspiration. Below, high-resolution CT scan (level = -700 HU, window width = 1,000 HU) reveals ground-glass attenuation (arrows) with interlobular septal thickening (arrowheads). The differential diagnosis of these findings includes infection (especially Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia), lipoid pneumonia, and alveolar proteinosis, among numerous other causes. Bottom, frontal chest radiograph obtained two days after CT shows resolution of the increased opacity. Fig. 3a, b, c. Gotway MB, Marder SR, Hanks DK, et al. "Thoracic Complications of Illicit Drug Use: An Organ System Approach." RadioGraphics. 2002;222:S119-S135. |

|

|

Another complication of crack cocaine use is pulmonary hemorrhage. "At radiography, pulmonary hemorrhage manifests as multifocal bilateral areas of increased opacity with a normal heart size. Effusions are usually small or absent," Gotway and colleagues wrote. CT usually shows "multifocal ground-glass attenuation that is occasionally centrilobular in distribution and associated with interlobular septal thickening," they added. Pulmonary hemorrhage also clears quickly after stopping cocaine use.

"Because pulmonary hemorrhage and acute lung injury are radiographically indistinguishable, the development of respiratory failure with bilateral airspace areas of increased opacity that appear shortly after crack use and clear rapidly after cessation of drug use has been termed 'crack lung,' " the team wrote.

Crack complications

Other common complications of crack cocaine use include pulmonary edema, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum.

In 1989, Drs. Christopher Hoffman and Philip Goodman from San Francisco General Hospital reported on five patients with pulmonary edema who had smoked cocaine. No possible cause for the edema was found except for cocaine use, they noted. The chest radiographs showed "bilateral perihilar and fairly symmetric interstitial and/or alveolar infiltrates and a normal-size heart," they wrote (Radiology, August 1989, Vol. 172:2, pp. 463-465).

"In a young, otherwise healthy patient without known cardiopulmonary risk factors, the presence of pulmonary edema on a conventional chest radiograph should alert the radiologist to the possible diagnosis of cocaine smoking, especially if there is a history of drug abuse," they wrote. "Unless the possibility of cocaine smoking is raised, the radiographic changes may be falsely attributed to acute myocardial infarction or ... atypical pneumonia."

Image findings for cardiogenic pulmonary edema include cardiomegaly, peribronchovascular and interlobular septal thickening, and pleural effusions, as well as airspace areas of increased opacity that represent alveolar edema with a severe case, according to Gotway and colleagues. With CT, cardiogenic pulmonary edema presents as smooth interlobular septal thickening, pleural effusions, and ground-glass attenuation, they wrote.

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema has also been reported with crack cocaine use. "Radiographic findings are similar to those of other causes of pulmonary edema, most commonly taking the form of bilateral perihilar airspace opacification," wrote Dr. Ian Hagan of the Bristol Royal Infirmary and Dr. Kashif Burney of Southmead Hospital, both in Bristol, U.K. "In contrast to cardiogenic pulmonary edema, pleural effusion and cardiomegaly are usually absent.... Typically, radiographic abnormalities resolve rapidly -- often within hours" (RadioGraphics, July-August 2007, Vol. 27:4, pp. 919-940).

Pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum may result from the inhaling techniques of smoking cocaine. "Deep inhalation of the drug may be followed by a Valsalva maneuver and coughing, which may lead to alveolar rupture and subsequent dissection of air into the pleural space. Pneumothorax is usually unilateral but may, in rare cases, be bilateral," Gotway and colleagues noted. Hydropneumothorax may also develop if adjacent vasculature is damaged, they added.

Coughing after deeply inhaling the drug can cause "increased alveolar pressure and subsequent dissection of air into the pulmonary interstitium," resulting in pneumomediastinum and, rarely, pneumopericardium, they explained.

Other pulmonary complications of crack cocaine use include airway injury, asthma, eosinophilic lung disease, bronchiolitis, bronchiolitis obliterans with organized pneumonia, emphysema, infection and aspiration pneumonia, and tumors.

Cracking the case

The effects from smoking crack cocaine can also mimic pulmonary embolism, according to a 2004 case report. The authors described a patient with a history of inhaled cocaine use who presented with a "high clinical suspicion for pulmonary embolism and a high-probability ventilation-perfusion lung scan" (Clinical Nuclear Medicine, November 2004, Vol. 29:11, pp. 756-757).

But an angiogram showed no embolism, and the authors concluded that the syndrome was due to "intense pulmonary artery vasospasm secondary to cocaine inhalation." They noted that a pulmonary angiogram may be needed for correct diagnosis in such patients and to avoid unnecessary anticoagulation treatment.

Crack cocaine use has also been known to mimic sarcoidosis. Doctors from Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City first reported on this in a case study in 1999. They evaluated a 39-year-old patient with a history of frequent crack cocaine use who presented with progressive dyspnea. They found "bilateral interstitial pulmonary infiltrates and hilar adenopathy, diffuse pulmonary uptake of gallium, and markedly elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme activity" (American Journal of the Medical Sciences, June 1999, Vol. 317:6, pp. 416-418).

Interstitial and perivascular histiocytes containing refractile, polarizable material, which was presumed to have been inhaled with the cocaine, were found with open lung biopsy. "Paratracheal lymph nodes were enlarged, reactive, and contained similar polarizable material," the authors reported. However, the "well-formed, non-necrotizing granulomata characteristic of sarcoidosis were not present in either tissue specimen," they wrote.

Radiologists and crack

Because smoking crack cocaine doesn't leave telltale needle tracks like intravenous cocaine use, and patients may be reluctant to divulge their past drug use, physicians need to be aware of the pulmonary complications of crack cocaine to quickly and accurately diagnose patients and identify the appropriate treatment. Radiologists in particular need to be familiar with the complications and their imaging manifestations.

"For a large number of these complications, imaging plays a key role in their detection and characterization," Hagan and Burney wrote in their 2007 RadioGraphics paper. "The illicit nature of recreational drug use means that at the time a patient presents with a complication in either the acute or chronic setting, the underlying cause may not be known, and it is the reporting radiologist who may be the first to suggest the diagnosis."

By Heather Hokenson

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 3, 2008

Related Reading

Scientists pinpoint altered brain region in addicts, February 26, 2008

Prefrontal cortex disrupted by cocaine, impairing impulse control, October 18, 2006

Cocaine use linked to left ventricular dysfunction, May 4, 2006

Cocaine and stroke not just for the young and healthy, April 12, 2006

Cocaine's heart-damaging effects likely immediate, December 20, 2005

References

Barden JC. "Crack Smoking Seen as a Peril to Lungs." New York Times. December 24, 1989. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?&res=950DE6DB1E3AF937A15751C1A96F948260. Accessed June 27, 2008.

"Cocaine." National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. http://www.drugabuse.gov/drugpages/cocaine.html. Accessed June 27, 2008.

"Cocaine." U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Web site. https://www.dea.gov/pr/multimedia-library/publications/drug_of_abuse.pdf#page=47. Accessed June 23, 2016.

"Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2005: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits." Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. March 2007. http://dawninfo.samhsa.gov/files/DAWN-ED-2005-Web.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2008.

"Emergency Department Trends From the Drug Abuse Warning Network, Final Estimates 1995-2002." Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. August 2003. http://dawninfo.samhsa.gov/old_dawn/pubs_94_02/edpubs/2002final/files/EDTrendFinal02AllText.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2008.

Eurman DW, Potash HI, Eyler WR, Paganussi PJ, Beute GH. "Chest pain and dyspnea related to 'crack' cocaine smoking: Value of chest radiograph." Radiology. 1989;172(2):459-462.

Restrepo CS, Carrillo JA, Martí:nez S, Ojeda P, Rivera AL, Hatta A. "Pulmonary complications from cocaine and cocaine-based substances: Imaging manifestations." RadioGraphics. 2007;27(4):941-956.

"Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings." Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. September 2007. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k6nsduh/2k6Results.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2008.

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com